CHAPTER 1

The House that Modern Medicine Built

“Each generation must examine and think through again, from its own distinct vantage point, the ideas that have shaped its understanding of the world.”

Richard Tarnas, The Passion of the Western Mind, 1991

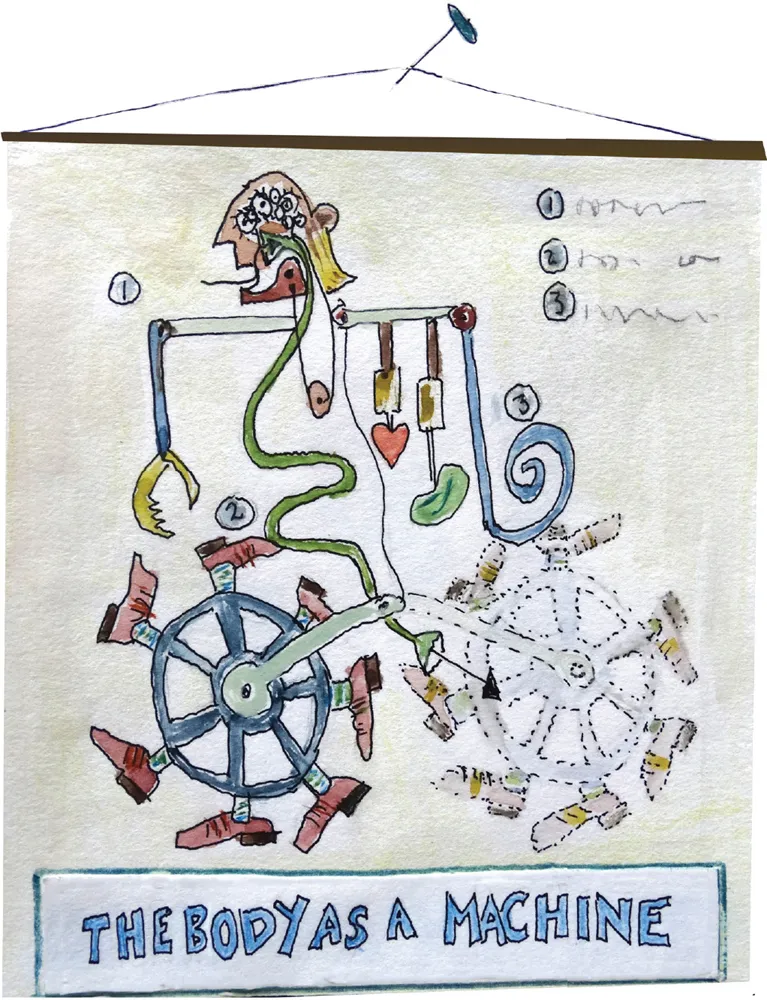

Modern medicine has built its success on a deep understanding of the body as a machine. It is this understanding that has determined both the fundamental nature of the encounter between doctor and patient and the vast infrastructure of complex healthcare systems that has grown up to serve it. It is beguilingly simple: take a history from the sick person, seek out specific details which cover a range of pre-existing disease states, physically examine the body (or mentally examine the mind), come to a conclusion about what is wrong and fix it. With advances in drug and surgical treatments in the last century, especially for infections and traumatic injuries as well as problems with worn-out parts, this approach has been hugely successful, and has transformed the odds of us all living to a ripe old age.

This progress has been hard won. Understanding the body as a machine required a radical breakthrough in thinking centuries ago, derived from an early interest in anatomy. Whilst this can be traced to ancient Egypt and Greece, the modern objective exploration of the body began in earnest in the 16th and 17th centuries. The early pioneers of modern medicine used dissection of the human body as a fundamental source of knowledge. Vesalius is often regarded as its founder although we now know that Leonardo da Vinci undertook many dissections but did not publish his drawings in his lifetime.

In his treatise De humani corporis fabrica (1543) Vesalius challenged the previous orthodoxy based on Galen’s work in the 2nd century – that our health is the result of an imbalance in humours (black and yellow bile, blood and phlegm). Vesalius’s book, in seven volumes, was lavishly illustrated with detailed diagrams of the key structures of the human body – heart, lungs, liver, gut, arteries, veins, bones and muscle. As David Armstrong has described, in this way the body became legible through a new language of structure and description, based on the objective evidence of human dissection1.

Early modern doctors learned to read the body through anatomical eyes and, in doing so, were starting to see the body as object rather than subject, to ‘objectify’ their gaze. This shift created a distance between the experience of inhabiting the body and its external description. The first is unique to every person, connecting to their family, community and life in its widest sense. The latter is de-contextualised, focusing on structures and function at the same time, opening up the possibility of new understandings about how the body works. Thus William Harvey was able to describe the circulation of the blood for the first time in 1628, not just describing the structure of arteries and veins but likening the flow of blood through the heart to that of liquid through a mechanical pump. This discovery had the interesting corollary of making the King’s heart no different from those of his subjects. Some argue this shift in worldview made it easier for the rise of democracy and an end to the divine right of Kings2.

In time, doctors came to identify this anatomical, mechanical map of the body as the actual territory rather than just one of many possible representations. Similarly, doctors began to cluster symptoms and signs in the patients who came to them and labeled them as ‘diseases’, giving them specific names.

In order to develop this systematic knowledge and understanding of medicine, students started to learn from lectures and textbooks, dissection of corpses, and the hands-on examination of patients who were being treated in teaching hospitals. These establishments became big, powerful institutions, attracting the best medical men (it was all men for over a century) to teach in them. Doctors in turn gained reputations, which allowed them to charge high fees for their private practice.

The training of doctors along these lines socialised them into seeing illness and suffering in a particular way and created a distance between them and the lived experience of their patients. This led to the emergence of what Michel Foucault described as the “clinical gaze”3. It means seeing people as bundles of symptoms or data or diagnoses rather than as themselves. The clinical gaze might be detected in the kind of conversation that can happen between doctors when they refer to a sick person on a ward as “the lymphoma in the corner”. I found myself caught up in this world when I was practising hospital medicine. Even the persistence of the word ‘patient’ for a person experiencing illness is a manifestation of the passivity of the role compared with the active role of diagnosis and treatment by the doctor.

The clinical gaze is not just about the way doctors view patients. It represents a whole worldview which defines roles, relationships, what knowledge is taken seriously, and what is not, how power is exercised and how healthcare is organised. The process is sub-conscious, not a conspiracy, but it leads to a clear demarcation of roles in modern healthcare.

Medical knowledge and skill are highly prized and protected as a scare resource and doctors remain well-paid professionals. Nurses have attempted to emulate that success by becoming a graduate–level entry profession, codifying their knowledge and skills in the same way. Other healthcare professionals have followed suit, each group with its own training and professional organisation.

With advances in psychology and sociology in the 1960s and 1970s, this bio-mechanical model of disease was criticised for failing to take into account the wider circumstances in people’s lives, which have both an impact on the development of disease and implications for how it might be treated. Most medical schools today teach the ‘bio-psycho-social’ model of disease, which incorporates psychological and social influences when making a diagnosis.

However, despite these adjustments, doctors still locate the pathology of disease in individual patients and remedies still focus on physical or behavioural levels of intervention. Clearly, psychiatry is different – recognising that a person with a disordered mind needs psychological and social support often over many years. However, even here, the prevailing view is that psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and bi-polar disorder are largely the consequence of chemical imbalances in the brain.

Production-line healthcare

Today’s medicine is largely practised within multi-disciplinary teams comprising many different professionals. In theory this opens up the opportunity for a more integrated view of disease and treatment. For example, a stroke unit may have doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, speech and language therapists, occupational therapists and psychologists working together for the optimal treatment of people who have had strokes. However, the knowledge and skills of each professional group do not fundamentally change the clinical gaze — they each simply fill in further detail. The disease is still located in the individual and the treatment is largely co-ordinated around them.

Because so many professional perspectives are needed to treat health problems today many conditions now have to be managed through specific ‘care pathways’, akin to production lines in manufacturing. Once someone is admitted with a stroke, for example, they receive input from a variety of different professionals at specified times in the course of their treatment and recovery. This pattern of care has been called ‘integrated’, but in reality it is additive. Each professional plays their part in a highly co-ordinated, structured and essentially mechanical way, adding layers of expertise into the treatment programme.

With this understanding of how clinical knowledge and practice has built up over the years, it becomes clear why healthcare inflation persists in spite of overall improvements in health in the last fifty years. As the field of knowledge expands and includes more disciplines, more niches within the healthcare system become occupied. These different disciplines need to come together to provide care and treatment for individual patients, so the process becomes more complicated and further resources are needed for co-ordination.

The result of all this activity has been incremental improvement in outcomes of healthcare through the accumulation of marginal gains. In areas of excellence, the precision and co-ordination of activity is impressive. Like mechanics attending a Formula-one racing car in a pit-stop, every member of the team is focused on their part of the task: replacing worn parts, refilling fuel and lubricants, checking all systems are functioning as expected and doing so at break-neck speed to get the car back out on the track.

But the process has limits. Shaving further seconds off the time taken to drive round the circuit requires progressively more effort. This is the law of diminishing returns and is quite evident in healthcare today. In the UK the health budget almost doubled between 2000 and 2010 but the improvement in outcomes was modest. Waiting times were reduced and public satisfaction rose, but to continue to improve at this rate would require an exponential growth in spending with ever decreasing gains for the level of additional investment.

The Birth of the Clinic

Foucault has described how the organisation of healthcare and disease categorisation went hand in hand with the birth of the clinic in the 19th century. This process has shaped the power dynamics and design of healthcare settings ever since.

When hospitals were first created they were very much for the poor. If you were rich the doctor would come to see you at home. Now, the size of specialist teams and equipment, laboratories and the need for sterile environments mean that hospitals have grown in size and complexity and because of economies of scale are often located far from people’s homes. Furthermore, the spatial separation of the patient from his or her home setting removes complex influences on the clinical picture presented to the doctor. It has the effect of negating personal and relational aspects of the causes and effects of the illness, whilst enhancing the disease-focused attention of the clinical gaze. Distancing the patient’s personal circumstances from the frame privileges one form of knowledge over another and shifts the balance of power in healthcare systems from the person seeking help to the supplier.

The extent to which we have lock-in to this model is exemplified by the design of a modern hospital where the spatial segregation is remarkable. There are departments for different parts (ophthalmology) and systems of the body (neurology), different types of diagnostic method (xray, labs) and different types of therapy (OT, physio). The biggest spatial separation lies between illnesses that affect mainly the mind (psychiatry) and those that affect mainly the body. In many cases, people are treated in separate hospitals if they are diagnosed with both a physical and a mental illness.

These observations illustrate the cumulative effect of one perspective — the clinical gaze — on the design of healthcare. Even the word ‘clinical’ has gained a somewhat sinister connotation, meaning an approach that is cold and calculating whilst being highly precise. Similarly the term ‘surgical strike’ denotes a form of precision bombardment. Such language reflects the remoteness of this way of thinking from the layperson and suggests a shadow side to gleaming wards and white coats. The science of anatomy itself is predicated on dissecting a dead body. Learning the physical location of organs and tissues in the body through dissection requires a psychological split for young medical students, much of which is compensated for by black humour.

This separation of the observer from the observed creates a distance between clinical staff and patients. There are understandable psychological reasons for this, mostly associated with anxiety — about death, sickness, pain and loss of control of bodily functions4. However, there are consequences, most notably in the fragmentation of the patient experience. Whilst different clinicians determine the best way to organise healthcare around their own specialisms, each creating a niche for developing expertise, patients feel lost and alienated. Careful attention to ‘customer care’ can alter this experience but fundamentally modern healthcare is provider-driven rather than designed around the needs of the people seeking help.

As noted above, for all the talk of broadening beyond a ‘bio-medical model’ to embrace psychological and social factors, the clinical gaze still tends to locate illness in individuals. This ignores a great deal of the complexity in the way that illness actually manifests in people’s lives. A cranial CT scan, for example, will not help to find the cause of a person’s headache if they are stressed by their partner’s infidelities, financial worries or are being bullied at work. Focusing on lowering individual risk factors such as cholesterol or high blood pressure is unlikely to be effective in preventing heart disease if someone continues to be stressed because of poverty, poor working conditions or family problems. Screening tests, even if they are worthwhile (which is highly marginal in some cases), are unlikely to be taken up by busy working mums with children and ageing parents to worry about.

The Demand for Certainty

It is in the nature of the clinical gaze to seek consistency, reliability, predictability and certainty. In reality, making a diagnosis is much more hazy than either doctors or the public like to think. Despite the emphasis on precision and clarity, results from medical investigations can be interpreted very differently in practice. Studies have shown that when pathologists review each other’s slides they can reach different views on whether a tissue biopsy is cancerous or not5. When a laboratory reports blood chemistry results, these results provide a reference range within which the majority of people lie, yet there may be results outside this range which are not the result of underlying pathology. The results may just be normal for that particular person at the time the sample was taken, or the way the sample was taken and processed may not have been satisfactory. Likewise, imaging techniques may reveal what appears to be a cancerous growth which turns out to be benign. Whatever measuring methods are used, they carry a level of uncertainty.

People want clear answers to the questions...