eBook - ePub

About this book

Marx's Capital is back where it belongs, at the centre of debate about Marxism and its purchase on the contemporary world. In recent years there has been an explosion of much wider interest in Capital, after the debate on Capital largely fell silent in the late-1970s. In Deciphering Capital, Alex Callinicos offers his own substantial contribution to the debate. He tackles the question of Marx's method, his relation to Hegel, value theory and labour. He engages with Marxist thinkers past and present, from Gramsci and Althusser to Harvey and Jameson.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Composition

The Marx problem

The idea of someone who devotes their life to a work of art that turns out not to exist is a recurring one: it is, for example, the theme of Henry James’s short story ‘The Madonna of the Future’. In a very obvious sense this isn’t the problem with Marx. What we have is not the absence of a work, but a profusion of them. Enrique Dussel has written about the ‘four drafts of Capital’, but this is an underestimate.1 One can indeed identify the following economic manuscripts that form parts of the vast project that is best named by their recurring title or subtitle as Marx’s critique of political economy:

1 The Grundrisse, written between July 1857 and May 1858; first published in 1939

2 The so-called Urtext, fragments of a draft of the Contribution to a Critique of Political Economy, written between August and October 1858 and first published in 1941

3 A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, written between November 1858 and January 1859; published in June 1859 as ‘Part One’ of Marx’s intended Critique of Political Economy

4 The Economic Manuscript of 1861-63, written between August 1861 and July 1863 and intended as the continuation of the Contribution; published in part by Karl Kautsky as Theories of Surplus Value between 1905 and 1910 and in full only in 1982

5 The Economic Manuscript of 1863-5: Marx’s draft of the three volumes of Capital, written between July 1863 and December 1865; from this friend and collaborator Friedrich Engels edited Capital, Volume III, published in 1894; the so-called ‘Sixth Chapter’ of Capital, Volume I, ‘The Results of the Immediate Process of Production’, was published in 1933, and the entire manuscript in 1988 and 1992

6 Capital, Volume I, published in September 1867

7 Le Capital, the French edition of Capital, Volume I, published between 1872 and 1875 and increasingly treated as a separate text by scholars because of the substantial changes Marx made to it, not all of which were carried over into the second German edition (1873) or the third, published a few months after Marx’s death in March 18832

8 Smaller manuscripts written between the late 1860s and late 1870s in which Marx sought to address issues, particularly with respect to surplus value and profit, that he had broached in the 1863-5 Manuscript3

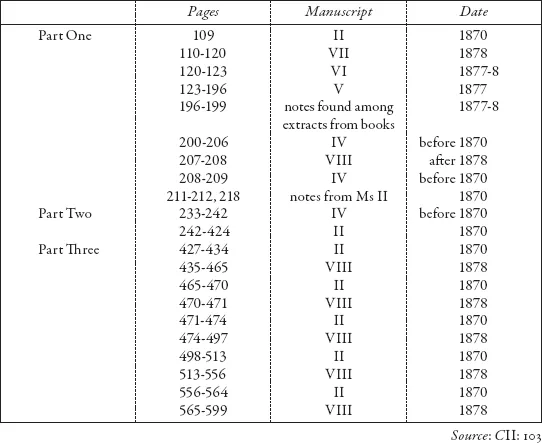

9 The manuscripts from which Engels edited Capital, Volume II (first published in 1885), which is a complex palimpsest of texts written at different times (see Table 1).

Table 1

Manuscripts from which Capital, II, was compiled (page references to Penguin edition)

Manuscripts from which Capital, II, was compiled (page references to Penguin edition)

The problem then with Capital is not so much that Marx laboured without result, but that his efforts were so vast and incomplete that his work dissolves into the multiplicity of fragmentary texts that he left behind. The immense achievement of MEGA2 in publishing the bulk of these manuscripts means that it is easy now for the apparently determinate structure of Capital to liquefy before our eyes. Dussel in his excellent study of the 1861-63 Manuscript expresses the view of a number of scholars:

It is well known that Marx only wrote Volume I (Book I) for publication. Hence, all the other volumes should be methodologically considered as non-existent and one should make references in the future, exclusively to the Manuscripts of Marx themselves. Engels and Kautsky’s editions (of Volumes II and III of Capital, edited in the 19th century, and the old Theories of Surplus Value) should be studied in order to know the thoughts of these two authors, but not Marx’s own.4

This is an extreme reaction, to which I return below when discussing Engels’s supposedly malign role in editing Capital, II and III. But in the meantime there is Marx himself to be dealt with. No one can dispute that, despite labours spanning more than 20 years, he left Capital unfinished. Michael Howard and John King in their outstanding history of Marxist economics take him to task for this:

In view of the central political importance that he assigned to the economic analysis of capitalism, Marx’s lethargy was most unfortunate. Even allowing for the effects of ill health, it is difficult not to convict him of neglecting his responsibilities, both to the international socialist movement whose mentor he aspired to be, and more especially to his lifelong friend Friedrich Engels, who was left to pick up the pieces.5

‘Lethargy’ is definitely not the right word. It is becoming increasingly clear thanks to the research conducted as part of MEGA2 that Marx continued to work intensively (although not always continuously because of the interruptions caused by political activity and ill health) till not long before his death. For example, in 1879-81, before the hammer blow struck Marx by his wife Jenny’s death in December 1881, he worked on world history, devoting five notebooks to the subject, which related to his efforts to broaden the scope of Capital.6

The problem rather is something much more mundane: Marx’s inability to finish anything, which was often accompanied by announcements of imminent completion. For example, he wrote to Engels optimistically on 2 April 1851: ‘I am so far advanced that I will have finished with the whole economic stuff in 5 weeks’ time. Et cela fait [And that done] I shall complete the political economy at home and apply myself to another branch of learning at the Museum’ (CW38: 325). The fact that he died nearly 32 years later leaving Capital unfinished is sometimes put down to his reaching some deep intellectual impasse. For example, Tristram Hunt speculates the problem might have been that ‘the economics of Das Kapital no longer appeared credible or the political possibilities of communism unrealistic’.7 Though Marx left behind him many unresolved problems, this kind of explanation is nonsense. His sometime Young Hegelian collaborator Arnold Ruge had identified the real problem as early as 1844, writing about Marx to Ludwig Feuerbach: ‘He reads a lot; he works with uncommon intensity and has a critical talent…but he completes nothing, he always breaks off and plunges anew into an endless sea of books’.8 Responding to Engels’s chivvying to finish Capital, I, Marx sought (31 July 1865) to make a virtue of his perfectionism: ‘Whatever shortcomings they may have, the advantage of my writings is that they are an artistic whole, and can only be achieved through my practice of never having things printed until I have them in front of me in their entirety’ (CW42: 173). The weary Engels replied rather crushingly (5 August 1865): ‘I was greatly amused by the part of your letter which deals with the “work of art” to be’ (CW42: 174).

The 1861-63 Manuscript, the most important of the recently published drafts, provides an excellent insight into Marx’s working method. He starts off as planned, writing a continuation of the 1859 Contribution: having dealt with the commodity and money in the two chapters of the earlier work, Marx now directly broaches ‘capital in general’. For nearly 350 pages he writes what is recognisably an early version of Capital, I, before breaking off in March 1862 midway through his analysis of relative surplus value and machinery to discuss theories of surplus value (presumably to mirror the procedure he used in the Contribution of critically examining the political economists’ treatment of value and money in respectively chapters 1, ‘The Commodity’ and 2, ‘Money’). But then, while discussing Adam Smith’s theory of profits, he confronts the problem of reproduction that will become one of the main subjects of Capital, II, and particularly the puzzle of how, in the circulation of commodities, the value of constant capital (invested in means of production) is replaced. Marx rather airily acknowledges that he has skidded off-piste: ‘The question of the reproduction of the constant capital clearly belongs to the section on the reproduction process or circulation process of capital—which however is no reason why the kernel of the matter should not be examined here’ (CW30: 414).

This first discussion of reproduction illustrates another of Marx’s tendencies, which is to think on paper, trying to resolve a problem by writing about it. Here (as elsewhere) this involves plentiful calculations before he reins himself in: ‘So much for this question, to which we shall return in connection with the circulation of capital’ (CW30: 449). Marx then dives into a discussion of the problem of productive and unproductive labour, which at least is related to Smith, before digressing out of chronological sequence for 40 pages on John Stuart Mill. Then it’s back to productive and unproductive labour, which slips into a further discussion of reproduction. At the end of this Marx acknowledges that he has not considered the case of extended reproduction (where the money generated by the cycle of production has to cover additional workers and means of production): ‘This intermezzo has therefore to be completed in this historico-critical section, as occasion warrants’ (CW31: 151). And then Marx returns to the chronology of his ‘historico-critical’ survey of the political economists, though not for long, since Marx inserts into the manuscript a ‘digression’ on the Tableau Économique of François Quesnay (leader of the 18th French school of Physiocratic economists), which greatly influenced the reproduction schemes in Capital, II, Part 3.

Although Marx then returns to the chronological track, he soon slides into his most fertile digression, on the theory of rent. This was apparently prompted by the German socialist leader Ferdinand Lassalle’s request in June 1862 that he return the book on rent by the Ricardian economist Johan Karl Rodbertus that Lassalle had lent Marx (see Marx to Lassalle, 16 June 1862: CW41: 376-9). The result was what Dussel calls ‘the central moment of all the Manuscripts of 1861-63’, and ‘the beginning of the confrontation with Ricardo’.9 As we explore in more length in the next chapter, ground rent is an obvious anomaly for the labour theory of value, since the landowner obtains a revenue thanks merely to the ownership of a material asset without making any productive contribution. Ricardo in his Principles sought to solve the problem through the theory of differential rent, which explained rent by differences in the productivity of labour on different pieces of land. But he denied the existence of absolute rent that arises even on the poorest patch of land. Marx devotes over 300 pages to solving this problem, in the course of which he reformulates the labour theory of value, drawing his fundamental distinction between the values of commodities, the socially necessary labour time required to produce them, and their prices of production,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Guide to citations

- Introduction

- 1 Composition

- 2 Method,I: Ricardo

- 3 Method, II: Hegel

- 4 Value

- 5 Labour

- 6 Crises

- 7 Today

- Appendix: Althusser’s Detour via Relations

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Deciphering Capital by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Economic Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.