eBook - ePub

Scripture and Its Interpretation

A Global, Ecumenical Introduction to the Bible

- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Scripture and Its Interpretation

A Global, Ecumenical Introduction to the Bible

About this book

Top-notch biblical scholars from around the world and from various Christian traditions offer a fulsome yet readable introduction to the Bible and its interpretation. The book concisely introduces the Old and New Testaments and related topics and examines a wide variety of historical and contemporary interpretive approaches, including African, African-American, Asian, and Latino streams. Contributors include N. T. Wright, M. Daniel Carroll R., Stephen Fowl, Joel Green, Michael Holmes, Edith Humphrey, Christopher Rowland, and K. K. Yeo, among others. Questions for reflection and discussion, an annotated bibliography, and a glossary are included.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Scripture and Its Interpretation by Gorman, Michael J., Michael J. Gorman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Criticism & Interpretation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

The Bible

In part 1 of this book, we orient you to the Bible as a whole, its geographical and historical contexts, and the contents of the two Testaments. We also introduce you to some important nonbiblical writings, the formation of the Bible (the canon of Scripture), and the transmission and translation of the Bible over the centuries.

In addition to this book, a good study Bible prepared by a team of scholars is a helpful resource. Some options for readers of English include the following:

Attridge, Harold W., ed. The Harper Collins Study Bible. Rev. ed. New York: HarperOne, 2006. New Revised Standard Version (NRSV).

Berlin, Adele, and Mark Zvi Brettler, eds. The Jewish Study Bible. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. New Jewish Publication Society translation (NJPS) of the Hebrew Bible (Christian Old Testament).

Carson, D. A., ed. NIV Zondervan Study Bible. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2015. New International Version (NIV).

Green, Joel B., ed. The CEB Study Bible. Nashville: Abingdon, 2013. Common English Bible translation (CEB).

Harrelson, Walter, ed. The New Interpreter’s Study Bible. Nashville: Abingdon, 2003. New Revised Standard Version (NRSV).

Levine, Amy-Jill, and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds. The Jewish Annotated New Testament. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Senior, Donald, John Collins, and Mary Ann Getty, eds. The Catholic Study Bible. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. New American Bible translation (NAB).

Each chapter in this book concludes with a list of recommended reading for further study. Other general recommended resources for serious biblical study include the following.

One-Volume Resources

Freedman, David Noel, ed. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000. A one-volume Bible dictionary with almost 5,000 contributions from more than 600 scholars.

Muddiman, John, and John Barton, eds. The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. A one-volume collection of commentaries on all the biblical books.

Patte, Daniel, ed. Global Bible Commentary. Nashville: Abingdon, 2004. A one-volume commentary on both Testaments, with contributions from scholars around the world.

Vanhoozer, Kevin J., ed. Dictionary for Theological Interpretation of the Bible. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2005. Biblical, theological, and interpretive articles.

Multivolume Resources

Keck, Leander E., ed. The New Interpreter’s Bible. 12 vols. plus an index volume. Nashville: Abingdon, 1994–2004. General articles on various aspects of the Bible precede extensive commentaries for each biblical book that include theological reflection on every passage.

Sakenfeld, Katherine Doob, ed. New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible. 5 vols. Nashville: Abingdon, 2006–2009. In-depth articles on everything related to the Bible and biblical study.

Electronic Resources

Among the most sophisticated programs for biblical studies, the following generally come in various packages: Accordance, BibleWorks, Gramcord, and Logos.

1

The Bible: A Book, a Library, a Story, an Invitation

The title of this book contains within it two ways of referring to its subject matter: Scripture and the Bible. The first, Scripture, sometimes used in the plural (the Scriptures), comes from the Latin for “writings” (scriptura); this in turn corresponds to a common way of referring to sacred writings in Greek: hai graphai (the writings). The second, Bible, comes from the Greek word for “book,” biblion. What we are about to explore, then, is a book, or collection, of sacred writings. For this reason, people of faith sometimes call this book the Sacred Scriptures or the Holy Bible.

Although many people use the terms “Bible” and “Scripture” interchangeably, as we will here, the two terms can suggest different nuances of meaning. For instance, many religious traditions have sacred texts, or scriptures, but only Judaism and Christianity refer to their scriptures as “the Bible.” Ironically, however, some people feel that the term “Bible” is more religiously neutral, and perhaps more academic, than the term “Scripture,” with its connotation of holiness or divine inspiration. In fact, this situation is now so commonplace that some biblical scholars, including many contributors to this book, insist that when we interpret the Bible from the perspective of faith, even from an academic point of view, we are treating it as Scripture, as sacred text—not merely as ancient literature.

In this and the following chapters, we will attempt to look at the Bible, or Scripture, from both an academic perspective and a faith perspective. That is to say, we want to understand it, simultaneously, as both human book and sacred text.

Our investigation begins with a consideration of the Bible as both book and library, and then, more briefly, as both story and invitation.

The Bible as Book

As we have just explained, the English word “Bible” originated from the Greek term for book (biblion), which is derived in turn from the Greek words for the papyrus plant (byblos) and its inner bark (biblos). Egyptian craftsmen produced an ancient version of paper by matting together strips of this marshland plant. The dried sheets of papyrus were then glued together in rolls to become a scroll. Jeremiah, especially in its ancient Greek version (the Septuagint, abbreviated LXX), gives a colorful example of how the invention of these materials contributed greatly to the development of the Bible:

In the fourth year of King Jehoiakim son of Josiah of Judah, this word came to Jeremiah from the LORD: Take a scroll [Greek chartion bibliou] and write on it all the words that I have spoken to you against Israel and Judah and all the nations, from the day I spoke to you, from the days of Josiah until today. (Jer. 36:1–2 [43:1–2 LXX])1

Baruch, Jeremiah’s secretary, refers to the process: “He dictated all these words to me, and I wrote them with ink on the scroll [Greek en bibliō]” (v. 18). Even though the angry king burned the document “until the entire scroll was consumed in the fire” (v. 23), Jeremiah dictated another with “all the words of the scroll that King Jehoiakim of Judah had burned in the fire, and many similar words were added to them” (v. 32). From this biblical passage, it is relatively easy to understand the transition from writing on papyrus (Greek biblos) to naming the finished product, a scroll or a book (Greek biblion).

Ordinarily, only one side of a papyrus scroll contained writing. (The heavenly visions in Ezekiel and Revelation specifically mention writing on both sides of the papyrus as a sign of an extraordinary, supernatural message: Ezek. 2:10; Rev. 5:1.) Scrolls were the ordinary instrument for preserving and reading the sacred texts in synagogues; locating a particular passage required some dexterity with large scrolls. The Gospel of Luke describes the scene in the Nazareth synagogue when “the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was given to [Jesus]. He unrolled the scroll and found the passage where it was written: ‘The Spirit of the Lord is upon me . . .’” (4:16–17).

Papyrus was not the only material on which ancient writers inscribed texts. After animal skins were thoroughly cleaned, stretched, dried, and stitched together, they served the same purpose as the more costly papyrus, which grew only in certain lowland regions (e.g., Egypt, Galilee) and thus often had to be imported. The abundance of sheep and goats in Palestine provided a steady source of durable scrolls called parchment (Greek membrana). Scribes who produced the collection of Jewish manuscripts (from around the time of Jesus) that scholars today call the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) used these animal skins, which were durable enough to survive after more than 1,900 years in clay jars.

In Roman times, writing tablets with wax surfaces were framed and hinged together along one edge. Since the frames were made of wood (Latin caudex), the set of writing tablets was called a codex. This arrangement allowed for writing on both sides. Soon sheets of papyrus or parchment were sewn together at the spine. The result was the precursor of the modern book. By the second century CE,2 the emerging books of the Christian canon (a collection of authoritative sacred texts) were inscribed in this kind of codex, while the Jewish community generally retained the scroll format. The practicality and economy of a portable document with writing on both sides were eminently suited to the rugged missionary lifestyle of Christian evangelists, and the codex helped Christians to think of their various sacred texts as constituting one book.

The Bible as One Book

Most people come to the reading of the Scriptures with some preconceptions about what they are. Since they are often described by one, singular title—“the Bible”—and since, like most other books, the Bible has a front and a back cover, it is understandable that so many people think of the Bible simply as one book. A quick glance at the titles in a Bible’s table of contents might give the impression that it is one book with many chapters. Likewise, believers confidently speak of the whole Bible as the “Word of God.” This familiar heartfelt expression of faith significantly reinforces the idea that God is the one author of everything contained in its unified pages. And to be sure, the Bible does tell one grand story of God’s love for humankind, which theologians have tried to summarize in such biblical words as grace, salvation, the kingdom of God, or covenant. (We shall return to this story toward the end of the chapter.)

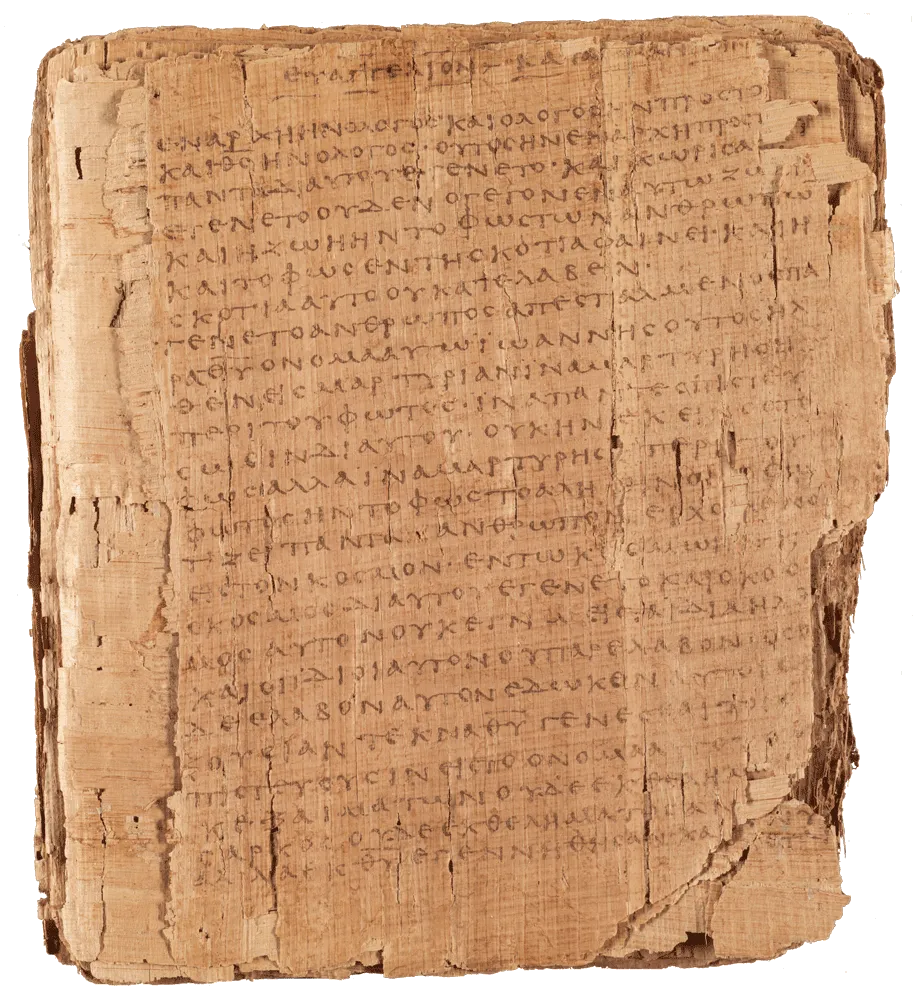

Figure 1.1. The first page of the Gospel of John from P66 (Papyrus Bodmer II), the earliest relatively complete manuscript of that Gospel, dating from ca. 200 CE. [Martin Bodmer Foundation in Cologny (Geneva)]

However, even after spending only a little time paging through the dozens of individual sections of the Bible, we discover great diversity in writing style and content, suggesting many different human authors and objectives. In addition, the dates implied in these texts range from the beginning of the world to what seems like its end in the not-too-distant future. This variety of historical epochs suggests long periods of use and reinterpretation of earlier documents.

Honestly recognizing the complexity of the Bible as a diverse collection prepares us to experience both why it is a treasure of great spiritual value and why it also requires careful study. In fact, the Bible attests to its own diversity.

The Bible as Many Books

The Bible clearly indicates that it contains other books within itself. Frequently, the Bible refers to the “book of the law of Moses” (2 Kings 14:6) or the “book of Moses” (Mark 12:26). Mention is also made of other specific documents, such as the “book of the words of the prophet Isaiah” (Luke 3:4; cf. 4:17), the “book of the prophets” (Acts 7:42), the book of “Hosea” (Rom. 9:25), and the “book of Psalms” (Acts 1:20).3

The Gospel of John also refers to itself as a “book” (John 20:30; Greek biblion). Likewise, the author of the Acts of the Apostles tightly knits that document to the story about Jesus that the same person had presented “in the first book” ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Endorsements

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part 1: The Bible

- Part 2: The Interpretation of the Bible in Various Traditions and Cultures

- Part 3: The Bible and Contemporary Christian Existence

- Glossary

- Scripture Index

- Subject and Author Index

- Back Cover