- 704 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

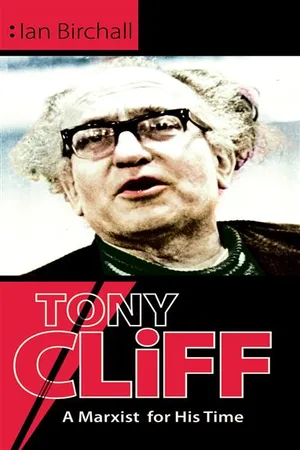

Tony Cliff was a Palestinian Jew who became a revolutionary socialist in his teens. He came to Britain in the 1940s and built the anti-Stalinist left, pulling together the group that was to become the Socialist Workers Party. He died in 2000 aged 82 and thousands attended his funeral procession through Golders Green. This lovingly crafted book is the culmination of years of work, drawing on interviews with over 100 people who knew Cliff and painstaking research in archives around the country. It is a majestic example of political biography at its best.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tony Cliff: A Marxist For His Time by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

THE MAKING OF A REVOLUTIONARY

1

1917-31

The Fateful Question*

May 1917. The First World War raged on. For nearly three years one soldier had died every 15 seconds. But in Britain the longest strike movement of the war, involving 200,000 engineering workers, was taking place. Throughout May the French army was shaken by a wave of mutinies. In Russia there was an uneasy balance – “dual power” – between the Provisional Government which had replaced the Tsar and the grassroots organisation of workers’ soviets. Lenin worked tirelessly to convince the Bolshevik Party of the new possibilities open to it, and prepared to join forces with his old adversary Trotsky. General Sir Edmund Allenby was transferred from France to Egypt, and put in charge of British troops who later that year would capture Jerusalem. Chaim Weizmann and other Zionists vigorously pursued their demand that Palestine should become a Jewish national home; their efforts were rewarded later that year with the Balfour Declaration. An old world was dying; a new one was being born.

The war in Palestine meant constant movement for a Jewish couple of Russian origin, Akiva and Esther Gluckstein. In 1915 they were travelling northwards to Damascus when their third child, Chaim, was born. In 1917 they were moving south again, and came to the village of Zikhron Yaakov, in the vicinity of Haifa. Here lived Dr Hillel Yaffe, a leading Zionist and a medical man committed to the eradication of malaria. He was married to a relative of the Glucksteins, who offered them accommodation in the village.1 There, on 20 May 1917, Esther gave birth to her fourth and last child, Ygael,2 later to be better known as Tony Cliff.

Zikhron Yaakov had been founded in the later 19th century by Baron Edmond de Rothschild, of the French branch of the famous Jewish banking family. Rothschild was a pioneer Zionist, and the colony at Samarin was renamed Zikhron Yaakov in honour of his father, the Baron James de Rothschild (“Zikhron Yaakov” means Memory of James). Such colonies were meant to encourage Jewish settlement in Palestine with an ethos appropriate to the emergent Jewish society. The baron promoted an asceticism which anticipated that of the kibbutzim. At the same time he asserted his own control, wishing his officials to decide which colonists should be allowed to marry. The original purpose of the colony was vine-growing, producing high-quality wine for export. Soon, however, it expanded to include sheep and goat rearing, and arable crops.3 The colony was thus the product of capitalist finance and of Zionism. But it would give birth to one of the most implacable opponents of both Zionism and capitalism.

Zikhron Yaakov was no more than a village, but it grew as a result of economic success. As Simon Schama describes it:

Its population had gone over the 1,000 mark in 1898 but as the number of colonists’ households was only 125, the majority of the residual 500 were employees, tradesmen, and swarms of hangers-on… The result was that what might be called the ancillary services boomed – cafés, taverns, boarding houses – with colonists subletting their own quarters to outsiders.4

A recent Israeli writer, Hillel Halkin, has tried to reconstruct Zikhron Yaakov on the eve of the First World War:

It boasted three streets; nearly one hundred buildings (including a hospital, a bank, and a first sea-view villa, built by a wealthy Jewish couple from England); running water; a stagecoach service to Haifa and Jaffa; one automobile owner; two licensed bottlers of seltzer water; and one thousand inhabitants divided into six categories – colonists, ICA [Israelite Colonisation Association] officials, independent professionals and artisans, Second Aliyah laborers, Yemenites, and Arab help quartered in the farmyards. It was the second-largest Jewish village in Palestine and it took pride in being called by its sister colonies, with a mixture of mockery and envy, the “little Paris” of the East.5

The Glucksteins were a relatively prosperous family who had arrived in Palestine from Russia in 1902. Akiva Gluckstein was born in 1881 and his wife, Esther Voyseisky, in 1886.6 They had come at the very beginning of the wave of Russian settlers who arrived early in the 20th century. These immigrants, sometimes called “Muscovites”, were in many ways different from the earlier generation of colonists encouraged by Rothschild. They often professed radical, even revolutionary ideas, yet were more committed to the creation of an all-Jewish economy. Whereas the earlier settlers had found Arab workers cheaper and more productive, the new settlers insisted that employing Jewish labour was a matter of principle.7

Akiva’s elder brother was a banker of decidedly right-wing views. He himself was in the construction industry. His business partner at one time was Yehiel Mikhail Weizmann (known as “Chilik”), the youngest brother of the first president of Israel, Chaim Weizmann (not, as Cliff wrongly claims in his autobiography, Chaim Weizmann himself8). It is hard to establish when this partnership was formed, or how long it lasted. Weizmann settled in Palestine in 1914, after studying agriculture in Berlin. From 1920 to 1928 he was assistant director of the Palestine Government Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. So his partnership with Gluckstein must have belonged to the period of the world war or its immediate aftermath.9 In particular Gluckstein was involved in the construction of sections of the Hedjaz Railway, built to take Muslim pilgrims from Turkey to Mecca and Medina. The railways played a major strategic role in the First World War, and were an important contribution to the modernisation of Palestine.10 *

Gluckstein was a handsome, jovial man, greatly liked by those who knew him.11 He was a born actor; he loved to tell jokes, and though he constantly told the same stories, he always varied them. In later life he joined a Yiddish theatre company and travelled around the country with it. He retained his curiosity and zest for life into old age. In the 1960s he travelled to Europe to see his son and grandchildren. He spoke no English, but had recently learnt French to prepare for the journey.12 Certainly he belonged to a cosmopolitan tradition; many years later Cliff recalled, “My father used to say to me, ‘I can sign my name in nine languages.’ That was true. ‘But the cheques always bounce’.”13

Esther, his wife, was a bookish woman; she read Russian, Hebrew, French and German. Even in hospital during her final illness she was always reading.14 She also had a lively sense of humour. Physically Ygael resembled his mother, a small woman. He was a sickly child, and for a long time had to be carried around in his mother’s arms. He didn’t start to talk until he was about four years old15 – something he amply made up for in later years.* He acquired his mother’s intellectual interests, while his father’s humour and theatricality later appeared in his speaking style.

The new child had two brothers and a sister. His elder brother, Shimon, became a veterinary surgeon; the younger, Chaim, had more literary interests and was for a time a revolutionary. The sister, Alexandra (Alenka), was a talented musician; she went to Vienna to study music, but found the standards too exacting; in the 1940s she suffered acute depression and committed suicide.16 Though in later life Ygael was surrounded by people with artistic gifts (including his wife and younger son), his own artistic side stayed underdeveloped.

As a well-respected prosperous commercial family, the Glucksteins were at the heart of the Jewish community. As well as the Weizmanns, David Ben-Gurion (later the first prime minister of Israel) was a family friend. The Jewish community was still small – at the time of Ygael’s birth there were some 60,000 Jews in Palestine, and more than half a million Arabs. Many of the Jews were immigrants who had arrived since 1900. Ygael was one of the new generation of Palestine-born Jews – sabras as they were called after one of the native plants of Palestine, the edible cactus known as the “prickly pear”.

How did the prickly pear embark on the hard road that would take him to revolutionary socialism? Why did one born at the heart of the Zionist project break with it so dramatically? One explanation that can be rejected is that his revolutionary ideas originated in family tensions. It has often been argued that revolutionary hostility to capitalism results from a displacement of anger directed at the parents.* In Ygael’s case, such analyses do not fit the facts. He was a well-loved, even spoilt child who stayed on good terms with his parents. They were not enthusiastic about his conversion to revolutionary socialism – he later recorded that when he was first arrested his father consoled his mother by predicting that he would soon grow out of it!17 But it never caused conflict or division in the family. When his father visited England many years later, it must have been a shock to find his son so deeply involved in revolutionary politics, but he showed no antagonism, simply evading any political discussion.18

Ygael’s happy childhood was reflected in his later family life. Cliff was one of the most single-minded people it is possible to imagine – but if there was one thing to which he was devoted other than revolutionary socialism, it was his wife and four children. If Ygael grew to hate the capitalist system, that hatred was not a deflected hostility to his family. He hated the system because, as his life’s work showed, there was good reason to hate it.

While the young Ygael struggled to walk and speak, monumental changes were taking place. In the Glucksteins’ homeland Lenin and the Bolsheviks were establishing a new society based on working class rule. The Ottoman Empire had collapsed and Palestine had fallen into the hands of the British, who continued to occupy it under the terms of a League of Nations Mandate (1922). Seven thousand British troops plus civil servants, teachers and police were brought into the country to establish a colonial regime.

From the outset this was based on deception and duplicity. Contradictory promises were made to Jews and Arabs. There were many divisions in the British ruling class and in the British administration in Palestine. Among those responsible for British policy there were both pro-Zionists and anti-Semites (some, like Winston Churchill, were both).19 But while British policy went through many turns and inconsistencies, it was clear that British imperialism would opt for Zionism.

Ygael was too young to be aware of any of this. But the adults who surrounded him must have followed the course of events with keen interest. Doubtless the words “revolution”, “communism” and “empire”, perhaps even the names of Lenin and Trotsky, reached his infant ears. Probably too he heard the name “London”, a faraway city where decisions about the future of Palestine were being taken. No one in the family can have imagined that he would spend the last 50 years of his life in one of the poorer areas of the imperial capital.

Ygael’s first educational experience was in a Montessori kindergarten. The Montessori method was at the height of its worldwide popularity, and was used in a number of Jewish kindergartens in the 1920s.20 It was based on the premise that children are capable of self-d...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgements

- Libraries

- Abbreviations

- Key dates

- A note on sources

- About the Author

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One: The Making of a Revolutionary

- Part Two: From Theory to Practice

- Part Three: Building for the Future

- Bibliography of Cliff’s works

- Notes

- Index