- 295 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

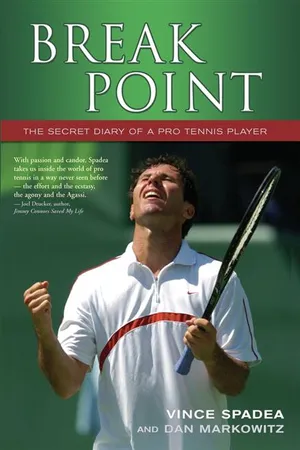

Groomed since the age of eight by his obsessive father, Spadea, by most accounts, has been a success. At the start of the 2005 season, 19th seed Spadea was the only 30+ year old player besides Agassi to be ranked in the top 20 on the world pro circuit. Spadea gives a riveting account of the ultra-competitive and often hilarious world of a pro tennis player. He battles injuries, coaching and agent changes. Agassi, Roddick, Federer, Nadal, Navratilova, Sharapova, Henman and Safin are analysedin more colourful and personal terms than the tennis media has ever provided...

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Break Point by in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Ecw Press DigitalYear

2010Print ISBN

9781550227291eBook ISBN

9781554902705PART I

ON THE ROAD

JANUARY 4, 2005

Auckland, New Zealand

A Qantas 747 airliner sets tire marks on the Auckland airport runway. Sweat is dripping from my forehead. I have both a backache and headache. For the past 14 hours after leaving Los Angeles International Airport — 14 hours in a machine 30,000 feet above a deep blue sea — I’ve been crammed into a coach seat. Now I’ve finally arrived in New Zealand, my eleventh trip to this part of the Pacific.

This is crazy. I’m restless, anxious, barely self-contained as I realize how far I have just traveled to play in a tennis competition. When you’re on the tour for 12 years, more than occasionally you have what can only be characterized as Trips from Hell. I had occupied the last seat on the plane, 72H, and it didn’t even fully recline. I felt like a packed sardine, knees to my chest, no elbow room, limited food and drink offerings. When we finally landed, I was dehydrated and delirious. This is just two days after I’d celebrated New Year’s in L.A. with friends and family, making this trip more sentimental and emotional than most.

Spadea arriving in New Zealand, on New Year’s I was dancing on the ceiling, now I’m squealing, appealing, praying and kneeling, but 2005 has begun, Vince gotta continue the run, gonna have more fun than when I turned 21.

This is the unglamorous side of a tennis professional’s life. The travel is one of the main reasons you see so few players over 30 years old on the tour these days. When players start thinking of retirement, especially champions like Sampras and Pat Rafter, who have earned more money and glory than they could expect in ten lifetimes, it’s the excessive travel that curtails their careers more than anything else. The time spent in airports, on planes, in taxis — and the delays of missing luggage and drivers who get lost on the way to the tournament hotel or courts — wears on one’s stamina and patience. Björn Borg retired for the first time at 25; Sampras retired for good at the “old” age of 31, and Rafter, at 29.

This life of being constantly on the road, away from family and friends for ten months of the year — that’s right, ten months is the length of one pro tennis season — gets to you every now and then. It’s getting to me right now, and I’m preparing to play just my first tournament of the season. I’d played my last tournament of 2004 at the end of October, and then I was on the American Davis Cup team that played the finals into December in Spain. So I’d had less than one month of an off-season — if you can call practicing twice a day for two of those weeks and working out every day in the gym downtime.

Okay, so you’re thinking, “What a spoiled brat this guy is. He gets to fly to New Zealand and Australia to play tennis, and he’s complaining about it.” But what some of you might not realize is that there’s a major difference between taking a relaxing vacation and traveling to “go to work.” This journey is costing me around $7,000 in airplane tickets, hotel rooms, and coaching fees for three weeks in which I will play two tournaments, one here in New Zealand, and then the big one in Australia, the first Grand Slam of 2005, the Australian Open. Usually, I also play the tournament in Adelaide before Auckland, but this year, because of my short off-season, I decided to skip that one.

I’ve made this exact trip 11 times now — no questions asked — having missed it only in 1993 when I was just starting out on tour, and in 1997 because I had a back injury. In 2002, I made the trip Down Under, but my slump had dropped my ranking so low I had to try to qualify for the Australian Open. After I lost in the qualies, I flew to play a lower-level pro tournament called a Challenger in Hawaii, where I beat Michael Chang in the quarters. It was my first win over the former No. 2 player in the world in five matches, and I never played him again because he retired in 2003.

Once I get here, there’s not a lot of time to sightsee. It’s just basically back-and-forth shuttles between the hotel and tennis courts. It’ll be that way in every city I play in now for the next 40-plus weeks, in cities ranging from Indianapolis to Tokyo. Believe me, this isn’t exactly the trip to New Zealand you’d want to win on The Price Is Right. At this point, I certainly would have chosen the other showcase, the one with the new car. But I just read a mission trip to Mars on a space shuttle would take at least six months, so enough with the crying.

The good news is that I’m here and I want to be here. It’s a new year to pursue my 2005 goals of making a surge into the Top 15 players ranked in the world. I’m setting new sights, trying to move into uncharted territory for myself. The Top 20 is the best I’ve ever achieved — I’m No. 19 right now — but I’m looking forward to moving up and making an impact in the Grand Slams, possibly making the semis or the finals of one or two, and make people wonder, “Can you believe this kid from the dirty south of Florida? Who’s had such a roller-coaster ride both physically and mentally? He went into this tennis season and would not go away. Spadea is not dying, he’s not fading; he’s getting stronger as he gets older. How does this guy do it?”

I’m starting out in the Kiwi nation, the city of Auckland to be exact, a wonderful, cosmopolitan capital city. I’m greeted A-list style, by a chauffeur carrying a sign that reads, “Spada.” Okay, missed it by one vowel, but at least I got the driver, right? My new coach — there will be plenty of time to talk about coaches later, because I’ve had about 30 since my father, Vincent Sr., stopped being my coach about five years ago — is Greg Hill, one of Nick Bollettieri’s main men. Greg played on the pro tour for a four-year stretch in the mid-1980s, and his claim to fame is that he beat Agassi when Andre was, like, 16 and first coming up.

Greg and I get situated in the picturesque tournament hotel, just minutes away from the beautiful Viaduct Harbour, which was home to the 2003 America’s Cup. From my room, there are fantastic views of the water, yachts, and islands nearby. Dozens of hip bars and restaurants line the water-front, and crowds pace through the area even as the notorious winds and occasional showers blow and drip.

But I’m not here to get too comfortable. I take a short two-hour snooze and then we set out for the courts. How do you make it to the semifinals of the Australian Open? Practice my friend, practice! Except my right shoulder is sore — I played 80 matches the previous season, including doubles, and I might have overdone it, so I can’t hit for too long.

JANUARY 11

The Auckland Open is a cozy, well-run, fun tournament to start the year off. I’m still having mixed feelings being here because of the short off-season. In one respect, I’m confident and eager to continue my run up the rankings — in 2004 I rose from No. 29 to No. 19 in the world — and I want to pursue new and heightened goals. I’d worked hard on and off the court in November and December, improving tennis techniques, quickness, fitness, nutrition, and mental conditioning. But on the other hand, the last tournament of 2004 ended on November 7th, and here I was back in full blast mode on the 6th of January. I would have liked to have another month off.

Three years ago, I started training some in Los Angeles during the off-season instead of in my native Florida, where I own a home in Boca Raton. After my ranking plummeted in 2000, I started working with Dr. Pete Fischer, the architect of Pete Sampras’ game, and he has played an important role in my comeback. I started to believe in my skills again when I went to Fischer. I needed something new — some new blood — and a fresh and interesting way of playing.

I’ve always been a backcourt grinder, relying on my ground strokes and legs to beat opponents. Fischer is famous for developing Sampras’ nonpareil serve, and his great frontcourt volley game. He taught me Sampras’ service motion, and coached me to take more chances and end points quicker. He provided me with more artillery and better mechanics. Fischer focuses on hitting the ball wide to a certain depth area. He says it’s stupid to miss long, because even if the shot lands in, your opponent will probably be able to return it. You hit winners by taking people off the sides of the court, rather than hitting balls deep toward the baseline.

Because Fischer had been a pediatrician and was convicted of child molestation in 1997 — serving three years in a federal penitentiary — we had to practice at the courts in his housing complex in Rolling Hills, because he was still under probation. I had to drive about an hour and a half from my sister Diana’s apartment in Hollywood — where I was staying — to practice under Fischer’s tutelage.

Everyone’s a strange cat in tennis. When I sought out Fischer, I felt I was getting the best person in the game to help me. Like an actor struggling with his craft, I called the Stella Adler of tennis. (Adler was Marlon Brando’s acting coach.) I knew about Fischer’s past, but I was in no position to be choosy. Not only had Fischer developed Sampras’ game, he had helped him develop his attitude — and I needed an attitude change.

As I traveled to Challenger tournaments in 2001, playing in places like Tulsa, Oklahoma, Tyler, Texas, and Granby, Quebec, I would call Fischer before each match and he would give me my game plan. In two years’ time, I’d regained my Top 100 ranking and began playing the main tour events in places like Wimbledon, Miami, and Monte Carlo.

But recently I’ve noticed a change in Fischer. He doesn’t seem to care as much about how I do. I’m not sure if it comes from the way I’ve operated with him or just the way he’s started dealing with the situation. I almost feel like he’s decided, “Y’know, I’ve been with this guy for a few years, and he’s only going to be so good. And that’s not good enough for me.”

About eight months ago, I started working out at the IMGAcademy run by Nick Bollettieri in Bradenton, Florida. Nick revolutionized the game back in the 1980s by developing ground-stroke kings in Jimmy Arias, Aaron Krickstein, Agassi, and Jim Courier. He’s in his seventies now, but he’s still passionate about tennis.

Bollettieri’s is like a military school for tennis. “We start at nine o’clock in the morning,” Bollettieri says. I like to start about 10 or 10:30 for my first practice of the day. But Nick wouldn’t hear of it. “Show up at nine o’clock in the morning,” he told me. “You hear me? You hear me. Okay, son, okay boy.” He’s a disciplinarian. He easily flies off the handle. “Oh, what the heck, son. You can’t go around with that kind of back swing. You want it right here. No higher, alright, you hear me? Alright, boy.”

Nick believes I should play more like Andre, by owning the baseline and striking first, dominating with big forehands and backhands. He put me up against two of his teenage players at the Academy and stood behind me yelling, “Get your racket back, get it back faster. You take it back from 12 o’clock to 9 o’clock. That’s too long, son. You’re wasting too much time. C’mon, move, move.” Nick’s instruction is always short and sweet. It’s 15 intense minutes, and then he walks over to another court and comes back 40 minutes later to make sure that you’re doing what he told you earlier.

So I am now at a crossroads in my game, somewhere between how Fischer wants me to play and the way Greg Hill, my traveling coach and a Bollettieri disciple, is telling me how to play. When I talked to Fischer about it, he said, “We know Agassi’s style can be successful when it’s being done by Agassi. But I don’t see anyone who has been able to imitate him and have success. You mention David Nalbandian, but Nalbandian can’t hit a backhand like Agassi. The difference between Nalbandian and Agassi is that if Nalbandian wins eight more majors, he’ll be tied with Agassi.

“Agassi does what he does because he’s inside the court. You might be able to pick up the ball as fast as Agassi on your backhand, but nobody’s going to hit the ball to your backhand. It doesn’t make a lot of sense to me for you to look to put away a forehand shot if the ball is one inch inside the baseline. I’d much rather see you wait until you have a high forehand and then go in and clock it. You’ve got to look for the chance to move forward, Vince. You can’t say, ‘I can stay inside the court like Andre,’ because you can’t. The only other person who did it was (Jimmy) Connors.

“I’ve already told you what I think. You’ve gone as far as you’re going to get being a pure defensive player, and you’re never going to be a great offensive player, because at 30, you’re not going to develop a weapon. You’ve got to maintain your defensive skills, and get enough offense so you can win a few more points that will translate to winning a few more matches. You’re never going to be Top 10 in the world. Staying inside the Top 20, like you are now, should be your goal for the next couple of years.”

I never like to be told that I’ve reached my peak. Agassi won five Grand Slam tournaments (three Australian Open, one Roland Garros, and one U.S. Open) from the ages of 29 to 33. Rod Laver swept all four Grand Slam tournaments in one year — a Grand Slam (something only Don Budge and he accomplished in the men’s game) — at 31. Rocky Marciano won the heavyweight crown at 30, and held it for four years until he retired. I respect Fischer’s opinion, but I don’t want to work with a coach who doesn’t believe in my abilities or my potential to get better.

With Fischer’s and Bollettieri’s competing strategies playing out in my mind, I step out onto the hard courts in Auckland for my first match of the 2005 season against David Sanchez of Spain. Sanchez is mainly a clay-court player, but he’s feisty and fit, and there is never a sure thing in men’s pro tennis. I’m the No. 4 seed in the tournament — only Guillermo Coria of Argentina, Tommy Robredo of Spain, and Dominik Hrbaty of Slovakia are seeded ahead of me — so my match is the feature of the night session.

From the second the umpire asks, “You guys ready to go? Good luck,” I’m all business. But before a tennis match actually begins, it’s scary. When I first came up on the pro tour, before my matches, I used to think, “I’m in a scary world right now, and I hope to God I win.” You don’t know what’s going to happen. All the questions are unanswerable at that moment. “What if I don’t win? Where am I going to go after this? Why am I doing this? What am I trying to accomplish?”

It’s the element of the unknown that gets to you, the fear of being out there naked, not knowing how the match is going to go, what points are going to be crucial to win, and more importantly, whether you can hit the shots on those big points? Have you prepared and worked hard enough, punished yourself enough? How fit are you? How well are you going to focus?

It’s a very scary thing. And it’s no less scary today than it was when I was 17. I think I’ll know I’ve lost my passion and fire to play the game when I no longer feel scared before a match. Now I like that empty feeling of fear in my stomach, because I know that I want to win — I need to win — and I’m going to do anything to win, at any cost. When I have the opposite feeling before a match — “I’ve been here, done that” — I know I’m going to get sloppy and lose my concentration out there. I might let up and not get off to a good start. I might get annoyed and have a bad attitude, and then I won’t have a good result. No, it’s good to feel scared.

The match starts at 7 p.m., and by the time it’s 7:48 p.m., I’m shaking hands with my Spanish opposition, telling him “tough luck.” Tough luck, I’m thinking, but not for me. I had just recorded a win in 48 minutes by the score of 6–0, 6–0. No typos in that score; I’d won every single game of the match! I’d never double-bageled an opponent in my 12 years on tour. Winning in this fashion in the first match of the year is extremely rare and pretty eye-opening. The ATP officials at the tournament said it had been more than a year — Doha, Qatar, in the first week of January 2004 — since a 6–0, 6–0 match had been played on the pro tour. I played well, and Sanchez had had an off day. I won all the big, close points and that helped to make the final score so lopsided.

I’m going to sleep well in Auckland tonight.

JANUARY 12

It’s nice for my confidence to know that I can vanquish another pro player so soundly, still I don’t start out with a one-set lead in today’s second-round match just because I won the first one 6–0, 6–0. I wanted to appreciate my feat, but not dwell on it too much. I needed to prepare and focus for my next opponent, Robby Ginepri from the U.S. Robby is a friendly, easygoing dude, a 22 year old born in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He’d made it to the round of 16 at both the Australian Open and Wimbledon last year, and reached a career-high ranking of No. 23, but had slipped recently to No. 63. I’ve played him only once, last year on a fast, indoor hard court, and beat him in straight sets.

Ginepri’s age cannot be used as an explanation for his slide in the rankings. When I started my precipitous drop, I had just completed the summer of 1999, in which I made it to the finals at Indianapolis and the round of 16 at the U.S. Open. I had attained my highest ranking, No. 18, and at 25, I seemed on my way to bigger and better results. But then I lost in the first round in six of the last seven tournaments I played in ‘99, and that snowballed into not winning another match until Wimbledon 2000.

Some so-called experts came out then and said they suspected I had reached my plateau in my early twenties. There must be something innate in humans that we love to see precious, precocious teenage wonders conquer the adult world with early success. It’s a novelty to achieve the seemingly “impossible” at such a young age. Maybe this fascination with young achievers comes from a lifelong personal dream of ours lived vicariously through the young, rich, and beautiful star.

The majority of us don’t want to get old. Old is bad, young is good, and this sentiment is only heightened in a sport like tennis, where a Boris Becker wins Wimbledon at 17, and great champions like Björn Borg and John McEnroe never won a Grand Slam title after the age of 25. It’s not a healthy outlook, but it’s alive and well and passed down from generation to generation.

At 30, people in the tennis world I live in consider me to be like a broken-down racehorse, old and unexciting. I don’t overpower my opponents with 140-mile-per-hour serves, or flex my biceps, pump my fists, or lambaste umpires over bad calls. I have the feeling that even if I were to perform spectacularly — say, win the Australian Open — the simple truth is I live in a world that cherishes the protegé, the wunderkind, the 15-year-old genius (Donald Young, who turns pro before graduating from high school, or the 17-year-old gorgeous, tall, blond, Maria Sharapova, who beat Serena Williams to win Wimbledon) would make it seem like an aberration rather than a feat of great perseverance.

I know that regardless of age, I haven’t won enough throughout my career to become a household name. My name is not foremost in the minds of the world’s — or even American — tennis fans. A lot of people still think I’m from Spain because of my name and how I look (my father is Italian-American and my mother is originally from Colombia). I know that if I won more, people would learn how to pronounce my name (Spadea rhymes with afraid-a-ya) and spell it correctly, no matter how difficult it might be.

Leaving such thoughts behind — they don’t help me on the court — it’s Spadea vs. Ginepri time, the unheralded vs. t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Prologue The Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde of Andre Agassi

- Winter 2004 Davis Cup Finals (or Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff) Seville, Spain

- Part I on the Road

- Part II Coming Home

- Part III Wild Women and Song

- Part IV The Crown Jewels: Wimbledon and The U.S. Open

- Appendix A 2005 Tournament Season

- Appendix B Vince Spadea’s ATP Player Profile (as of March 2006)