- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

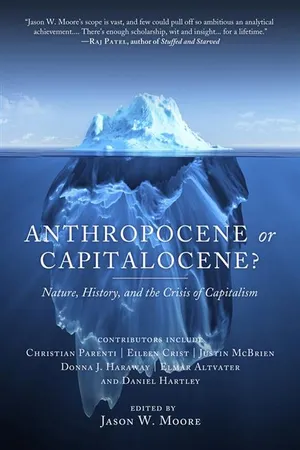

About this book

The Earth has reached a tipping point and we are entering an era of unprecedented turbulence in humanity's relationship within the web of life. But just what is that relationship, and how do we make sense of this extraordinary transition? Anthropocene or Capitalocene? offers answers to these questions. The contributors to this book diagnose the problems of Anthropocene thinking and propose an alternative: the global crises of the 21st century are rooted in the Capitalocene; not the Age of Man but the Age of Capital.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

The Anthropocene and Its Discontents

Toward Chthulucene?

ONE

On the Poverty of Our Nomenclature

“Nature is gone…. You are living on a used planet. If this bothers you, get over it. We now live in the Anthropocene—a geological epoch in which Earth’s atmosphere, lithosphere and biosphere are shaped primarily by human forces.”

“When all is said and done, it is with an entire anthropology that we are at war. With the very idea of man.”

The Anthropocene is a discursive development suddenly upon us, a proposed name for our geological epoch introduced at century’s turn and now boasting hundreds of titles, a few new journals, and over a quarter million hits on Google. This paper’s thesis is an invitation to consider the shadowy repercussions of naming an epoch after ourselves: to consider that this name is neither a useful conceptual move nor an empirical nobrainer, but instead a reflection and reinforcement of the anthropocentric actionable worldview that generated “the Anthropocene”—with all its looming emergencies—in the first place. To make this argument I critically dissect the discourse of the Anthropocene.

In approaching the Anthropocene as a discourse I do not impute a singular, ideological meaning to every scientist, environmental author, or reporter who uses the term. Indeed, this neologism is being widely and often casually deployed, partly because it is catchy and more seriously because it has instant appeal for those aware of the scope of humanity’s impact on the biosphere. Simply using the term Anthropocene, however, does not substantively contribute to what I am calling its discourse—though compounding uses of the term are indirectly strengthening that discourse by boosting its legitimacy.

By discourse of the Anthropocene I refer to the advocacy and elaboration of rationales favoring the term in scientific, environmental, popular writings, and other media. The advocacy and rationales communicate a cohesive though not entirely homogeneous set of ideas, which merits the label “discourse.” Analogously to a many-stranded rope that is solidly braided but not homogeneous, the Anthropocene discourse is constituted by a blend of interweaving and recurrent themes, variously developed or emphasized by its different exponents. Importantly, the discourse goes well beyond the Anthropocene’s (probably uncontroversial) keystone rationale that humanity’s stratigraphic imprint would be discernible to future geologists.

The Anthropocene themes braid; the braided “rope” is its discourse. Chief among its themes are the following: human population will continue to grow until it levels off at nine or ten billion; economic growth and consumer culture will remain the leading social models (many Anthropocene promoters see this as desirable, while a few are ambivalent); we now live on a domesticated planet, with wilderness2 gone for good; we might put ecological doom-and-gloom to rest and embrace a more positive attitude about our prospects on a humanized planet; technology, including risky, centralized, and industrial-scale systems, should be embraced as our destiny and even our salvation; major technological fixes will likely be needed, including engineering climate and life; the human impact is “natural” (and not the expression, as I argue elsewhere, of a human species-supremacist planetary politics [see Crist 2014]); humans are godlike in power or at least a special kind of “intelligent life,” as far as we know, “alone in the universe”; and the path forward lies in humanity embracing a managerial mindset and active stewardship of earth’s natural systems.

Of equal if not greater significance is what this discourse excludes from our range of vision: the possibility of challenging human rule. History’s course has carved an ever-widening swath of domination over nature, with both purposeful and inadvertent effects on the biosphere. For the Anthropocene discourse our purposeful effects must be rationalized and sustainably managed, our inadvertent, negative effects need to be technically mitigated—but the historical legacy of human dominion is not up for scrutiny, let alone abolition (Crutzen and Stoermer 2000, 18).

The commitment to history’s colonizing march appears in the guise of deferring to its major trends. The reification of the trends into the independent variables of the situation—into the variables that are pragmatically not open to change or reversal—is conveyed as an acquiescence to their unstoppable momentum. Paul Ehrlich and John Holdren’s famous formula (1971) that human Impact (“I”) equals Population times Affluence times Technological development (“PAT”) encapsulates some of the paramount social trends which appear to have so much momentum as to be virtually impervious to change. The recalcitrant trends are also allowed to slip through the net of critique, accepted as givens, and consequently projected as constitutive of future reality.

In brief, here is what we know: population, affluence, and technology are going to keep expanding—the first until it stabilizes of its own accord, the second until “all ships are raised,” and the third forevermore—because history’s trajectory is at the helm. And while history might just see the human enterprise prevail after overcoming or containing its self-imperiling effects, the course toward world domination should not (or cannot) be stopped: history will keep moving in that direction, with the human enterprise eventually journeying into outer space, mining other planets and the moon, preempting ice ages and hothouses, deflecting asteroid collisions, and achieving other impossible-to-foresee technological feats:

Looking deeply into the evolution of the Anthropocene, future generations of H. sapiens will likely do all they can to prevent a new ice age by adding powerful artificial greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Similarly any drops in CO2 levels to low concentrations, causing strong reductions in photosynthesis and agricultural productivity, might be combated by artificial releases of CO2, maybe from earlier CO2 sequestration. And likewise, far into the future, H. sapiens will deflect meteorites and asteroids before they could hit the Earth. (Steffen et al. 2007a, 620)

The Anthropocene discourse delivers a Promethean self-portrait: an ingenious if unruly species, distinguishing itself from the background of merely-living life, rising so as to earn itself a separate name (anthropos meaning “man,” and always implying “not-animal”), and whose unstoppable and in many ways glorious history (created in good measure through PAT) has yielded an “I” on a par with Nature’s own tremendous forces. That history—a mere few thousand years—has now streamed itself into geological time, projecting itself (or at least “the golden spike” of its various stratigraphic markers3) thousands or even millions of years out. So unprecedented a phenomenon, it is argued, calls for christening a new geological epoch—for which the banality of “the age of Man” is proposed as self-evidently apt.

Descriptions of humanity as “rivaling the great forces of Nature,” “elemental,” “a geological and morphological force,” “a force of nature reshaping the planet on a geological scale,” and the like, are standard in the Anthropocene literature and its popular spinoffs. The veracity of this framing of humanity’s impact renders it incontestable, thereby also enabling its awed subtext regarding human specialness to slip in and, all too predictably, carry the day.

In the Anthropocene discourse, we witness history’s projected drive to keep moving forward as history’s conquest not only of geographical space but now of geological time as well. This conquest is portrayed in encompassing terms, often failing to mention or nod toward fundamental biological and geological processes that humans have neither domesticated nor control (Kidner 2014, 13).4 A presentiment of triumph tends to permeate the literature, despite the fact that Anthropocene exponents have understandable misgivings—about too disruptive a climate, too much manmade nitrogen, or too little biodiversity. “We are so adept at using energy and manipulating the environment,” according to geologist Jan Zalasiewicz, “that we are now a defining force in the geological process on the surface of the Earth” (quoted in Owen 2010).5 “The Anthropocene,” the same author and colleagues highlight elsewhere, “is a remarkable episode in the history of our planet” (Zalasiewicz et al. 2010). Cold and broken though it be, it’s still a Hallelujah. The defining force of this remarkable episode—the human enterprise—must contain certain aspects of its “I,” but, in the face of all paradox, PAT will continue to grow, and the momentum of its product will sustain history’s forward thrust. Extrapolating from the past, but not without sounding an occasional note of uncertainty, Anthropocene supporters expect (or hope) that this forward movement will keep materializing variants of progress such as green energy, economic development for all, a gardened planet, or the blossoming of a global noosphere.

How true the cliché that history is written by the victors, and how much truer for the history of the planet’s conquest against which no nonhuman can direct a flood of grievances that might strike a humbling note into the human soul. Adverse impacts must be contained insofar as they threaten material damage to, or the survival of, the human enterprise, but the “I” is also becoming linguistically contained so that its nonstop chiseling and oft-brutal onslaughts on nature become configured in more palatable (or upbeat6) representations. The Anthropocene discourse veers away from environmentalism’s dark idiom of destruction, depredation, rape, loss, devastation, deterioration, and so forth of the natural world into the tame vocabulary that humans are changing, shaping, transforming, or altering the biosphere, and, in the process, creating novel ecosystems and anthropogenic biomes. Such locutions tend to be the dominant conceptual vehicles for depicting our impact (Kareiva et al. 2011).7

This sort of wording presents itself as a more neutral vocabulary than one which speaks forcefully or wrathfully on behalf of the nonhuman realm. We are not destroying the biosphere—we are changing it: the former so emotional and “biased”; the latter so much more dispassionate and civilized. Beyond such appearances, however, the vocabulary of neutrality is a surreptitious purveyor (inadvertent or not) of the human supremacy complex,8 echoing as it does the widespread belief that there exist no perspectives (other than human opinion) from which anthropogenic changes to the biosphere might actually be experienced as devastation. The vocabulary that we are “changing the world”—so matter-of-factly portraying itself as impartial and thereby erasing its own normative tracks even as it speaks—secures its ontological ground by silencing the displaced, killed, and enslaved whose homelands have been assimilated and whose lives have, indeed, been changed forever; erased, even.

And here also lies the Anthropocene’s existential and political alliance with history and its will to secure human dominion: history has itself unfolded by silencing nonhuman others, who do not (as has been repeatedly established in the Western canon9) speak, possess meanings, experience perspectives, or have a vested interest in their own destinies. These others have been de facto silenced because if they once spoke to us in other registers—primitive, symbolic, sacred, totemic, sensual, or poetic—they have receded so much they no longer convey such numinous turns of speech, and are certainly unable by now to rival the digital sirens of Main Street. The centuries-old global downshifting of the ecological baseline of the historically sponsored, cumulative loss of Life10 is a graveyard of more than extinct life forms and the effervescence of the wild. But such gossamer intimations lie almost utterly forgotten, with even the memory of their memory swiftly disappearing. So also the Earth’s forgetting projects itself into humanity’s future, where the forgetting itself will be forgotten for as long as the Earth can be disciplined into remaining a workable and safe human stage. Or so apparently it is hoped, regarding both the forgetting and the disciplining.

Not only is history told from the perspective of the victors, it often also conceals chapters that would mar its narration as a forward march. Similarly, for humanity’s future, the Anthropocene’s projection of a sustainable human empire steers clear of envisioning the bleak consequences of the further materialization of its present trends. What is offered instead are the technological and managerial tasks ahead, realizable (it is hoped) by virtue of Homo sapiens’s distinguished brain-to-body ratio and related prowess. In a 2011 special issue on the Anthropocene, the Economist (a magazine sweet on the Anthropocene long before the term was introduced) highlights that what we need in the Age of Man is a “smart planet” (2011a, 2011b). As human numbers and wealth continue to swell, people should create “zero-carbon energy systems,” engineer crops, trees, fish, and other life forms, make large-scale desalinization feasible, recycle scrupulously especially metals “vital to industrial life,” tweak the Earth’s thermostat to safe settings, regionally manipulate microclimates, and so forth, all toward realizing the breathtaking vision of a world of “10 billion reasonably rich people.”

When history’s imperative to endure speaks, the “imagination atrophies” (Horkheimer and Adorno 1972, 35). There is the small thing of refraining from imagining a world of 10 billion reasonably rich people (assuming for argument’s sake that such is possible)—a refraining complied with in the Anthropocene discourse more broadly. How many (more) roads and vehicles, how much electrification, how many chemicals and plastics at large, how much construction and manufacturing, how much garbage dumped, incinerated, or squeezed into how many landfills, how many airplanes and ships, how much global trade11 and travel, how much mining, logging, damming, fishing, and aquaculture, how much plowing under of the tropics (with the temperate zone already dominated by agriculture), how many Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (aka factory farms)—in brief, how much of little else but a planet and Earthlings bent into submission to serve the human enterprise?

Ongoing economic development and overproduction, the spread of industrial infrastructures, the contagion of industrial food production and consumption, and the dissemination of consumer material and ideational culture are proliferating “neo-Europes”12 everywhere (Manning 2005). The existential endpoint of this biological and cultural homogenization is captured by the Invisible Committee’s description of the European landscape:

We’ve heard enough about the “city” and the “country,” and particularly about the supposed ancient opposition between the two. From up close, or from afar, what surrounds us looks nothing like that: it is one single urban cloth, without form or order, a bleak zone, endless and undefined, a global continuum of museum-like hyper-centers and natural parks, of enormous suburban housing developments and massive agricultural projects, industrial zones and subdivisions, country inn...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism - Jason W. Moore

- Part I: The Anthropocene and Its Discontents: Toward Chthulucene?

- Part II: Histories of the Capitalocene

- Part III: Cultures, States, and Environment-Making

- References

- Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Anthropocene Or Capitalocene? by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.