![]()

CHAPTER ONE

A WONDERFUL FISH

If you believe such things, there’s a beast that does the bidding of

Davy Jones. A monstrous creature with giant tentacles that’ll

suction your face clean off, and drag an entire ship down to the

crushing darkness. The Kraken…

—PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN

n October 26, 1873, Theophilus Piccot and an assistant known to history as Daniel Squires rowed out for herring over the icy-cold surface of Portugal Cove in Newfoundland’s Conception Bay. Piccot knew the bay well. He had fished these waters hundreds of times. But on this trip, he and Squires saw something unusual floating in the distance below the Newfoundland cliffs.

It was quite large.

It looked, at least from a distance, something like an abandoned sail or debris from a wreck.

Hoping for valuable salvage, they rowed over. The two men found a quivering mass unlike anything they’d ever seen. They poked the mass with a gaff. It was a living creature. It reared its beak at them, which the men later said was “as big as a six-gallon keg.” The animal’s beak rammed the bottom of their skiff. From its head shot out “two huge livid arms.” The animal then began to “twine” its arms around the boat.

The two feeding tentacles, several times the men’s height and covered with serrated rings inside the suckers, shot out over the gunwales of the skiff, seeming to move with the speed of a lightning bolt. Fortunately, Piccot had a hatchet on board. He hacked away. He severed both tentacles, as thick as his muscular wrists, from the rest of the creature. The animal shot out gallons of ink which “darkened the water for two or three hundred yards.” Then it sped away as the men watched. It was never seen again.

Piccot and Squires returned to port in St. John’s, bringing with them what might well be one of the world’s best-ever fish stories. They also brought back both severed organs, which had begun to stink almost unbearably. One they destroyed, not knowing its scientific value.

The other was saved by the local rector, who received the flesh as though he had received the stone with the Ten Commandments. Moses Harvey, like so many educated Victorians, was an amateur naturalist. He had followed the decades-long scientific controversy over the existence of a fabled sea monster. He may well have read, only months earlier, a paper by A. S. Packard published in The American Naturalist arguing for the existence of a very large animal, Architeuthis, in the North Atlantic. The animal had been given its scientific name years earlier by a Danish scientist, but there were still those who contested its existence.

Harvey understood the importance of having a genuine specimen. He had the 19-foot-long lump of flesh exhibited in the town’s museum. He coiled the tentacle like a snake and had a drawing made. He also had a photograph taken. He sent a written report across the sea to the British Annals and Magazine of Natural History. The journal published the package under the title “Gigantic Cuttlefishes in Newfoundland.”

The animal was, of course, not a cuttlefish (a small kind of cephalopod) but a huge squid. The misidentification is not surprising, given the mystery that then surrounded the species. Harvey’s submission ended a scientific controversy that had existed for centuries and grown increasingly personal and even bitter as the nineteenth century progressed. Seafarers had long claimed that a massive, vicious animal lived in the deep sea. They said that the animal sometimes attacked ships and could tear a man to pieces. Whalers claimed the monster was as large as—if not larger than—a whale. They believed these monsters attacked whales. They had seen six-foot scars, made by what they thought were huge claws, on the skin of the sperm whales they took out of the sea. When they opened the whales, they found what looked like prodigious parrot beaks in the whales’ stomachs. The whalers’ stories were part of an eons-old tradition regarding an animal called by various names—“Kraken,” “the Sea Monk,” “the Great Sea Serpent,” and even “the Great Calamary”—that lived in the sea. Odysseus’s six-headed Scylla may have been part of that tradition, according to author Richard Ellis.

Reports of the animal had been sporadic and confused. The tales told by the frightened people who saw the animal were so varied that it was difficult to tell whether they were seeing the same species all over the world, or a wide variety of animals with only a few characteristics in common. Classical Greeks told of a hydra, a nine-headed serpent. The New England Pilgrims said they saw in the 1630s a “coiled sea serpent” on the rocks on the Cape Ann shoreline. In 1734, the Bishop of Greenland insisted he had seen a “web-footed serpent” during an Atlantic crossing. In 1851, Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick described “the most wondrous phenomenon which the secret seas have hitherto revealed to mankind. A vast pulpy mass, furlongs in length and breadth, … curling and twisting like a nest of anacondas.”

Throughout the nineteenth century, as people increasingly plied the sea, reports of “a wonderful fish” in the globe’s oceans multiplied. Scientists remained skeptical. These confident—sometimes overconfident—men of the Victorian Age scoffed: How could the earth or the sea contain an animal so large that remained unknown to science? At that time, science theorized that no life could survive in the cold and lightless ocean depths, so the creature should have lived near the surface and been easily seen. No hard evidence existed to prove the sailors’ claims. With little more than fishermen’s tales, the scientists said, there was no reason to believe in the beast’s existence.

Sailors and fishermen took umbrage. They knew very well that life existed deep down in the ocean. They had firsthand knowledge: Harpooned sperm whales often dove thousands of feet below to escape their fate and whalers routinely paid out thousands of feet of line to keep the animals from escaping. They also knew that the stomachs of these whales contained all kinds of unusual species that were rarely seen at the sea’s surface. These strange beings had to live somewhere in the ocean.

Nevertheless, despite the specific knowledge provided by sailors and seafarers, science stuck to its dogma: Nothing could survive the water pressure deep below. No such thing as a giant squid could possibly exist.

In 1848 the matter came to a head. Peter McQuhae, captain of the British HMS Daedalus, reported seeing a 60-foot sea monster, nothing like a whale, floating on the water near the Cape of Good Hope. McQuhae wrote that he and his officers saw the thing at such a close range that, had it been a man, they would have seen his facial characteristics quite clearly. The animal moved at a speed of about 10 knots, the captain wrote.

Richard Owen, a paleontologist and a gifted scientific giant of his age who had coined the word “dinosaur,” ridiculed the captain. Owen, not well known for his pleasing personality, may have felt some righteousness regarding the naming of cephalopod species, as he was the first scientist to describe the nautilus, the cephalopod that lives inside the beautiful pearly shell. Many sea peoples knew about the shell, which could float for hundreds and even thousands of miles once the animal inside was dead, but until Owen came along, no European scientist knew the detailed natural history of the animal that lived inside.

Owen was unwilling to believe in the existence of a humongous animal so closely related to the tiny nautilus. He did not just publicly disparage McQuhae’s claim. He hacked away at the sea captain’s personal credibility, implying in print that McQuhae was either a liar or a fool. According to Owen, the captain had seen nothing other than a very large seal or sea elephant (what we would today call an elephant seal).

McQuhae resented the implied slander, which subtly suggested that he wasn’t equal to the task of ship’s captain. McQuhae insisted that he certainly knew the difference between an elephant seal and a 60-foot sea monster. The battle raged on. Neither side would let the matter drop. Seafarers, scientists, and the British upper class continued to write treatises on McQuhae’s sighting for decades after. As the years passed, more and more people came to accept that such an animal existed. “But science, incredulous, evidently will never be satisfied till it has a body to dissect,” Sir William Howard Russell wrote, taking McQuhae’s side in his 1860 book, My Diary in India.

Then came Theophilus Piccot’s severed tentacle. Measured at 19 feet and tangible beyond dispute, the putrefying prize ended the argument. Piccot’s animal came to be acknowledged as a squid—Architeuthis, the earth’s largest then-known invertebrate. The word comes from the Greek, “archi” meaning “chief,” and “teuthis” meaning “squid.”

Among those vindicated was Jules Verne, whose 1870 smash hit Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea tells of a gargantuan and malevolent monster that attacks a marvelous if seemingly fantastic electrically powered submarine (no such thing yet existed) and devours a crew member. Verne based his story on a similar giant squid sighting by a French sea captain, who had managed to bring home a tiny bit of flesh to prove his story. The French captain was also ridiculed by scientists, some of whom claimed the captain’s prized flesh was probably little more than a decaying bit of plant life.

But by the 1880s, after the publication in a respectable scientific publication of Theophilus Piccot’s excellent adventure, the controversy seemed settled. The existence of at least one species of giant squid seemed proven. In 1883, only a decade after Piccot’s encounter with a live specimen, the International Fisheries Exhibition in London exhibited a massive model giant squid. Sea Monsters Unmasked, a pamphlet distributed at the exhibition that year by marine biologist Sir Henry Lee, suggested that many of the sea monsters written about over the millennia were nothing more than run-of-the-mill giant squid.

The public thrilled to the frightening confirmation of the existence of so awful an animal. The Fisheries Exhibition giant squid model was suspended rather ominously above the heads of long-skirted Victorian ladies and high-hatted Victorian men. The model squid was a slightly bug-eyed squid, with its two feeding tentacles stretched well beyond its other appendages. Designed to create awe in the public’s mind, the model wasn’t entirely anatomically correct, but it was fairly well done for an animal whose existence had been, only a decade earlier, very much in doubt.

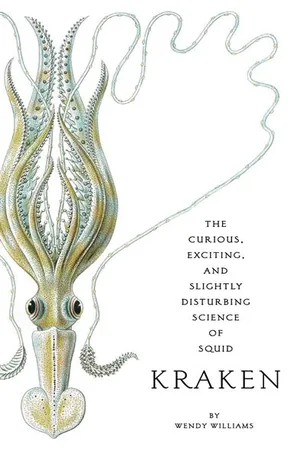

A giant squid at the International Fisheries Exhibition (1883)

Evolutionarily speaking, it took a long time for the giant squid to appear. Five hundred forty-two million years ago, about four billion years after earth came into being and perhaps three billion years or so after the simplest life-forms took shape, there occurred one of the most important events in the history of our solar system: the sudden radiation of life forms in earth’s oceans.

This milestone, called the Cambrian Explosion, was a bit miraculous, a bit bizarre; extraordinary, but perhaps at the same time, scientifically speaking, inevitable. Before this divide, life existed on earth, but, quite frankly, it didn’t amount to all that much, at least not to our modern eyes. There were no plants. For much of that time, there were no animals. From our point of view, it would have been a rather boring planet. But there was a lot going on behind the scenes. The stage was being set. Simple viruses and bacteria were probably around for quite a while, but evolution merely crept along. Then fungi and algae and simple single-celled animals proliferated.

Their presence freed up for the first time large amounts of oxygen in the atmosphere. Gradually, more complex animals evolved. But there was nothing of great size, nothing that would impress most of us today. Then, in a few tens of millions of years before the Cambrian, animals somewhat resembling a few of today’s animals finally evolved.

About 555 million years ago, or 20 million years before the Cambrian Explosion, tiny Kimberella appeared. In some ways, the fossils of these tiny animals looked like jellyfish, and scientists at first assumed that’s what they were, in part because mainstream science held that sophisticated life probably did not exist before the Cambrian. But as more examples turned up, closer inspection revealed several mollusklike features. The creature had a protective shell, a soft body, and probably a radula, a tonguelike structure common to most mollusks even today. Today, many scientists believe that Kimberella, only a few inches long but apparently plentiful in the earth’s shallow seas, may be the earliest known ancestor of today’s squid, including the giant squid.

A Kimberella

If it’s true that Kimberella was actually a mollusk, paleobiologists will have to rethink the earth’s evolutionary timeline. Scientists postulate the existence of a proto-animal called urbilateria from which much of the planet’s animal life has evolved. From this hypothetical “first animal” derived two superphyla or major divisions—the deuterostomes, from which we descend, and the protostomes, to which mollusks, including the cephalopods, belong.

Hypothetical family tree

Kimberella’s pre-Cambrian appearance means that the hypothetical urbilateria and its two superphyla must be far older than scientists once believed, perhaps having evolved well before 700 million years ago. And because humans and squid share so much basic biology, like the camera eye and the neuron, urbilateria may also have possessed the foundation for some of this basic biology. In other words, the evidence suggests an exciting idea: that very early life on our planet may have been much more sophisticated than we currently believe. The more we know about cephalopods, the more progress we will make in unraveling this mystery.

About 100,000 known species of mollusks live on our planet, although there may be another hundred thousand mollusk species not yet discovered and named. Mollusks live in every one of our ecosystems, except the desert, which is too dry for these moisture-loving animals. All mollusks are soft-bodied, like worms. But unlike worms, mollusks are not segmented.

Mollusks have a head, a main body, and a foot (even Kimberella appears to have been organized this way). They are often, but not always, protected by a covering shell. The mollusk’s body contains vital organs like the stomach and intestines. The head contains sensory organs like eyes and either a simple nerve center or a true brain. The mollusk’s foot is a tough muscle controlled by nerves connected to the animal’s head. It’s called a foot because the animal uses it as such, flexing its muscles to creep along the seafloor in search of food or to escape predators.

Mollusks also usually have a radula, a tonguelike, somewhat firm structure in the animal’s mouth. Covering the radula are numerous rasping, tough, tiny hooks that remind me of Velcro teeth. In some mollusks, these hooklike teeth scrape algae and other food off objects like rocks or off the seabed itself. In other species, the radula is part of the digestive system and abrades prey into small, consumable bits; it is sometimes so effective that the swallowed food resembles pabulum.

If Kimberella was truly the first mollusk, it was an astonishingly successful organism: Today, roughly a quarter of the sea’s animal species are probably mollusks. As befits one of the planet’s oldest phyla, modern mollusks vary widely. On the one hand, some are small enough to live between grains of beach sand and weigh less than an ounce. On the other hand, the giant squid and the colossal squid, weighing hundreds of pounds, are also mollusks. In addition, the mollusk group includes scallops, mussels, abalones, and snails.

During the Cambrian Explosion, most of the planet’s major animal group...