- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

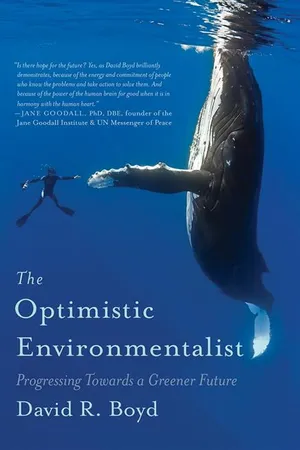

Yes, the world faces substantial environmental challenges - climate change, pollution and extinction. But the surprisingly good news is that we have solutions to these problems. In the past 50 years, a remarkable number of environmental problems have been solved, while substantial progress is ongoing on others. The Optimistic Environmentalist chronicles these remarkable success stories, from saving endangered species to creating national parks that conserve land and resources. A bright green future is not only possible, it's within our grasp.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part 1

The Big Picture

Chapter 1

Nature’s Comeback Stories

THE MEDIA REGULARLY REPORTS heart-rending stories about species pushed to the brink of extinction by human malfeasance—overhunting, overfishing, destroying habitat, introducing alien species, and spewing toxic substances into the environment. It’s true that the rate of extinctions has accelerated in recent centuries. Despite this, many species are enjoying remarkable comebacks because we’ve smartened up and improved our once-damaging ways.

One of the first memorable slogans of the environmental movement in the early 1970s was “Save the Whales.” Who can forget the iconic image of the first Greenpeace activists in a tiny Zodiac, buzzing around a Russian whaling vessel like an agitated bumblebee trying to protect its honey from a bear? You don’t hear about saving the whales that often anymore, because many whale species are making extraordinary comebacks.

From my little writing cabin overlooking Swanson Channel in the Southern Gulf Islands, I can sometimes hear whales passing by. Most of the time it’s a pod of southern resident killer whales, hot on the trail of a school of Chinook salmon. In recent years, humpback whales have reappeared. Not in huge numbers, and they can’t be sighted daily, but they appear with a frequency and consistency that is encouraging. As with the more commonly observed orcas, you hear them before you see them. When humpbacks surface, they exhale, a frothy whooshing blast of air that sounds like someone trying to play a waterlogged tuba. The first time my daughter Meredith heard the telltale whoosh, she thought it sounded like a sea monster. We saw the tail flukes wave at us as the whale submerged and then we watched as it surfaced and submerged repeatedly, slowly moving away to the east.

In 2014, the government of Canada announced that it was down-listing the Pacific Ocean population of humpback whales from threatened to special concern. Great news, right? Instead of prompting celebrations about the recovery of a previously imperiled creature, the news provoked criticism and controversy. Environmentalists accused the government of down-listing humpbacks in order to smooth the waters for the proposed Northern Gateway project, which involves a new pipeline from northern Alberta’s bitumen sands to Kitimat on B.C.’s coast. From there, heavy crude would be loaded onto massive tankers, then navigated through a treacherous stretch of water where the Queen of the North ferry sank in 2006 and onwards to oil-thirsty consumers from California to China. The tanker route is a concern because it would pass directly through one of four areas identified by scientists as critical habitat for humpback whales.

Our predecessors treated humpbacks and other whales as nothing more than an infinite supply of natural resources, greedily hunting them for the oil their bodies contained. The Pacific humpback population that was once greater than 125,000 was decimated by the 1960s, with fewer than 10,000 remaining. When hunting was banned in 1966 under the auspices of a global treaty called the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling, humpbacks must have breathed a collective whoosh of relief. Their numbers slowly began to climb and are now estimated at more than 80,000, with steady annual increases of 4–5 percent.

The humpback’s cousin, the gray whale, was also nearly hunted into oblivion. Slurping sediments from the ocean’s floor and filtering amphipods and shrimp through their sieve-like baleen, gray whales grow to the bus-like size of 15 metres and 35,000 kilograms. Newborns are a mere five metres and less than 1,000 kilograms but grow rapidly. If those numbers seem too abstract to give you a sense of their immense size, try this: a gray whale calf drinks between 700 and 1,100 litres of its mother’s milk every day! In comparison, most human babies drink less than a litre of milk daily. Gray whales migrate from the Arctic waters of the Bering Strait to warm lagoons along the west coast of Mexico. That’s among the longest migrations of any animal in the world, an annual round-trip journey of between 16,000 and 22,000 kilometres.

On one of the most wonder-filled trips we’ve ever taken, my wife, Margot, and I went kayaking in Mexico’s Loreto Bay National Marine Park. We paddled from island to island in the Sea of Cortez on the inland coast of Baja California. The Sea of Cortez is like an enormous bowl of plankton soup, which explains why it is visited by as many as half of the world’s whale species. After hearing what sounded like a volcanic eruption, we saw several blue whales, the largest living creatures on Earth. The eruption was the sound of their exhalation as they came to the surface to breathe. Several days later, a fin whale, 70 feet long, swam directly beneath our kayaks, surfacing to our right so its dinner plate–sized eye could have a good look at us. We swam with pods of playful dolphins, which are lovely to watch but suffer from extreme fish breath when you get too close.

The highlight of our trip came after taking a bus across the Baja peninsula to Puerto López Mateos, a sleepy fishing village on the edge of the Pacific Ocean where the local pescadores seasonally hang up their nets and switch to ecotourism. Gray whales return each spring to the saltwater lagoons to give birth. The high salinity provides a boost, literally, to newborn whale calves who easily float at the surface of these protected waters.

A dark, blood-stained shadow hangs over these lagoons: tens of thousands of gray whales were slaughtered here during the whale oil era just decades ago. The species was nicknamed the devilfish because of their violent reaction to being harpooned and fierce defence of their calves. Gray whale populations were shattered.

And yet today, the gray whales are one of the most inspiring comeback stories in the natural world. Standing on the shore at Puerto López Mateos, we could see dozens. We hired a friendly fisherman to take us for a closer look in his panga, a 16-foot boat with a small engine. After motoring across the glassy water for about ten minutes, Jorge cut the engine, leaving us to bob and drift on the gentle tidal current. Within minutes, a gray whale calf, distinctive because its skin was smooth-looking and free of barnacles, approached the boat. With the brutal history of the area swirling through my mind, I was struck by this animal’s trust and innocence. The calf, glistening dark gray and the size of a Volkswagen van, swam right alongside our panga, which seemed to shrink in size. Jorge suggested we rub its head. This struck me as a bad idea. It was a wild animal, inherently unpredictable. And what about the stink of humans? Germs on our hands? What about conditioning it to approach people, not all of whom would be so friendly? Ultimately though, it was irresistible. The calf looked me in the eye and placed its head directly alongside the boat. I reached over the side and stroked its forehead. The skin was cool to the touch, but it felt like electric shocks coursed through my body. It was obviously sentient, intelligent . . . tears of joy sprang from my eyes. Then a full-sized, barnacle-encrusted gray whale, presumably its mother, gently nudged it away from the boat. We drifted around for a couple of hours on our gray whale meet-and-greet session. All the calves seemed curious and all the mothers protective. Some individual gray whales have lived 80-plus years, meaning they survived and may even remember the massacres that took place. It might sound flakey, but I felt a deep connection to those gray whales and they have left a magical and indelible memory.

In the mid-1930s, the League of Nations (the UN’s short-lived predecessor) adopted a ban on commercial hunting of several whale species in recognition of a rapid decline in whale populations. This ban was the first international agreement to protect whales. It wasn’t until 1982 that all commercial whaling was terminated by the International Whaling Commission, to enable populations to recover. Gray whales are still hunted by Indigenous people, subject to catch limits under the IWC’s Aboriginal subsistence whaling program. Several nations continue to hunt gray whales in defiance of international law, though in far smaller numbers than in the past. In 2014, the World Court ruled that Japan’s whaling program was illegal and that Japan’s excuse that it was conducting scientific research was unconvincing. With limited hunting, the remaining threats—collisions with vessels, entanglement in fishing gear, noise, and pollution—do not appear to threaten the survival of the species. Gray whales were removed from the U.S. endangered species list in 1994, as the population had recovered to between 25,000 and 30,000 individuals.

ROUTINELY VISIBLE FROM WHERE I SIT pecking away on the keyboard is a pair of bald eagles, perched atop a towering Douglas fir tree as though posing for National Geographic. Bald eagles are ubiquitous here on the south coast of British Columbia, making it difficult to imagine that when I was a young boy they nearly disappeared due to another act of human hubris. Unlike whales, it wasn’t hunting that endangered the eagles, but pesticides. The main culprit was DDT, which netted Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müeller a 1948 Nobel Prize in a classic example of premature congratulations. Between 1942 and 1972, a staggering billion pounds of DDT were used in the U.S. alone. The foolhardy application of pesticides that were never tested for potential adverse health and environmental effects prompted Rachel Carson to write her classic book Silent Spring (1962), warning of the deadly impact on birds. DDE, a compound formed when DDT breaks down in the environment, prevents normal calcium deposition when eggshells are forming. The thin-shelled eggs are then susceptible to breakage during the incubation period. Few chicks survived in this era. Bald eagles and other raptors were vulnerable to DDT/DDE poisoning because toxic substances bioaccumulate, or build up, in the food chain and these predators sit atop that chain.

Thousands of bald eagles were also shot during the 20th century, many in the belief that they would steal livestock. Although I have seen a bald eagle flying down the road on Pender Island with a chicken clutched in its talons, this kind of livestock predation is rare. Eagles are almost always scavengers. In 1782, the bald eagle became America’s national symbol over the objections of Benjamin Franklin, who preferred wild turkeys. Franklin felt eagles’ propensity for eating carrion reflected “bad moral character.” By the early 1960s, there were as few as 400 pairs of bald eagles nesting in the lower 48 states. Many states, from Nevada to New Hampshire, had no eagles at all.

The Migratory Birds Treaty signed by Canada and the U.S. in 1916 offered a modicum of protection from hunting, supplemented by 1940’s American Bald Eagle Protection Act, which prohibited killing or possessing eagles for commercial purposes. Bald eagles were formally declared endangered in the U.S. in 1967. Laws banning the use of DDT were enacted in the 1970s. Bald eagle chicks began to survive, and populations began to recover. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service down-listed bald eagles from endangered to threatened in 1995, and by 2007 they no longer required...

Table of contents

- The Optimistic Environmentalist

- Also by David R. Boyd

- Part I: The Big Picture

- Part II: Healthy Environment, Healthy People

- Part III: The Built Environment

- Conclusion: From Optimism to Action

- Selected Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Optimistic Environmentalist by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Ecología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.