![]()

1 A Sting in the Tale

If only one thing is known about wasps, it is that they sting. The pain may vary from a puzzling pinprick to a howl-inducing hot dagger stab and it may fade in moments or remain a flesh-numbing throb that aches for days. A sting, though, is usually just a minor inconvenience – a personal measure of the sensitivity of human skin. The welt, if one appears, is a trivial wound, but the power of the wasp’s venom, and the seeming tenacity of their attacks, marks out these otherwise insignificant creatures as dangerous and vengeful. However, wasps are less dangerous than honeybees; and hornets (an epithet reserved for the largest of wasps) are unfairly labelled with a curmudgeonly disposition they do not possess. The sting in the tail of a wasp has elevated what is in effect a tiny insect into a monster of phantasmagorical proportions. Yet, as with so many human anxieties, this is a fear based on ignorance – in reality there is no such thing as monsters.

The sting did get wasps noticed, though, and our ancestors soon gave these specks of painful animosity a name. The simple common English name ‘wasp’ is clearly derived from the Latin vespa, a term still used in the scientific literature as the generic name for hornets. Likely their colloquial nickname ‘jasper’ also came from here. This root is expanded into myriad similar names in other European languages – Wespe in German, wesp in Dutch, hveps in Danish, veps in Norwegian, avispa in Spanish and guêpe (formerly guespe) in French. In early English writings it was sometimes distorted to wops or wapse – perhaps illiterate misrenderings or childish jumblings.

The trouble is that our ancestors were not expert insect taxonomists and there has been a constant muddle over any small creature that stings, bites or just buzzes around looking a bit menacing. The modern word hornet comes from Old English hyrnet (also harnette, hyrnitu, hyrnet), and is thought to be somehow linked with horn, but whether this was for its tough orange-brown carapace or a loud buzzing vuvuzela sound is uncertain. Perhaps it rests on the hornet’s reputation for aggression, as in the splendid archaic phrase ‘horn-mad’ – enraged, like an angry horned bull. In Dutch horzel can mean hornet, but it is also used for horse flies (large blood-suckers in the fly family Tabanidae) – unpleasant and off-putting, maybe, but a completely different group of insects. The Welsh for wasp is variously given as kakkyman, cacynen, nghacynen alongside various other dialectical variants, and also gwenyn meirch, which is literally ‘horse bee’. Common or vernacular names are often fraught with difficulty.

The earliest depictions of wasps are in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs from 5,000 years ago,1 but any entomologist will look askance at these crude stone engravings and wonder whether the designs are wasp, hornet or (most likely) honeybee – a confusion that still reigns today. The stylized insect carvings are not helped by the frequent depiction of only four legs – hardly an endorsement of the ancient artist’s credibility when it comes to anatomical accuracy. Aristotle had a reasonable knowledge of some wasps, and he makes many astute observations. He knew there was a mother (or ‘leader’) wasp in the nest (just like in honeybee hives), larger and gentler than the run-of-the-mill workers; he knew that these could hibernate over winter ‘lurking in holes’, but he seemed uncertain whether they could sting (they can). But 2,000 years of linguistic and scientific reinterpretation leaves many shadows and it is often unclear what types of insect he and his contemporaries were really describing in their various texts. He used many names like Sphex, Crabro (supposedly after the town Crabra in Tusculanum where they were abundant), Agrion and Anthrene (so called because the sting raised a carbuncle or anthrar, a variant of anthrax).2 Some of these names are today reused for completely different organisms – Sphex and Crabro are now genera of small solitary wasps, but Agrion refers to a group of delicate (and non-stinging) dragonflies. Anthrenus is now the carpet beetle of domestic pest fame; although from the same root the similar Andrena is used for a broad group of small solitary bees – though whether their stings are powerful enough to raise a carbuncle in the flesh is very doubtful.

From an intricately carved ancient Egyptian stone facia, a hieroglyphic winged insect – but whether wasp or honeybee is still open to debate; wing and leg number do not help in the identification.

This confusion is not helped by the fact that the concept of wasp still has a sometimes vague and nebulous fluidity. Just like the ‘fly’ in butterfly and dragonfly, which are patently not flies, the title ‘wasp’ is applied almost haphazardly to a whole host of different creatures. Despite advances in scientific understanding, modern entomologists have not always assisted. To start, then, it is important to work out exactly what we mean by ‘wasp’.

WHAT MAKES A WASP?

Broadly speaking, wasps belong to the hyperdiverse insect order Hymenoptera, from the Greek, humeno pteros, meaning ‘membrane-winged’. Wasps have four clear membranous wings, unadorned by the colourful scales of butterflies and moths. As hieroglyph carvers discovered, wasp wing number is sometimes difficult to appreciate – front and back wings are coupled together by a row of microscopic hooks, the hamulus, linking them into a unified aerofoil. The Hymenoptera is clearly a natural insect grouping; it includes the honeybees, bumblebees and ants, and a vast array of tiny or obscure creatures which never quite acquired helpful or usable common names. The problem is that, with the exception of a very small number of bees and ants, almost all of the insects in the Hymenoptera (something in the order of 250,000 species worldwide) are now also, quite legitimately, called ‘wasps’ by expert and non-expert alike.3

The smallest free-living insects (body lengths down to 0.139 mm), which parasitize insect eggs, are called fairy wasps for their pale flimsy appearance. The small ant-like insects that develop inside bizarre plant growths like oak apples and marble galls are called gall wasps. The slim, but often large, parasitoids that lay their eggs in caterpillars (the hatching maggots consume their victim, alive, from the inside) are routinely called ichneumon wasps – an ancient Greek coining, meaning ‘tracker’. Elsewhere there are plenty of other wasps: potter wasps make small vase-shaped cells of mud in which they place paralysed insect prey for their grubs; mason wasps dig small burrows into lime mortar between old brickwork; fig wasps, tiny ant-like insects, specialize in fertilizing fig flowers; sabre wasps are large but slim insects with frighteningly long, sword-like tails; wood wasps are named for the giant intimidating adults and wood-boring grubs. Wasps, it seems, come in all shapes and sizes. No wonder people are baffled.

Despite this potential confusion, simplicity can still be brought to bear. The wasps buzzing around the remains of a cream tea are mostly easily identifiable to one particular insect group. In scientific terms they belong to the hymenopteran family Vespidae,4 typically in the genera Vespa, Vespula, Dolichovespula or similar, and are described by entomologists as social wasps, or in North America in particular as yellow-jackets. Alongside these are the so-called paper wasps, Polistes, rather slimmer and longer-legged than yellow-jackets; they are named for their small papery nests, although as it turns out all vespids make nests from paper. In the British Isles there are currently ten species in this group, in Europe twenty species, twenty in North America and about 4,000 across the globe. These vespid hymenopterans now give us a focus, and the Wasp of this book’s title.

Despite narrowing down the wasp concept to a manageable bookful, there is still every chance to stumble. Many a tabloid picture editor has fallen foul of expected taxonomic rigour by choosing an inappropriate image of a bee or fly, or one of those many non-vespine hymenopterans to match the carefully crafted nonsense about wasp plagues, foreign super-stinger invaders and bee-killers. So, for their benefit, at least, here are some further guidelines on what exactly a ‘true’ wasp looks like.

Within the insect order Hymenoptera, wasps (along with bees, ants and many of those parasitic ichneumons) are placed in the suborder Apocrita, from the Greek (apokrisis), meaning separated. Members of this large suborder have a narrow wasp-waist clearly separating thorax and abdomen (the petiole in entomological jargon), a structural feature that will later be personified in the extreme corsetry of Victorian women’s fashion. This cutting-in of the narrow waist meant that wasps were sometimes referred to as ‘cut-wasts’ or, more tellingly, ‘cut-wasted vermine as are winged’.5 This narrow, sometimes stalk-like hinge allows the insect the most supreme flexibility in pointing its sting-tipped abdomen in almost any direction it likes – left, right, upwards or curled down underneath its body and pointing forward between its legs. This is especially helpful when the wasp is grappling with then paralysing its chosen caterpillar victim, or killing its insect prey. Picked up in animal paw, bird beak or between human finger and thumb it can use its manoeuvrability to manipulate its venomous tail and stab its attacker in the nearest available soft spot. Ouch.

The Apocrita is further subdivided, and within it the familiar assemblage of bees, wasps and ants are gathered into a natural evolutionary group – the Aculeata. This is an old and well-worn name deriving from the insect’s obviously acutely pointed tail end, usually tipped with that familiar painful sting – the Aculeus of scientific textbooks.6 Structural, behavioural and genetic similarities show these groups of insects to be intimately related, and clearly derived from a common ancestor dating to around 175–200 million years ago (MYA). To date, compression fossils, from Jurassic silt deposits in Central Asia, from perhaps some 150 MYA, contain what are thought to be the most ancient putative Aculeates.7 These small insects from the extinct family Bethylonymidae have simple wing venation and slim ant-like bodies and seem closest to the modern family Bethylidae. There is no accepted common name for this obscure group of tiny insects, but they have short stings with which they subdue their prey. Fossils (in stone and in amber) recognizable as belonging to the modern lineages of bees, ants and wasps date from the early Cretaceous – about 135 MYA. The oldest known apparent true vespine wasp fossil appears to be Palaeovespa baltica from Baltic amber, calculated to be about 30 million years old.8

Ants seem relatively distinct from wasps. They are generally small and rather ant-like, with large triangular head, narrow thorax and bulbous abdomen. Worker ants’ lack of wings makes their identification easy, but flying ants (winged males and queens) can sometimes be disconcertingly wasp-like. However, few ants are large or brightly coloured black and yellow. Confounding some wasps and bees, though, is a mistake still made even by expert naturalists.

The most straightforward distinction, but perhaps the one most difficult to discern from a photograph or a museum specimen, is that bees are wholly vegetarian – they and their larvae feed solely on carbohydrate sugary nectar and protein-rich pollen. This simple fact of ecology is partly at the root of the cult of honey, that magical sweet liquor that has fascinated and fixated humans for millennia and made bees the heroes that wasps are not. Bees are valued as pollinators and their earnest, businesslike diligence and industry further cements their good reputation. Wasps, on the other hand, are primarily predatory. Though they might sometimes visit flowers for a bit of nectar and fallen fruit for juices, they must catch and kill insect prey to feed to their wholly carnivorous grubs back in the nest. They are not above ripping bits of decaying flesh from carrion, and will also scavenge gristly remnants from animal scats – all behaviours likely to alienate them further. There is a bizarre tale of wasps apparently chewing off small portions of live pigs’ ears in the farmyard, and Canadian entomologist John Phipps claimed blood-stained Kleenex evidence when one chewed his ear (‘fairly painful’) before making off with a droplet of his blood.9 Bees would never do anything as vulgar as this.

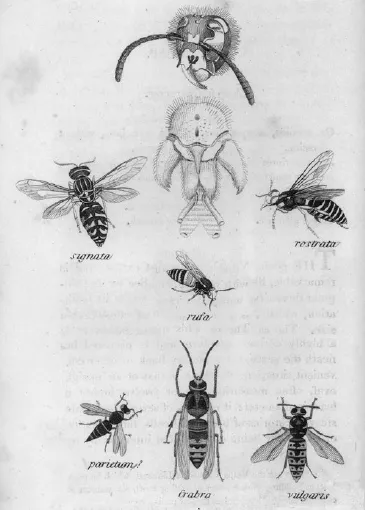

Selection of wasps, including the common wasp (Vespa vulgaris), hornet (Vespa crabro), red wasp (Vespula rufa) and one of the solitary mason wasps (Ancistrocerus parietum). From George Shaw and Frederick Nodder, The Naturalist’s Miscellany (1810).

Structurally there are several very subtle differences between bees and wasps, but caution and a microscope are usually required to discern them. Colours and patterns are useless, with ...