![]()

1 Ways of Thinking about Glaciers

A perennial mass of ice, and possibly firn and snow, originating on the land surface by the recrystallization of snow or other forms of solid precipitation and showing evidence of past or present flow.1

Today, from a distance, I saw you

walking away, and without a sound

the glittering face of a glacier

slid into the sea.2

Precisely defined for the scientist, a metaphor and an icon for the poet, glaciers for each of us have their own place in our view of the world.

Human life has developed in an unusual period of Earth’s history: a period in which there are glaciers. Of the history of the planet, glaciers have been here, on and off, for only about 15 per cent of the time, but they have been here throughout the 2 million years of human history and prehistory. However, only for the last century have we lived in an age in which the importance of glaciers has been acknowledged. It is less than two hundred years since the idea was first widely accepted that ice ages come and go, and that glaciers used to cover much more of the Earth’s surface than they do now. We have only just noticed that we are living in a glacial period. We live now, for the first time, in a cultural ice age as well as a physical one. Few of us consciously place ‘glacier’ at the heart of our view of the world but we do now appreciate the key role of glaciers both in the planet’s past – creating the landscapes that surround us – and in its future, as major players in the unfolding drama of climate change. But at the same time that we noticed glaciers we also realized that the physical ice age may be coming to an end, that we are losing the glaciers, and that it may be our fault that we are losing them so fast.

Because we recognize the importance of glaciers in the global system we now have a particular view of the world, different from that of the generations before us. In glaciers we recognize nature’s fragility, complexity, majesty, ephemerality, vastness, beauty, terror: in glaciers we see the sublime. Each of us is also touched by them very directly on a practical day to day level, wherever on the planet we live. Glaciers created my local English landscape, determining the nature of the soil and of the crops that grow here, but they also control the atmospheric and ocean circulations that drive weather systems across the globe. They influence sea level in every ocean, and they supply drinking and irrigation water to millions of people. Glaciers are not remote: they reach out to touch everything, everywhere. On the other hand, especially to lowland, mid-latitude city dwellers, the glacier is an alien creature whose name conjures images of wilderness, frozen wasteland and polar desert.

The way you think of glaciers depends on where you live, and when. At the Siachen Glacier, which reaches an altitude of 5,753 m (18,875 ft) on the disputed border between India and Pakistan, more than a thousand soldiers have died in recent decades in a long-running conflict waged at such a high elevation that far more casualties have been caused by avalanches and altitude-related illness than by gunfire. In 2012 an avalanche killed 129 Pakistani soldiers on the glacier. But the Siachen Glacier and its forgotten war do not feature prominently in the international headlines. For the vast majority of people, glaciers are far away or long ago. Most people have never seen a glacier. Glacier historian Mark Carey observed that some visitors looking up at the mountains in Glacier National Park in Montana, USA, cannot even recognize a glacier when they first see one.3 By contrast, in some places glaciers play a major role in everyday life and in cultural history. There is a rich tradition of folk stories, myths and legends running through popular culture in the European Alps, and the Icelandic sagas are replete with glaciers and glacial meltwater floods. If you grew up with glaciers, live with glaciers, and live in a culture rich in glacier mythology then you see them in a certain way. Anthropologist Julie Cruikshank, writing about the indigenous peoples of Alaska and the Yukon, describes their tradition of incorporating nature within human affairs:

Land, ice and ocean: glacier ice meeting the coast in Antarctica.

Glacier exotic: glacier-clad mountains of the Altai Range in Mongolia.

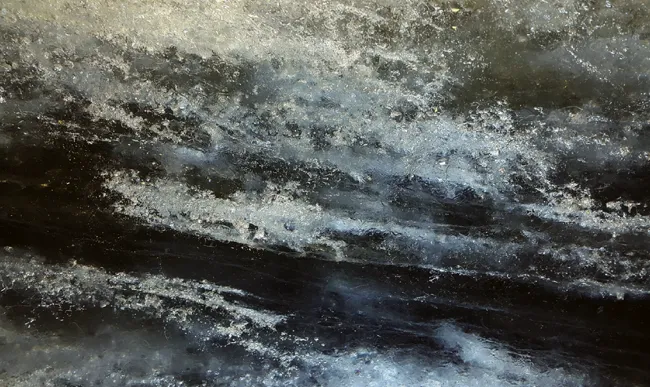

Close-up image of ice in a glacier, showing areas of clean ice (dark) and areas with air bubbles (light).

In . . . Athapaskan and Tlingit oral tradition, glaciers take action and respond to their surroundings. They are sensitive to smells and they listen. They make moral judgements and they punish infractions. Some elders who know them well describe them as both animate (endowed with life) and as animating (giving life to) the landscapes they inhabit.4

Today glaciers are most frequently encountered in popular culture under the heading of environmental protection. By contrast, for a period of several hundred years up until the mid-1800s glaciers were advancing in many parts of the world, causing devastating floods and avalanches, wiping out settlements and overwhelming populated areas. Brian Fagan called a chapter in his book about that period ‘The War against Glaciers’.5 It seems to be a war that we now regret having won so convincingly. Glaciers are disappearing from mountain tops around the world, causing a new set of environmental hazards and cultural changes.

From traditional to Romantic

Folk tales involving glaciers have been reported from many different locations. In the Ecuadorian Andes traditional stories explain the ice-capped peaks in terms of interrelationships between mythical characters represented by the mountains.6 When the summit of Cotacachi is covered in snow, for example, one story tells us that it is a sign that her lover Imbabura (a neighbouring volcano) has visited in the night. When asked about climate change and the loss of ice from the ‘darkening peaks’ younger people with formal education talk about climate change, but older people refer back to events in traditional stories, and attribute the changes to Cotacachi’s ‘punishment’. Different cultures, and different generations within the same culture, have different points of view. This contrast between tradition and enlightenment, between magic and science, can be traced back into the seventeenth century, as scientific explorers and Grand Tourists exported European attitudes and methods. The age of enlightenment, the age of romanticism, the age of exploration, the age of exploitation, the age of environmental conscience . . . wave after wave of re-visioning of landscapes.

The Grinnell Glacier Trail, in Montana’s Glacier National Park. The park’s glaciers are retreating catastrophically, but the spectacular glacial landscape remains.

In Europe before the age of enlightenment glaciers were viewed most commonly as remote, menacing and fearsome: an obstacle and a threat. Glaciers were associated with areas beyond the reach of civilization or law, with bandits, avalanches and wild country. In this period glaciers were also an increasing menace: an advancing threat. During a period known as the ‘Little Ice Age’ between about the fourteenth century and the end of the nineteenth century glaciers across Europe and in other parts of the world experienced substantial advances. Land was lost beneath expanding glaciers, and damaging floods occurred when advancing ice temporarily blocked rivers, impounding lakes which subsequently burst with devastating effects.

This picture from about 1903 shows a group of tourists on the Mer de Glace, Chamonix.

By the end of the seventeenth century a new layer of subtlety was entering into European perceptions of glaciated and wilderness landscape. Increasing numbers of people were travelling through the Alps, many of them taking the ‘Grand Tour’ through Europe to the classical sites of Italy. En route they would pass through wild Alpine scenery, but would experience it from the perspective and with the physical and economic security of wealthy aristocracy. Today’s equivalent, perhaps, is the ‘Glacier Express’ tourist railway, which runs between Zermatt and St Moritz and is described in its promotional literature as ‘indescribably beautiful’ for its ‘roaring mountain streams and craggy cliff faces’. For the Grand Tourist, as today for the rail traveller, the ‘fearful’ landscape was, although close at hand, made safe to a level where the ‘danger’ could actually be enjoyed. Eighteenth-century philosophers such as Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant developed the idea of the sublime to describe this feeling where the observer of wild and fearful nature might experience a quite pleasurable sensation from recognizing (at a safe distance) the overpowering strength of nature and our own insignificance. This idea flourished with the development of the Romantic movement in art and literature. Wilderness landscapes, mountains and glaciers, storms at sea and other natural terrors were presented by artists such as Turner and poets such as Wordsworth as evidence of nature’s wild glory. As exploration of remote areas progressed, and civilized tourism penetrated further into formerly inaccessible areas, locations that could still be considered extreme wilderness and inspire sensations of the sublime became more and more remote. By the end of the nineteenth century the Alps were no longer sufficiently extreme to engender adequate feelings of danger and awe in the popular imagination, and the polar regions started to take their place as the focus of our shared image of the ultimate fearful wilderness, our shared sublime.

The Glacier Express en route to Zermatt.

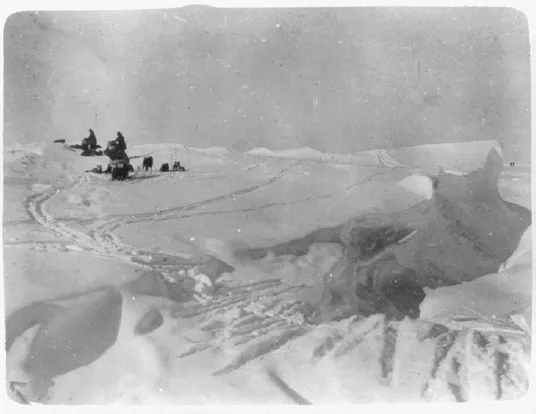

This photograph from Roald Amundsen’s 1910–11 Antarctic expedition was titled ‘A striking view at the top of the Devil’s Glacier, looking toward Hell’s Gate’.

The great polar explorations of the early twentieth century were founded in a fortunate coincidence of interest in exploration, imperialism and romantic adventure. The diaries and reports of Scott, Shackleton and others are self-consciously epic-heroic, clearly aware of the significance, quite beside all the science and discovery, of pitting humanity against the wilderness. The names of their ships set the tone: Scott sailed in the Discovery, Shackleton in the Endurance. Nansen sailed in the Fram, which is Norwegian for ‘Forward’. The names of the features that they encountered and the role of glaciers as obstacles to progress have entered the language of popular culture. The Ross Ice Shelf is known as the Great Barrier. The Beardmore Glacier features prominently in Scott’s diaries as a barely surmountable threshold to the polar plateau. Later in the century, the Khumbu Icefall on Everest, at the head of the Khumbu Glacier above base camp on the way to the summit, has taken on that same ‘barrier’ iconography – glacier as something to be crossed, surmounted, overcome on the way to a greater prize; glacier as fearful challenge; worthy adversary.

Science to the forefront

Scott’s Antarctic expedition was about not only exploration and adventure, but science. Through the twentieth century right up to the present, as opportunities for genuine exploration of new territory have diminished, adventurous expeditions into wilderness areas, whether genuinely motivated by science or in fact primarily adventure trips, have usually been at least partially justified by some scientific content. Even teams of schoolchildren taking trips to Iceland or Alaska seem to have to validate their requests for financial support with some claim to be ‘doing science’. By the start of the twenty-first century, glaciers in popular imagination had become synonymous with concerns about global warming and were easy pickings for anybody to do some simple science in the context of environmental change. Glacier science has been closely involved in our developing understanding of climate change for nearly two hundred years. In the 1840s, Swiss scientist Louis Agassiz began to convince the geological community of what several people had already noticed: that glaciers used to be much more extensive in the past, and that this must have been associated with an ‘ice age’. If there was an ice age in the past, and glaciers had ...