![]()

oko and Keisuke were hiding in an abandoned building. Like many Japanese children, they had been evacuated from war-torn Tokyo and brought to the countryside. They were hungry. But Yoko was less distressed about her empty stomach than about her usually upbeat younger brother’s listlessness.

“Let’s create a menu, OK?” she said. “Think of the dinner you want to eat.”

After some prodding, he offered, “I want ice cream.”

“But that’s a dessert,” she said. “We should start with soup, of course.”

Yoko goaded him some more, and together, lying on their backs and looking up at the ceiling, they created fantasy menus as though ideas alone could feed them. Through a crack in the roof, Yoko caught a glimpse of the blue sky, and at that moment she felt certain that everything would be all right.

It wouldn’t be the last time the sky would provide comfort and imagination would seem to have the power to save her life.

NORMALLY, YOKO ONO was not a child who seemed in need of saving. Her family was wealthy and powerful, and her lineage included scholars, warriors, and rulers. But she never would have been born if Eisuke Ono and Isoko Yasuda hadn’t done something unusual for Japanese people in the early 1930s: They married for love.

Yoko’s father, Eisuke, came from a long line of scholarly samurai warriors. He could even claim to be the descendant of a ninth-century emperor. Eisuke’s father was a Tokyo banker who, like Eisuke’s mother, valued education. Their son earned advanced degrees in economics and math at Tokyo University. Eisuke’s true passion, however, was music. He was moved by Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, and some of the other composers of Europe—not the Eastern musicians he had grown up listening to.

Eisuke embarked on a professional career as a pianist. He was a favorite performer at social events in Karuizawa, a village in the mountains a hundred miles north of Tokyo, where his family—well-off but certainly not rich—had a summer home. Given Eisuke’s good looks, smarts, and obvious talent, it was no wonder that young women considered him a catch.

Around Karuizawa, Isoko Yasuda was impossible to miss. She was exceptionally beautiful, fashionable, and wealthy. Her paternal grandfather, Zenjirō Yasuda, had been the founder of the prominent Yasuda Bank. Zenjirō was succeeded as head of the bank by Isoko’s father, Zenzaburo. Practically everybody in Japan had heard of the Yasudas. Isoko could have married just about anyone she wanted to.

After Isoko and Eisuke began a romance, Eisuke’s dream of furthering his musical career began to fall apart. Isoko had grown up like a princess, in an extravagant household with thirty-odd servants. She was chauffeured around in a private car and rewarded with diamonds just for getting good grades. Her parents didn’t approve of their daughter, whose assets far exceeded Eisuke’s, marrying a musician. It didn’t help that he, like a small minority of Japanese, was Christian. The Yasudas were Buddhist.

In Japan, as in the West at that time, a married man was seen as the provider for the household, and a musical career didn’t guarantee a good income. But in the end, it wasn’t Isoko’s parents who convinced Eisuke to give up his musical ambitions. After his father died, Eisuke learned from his will that he wanted his son to stop playing the piano and follow in his footsteps by becoming a banker. Eisuke agreed—reluctantly—to give up music to honor his dead father’s wishes and to please the parents of the woman he loved.

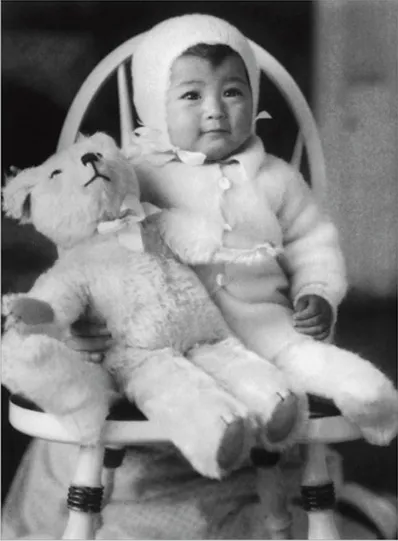

After Eisuke and Isoko wed, he moved into the dauntingly large Yasuda compound, where Isoko had been living, in the ancient city of Kamakura, which overlooked Tokyo. It was in those palatial surroundings that Yoko came into the world one snowy night, on February 18, 1933. But Eisuke wasn’t there for Yoko’s birth. Two weeks earlier, he had been transferred from a bank in Tokyo to one in San Francisco. In Yoko’s first memory of her father, he is a mysterious stranger looking out at her from a photograph. “My mother would show me his picture before bedtime and tell me, ‘Say good night to Father.’”

Yoko was born into a wealthy family, but she didn’t have everything: She didn’t meet her father until she was two and a half years old.

Yoko didn’t actually meet Eisuke until she was two and a half years old, when she and her mother traveled by ship to California to be with him. “My father looked like a tall American Indian chief,” she said. “He stood straight; he was elegant and proud.” But she didn’t sense that he was happy to meet her.

It was in California that Yoko gave her mother a shock that would steer the way Isoko raised her daughter. While the Onos were in the dining room of a hotel near Yosemite National Park, where the family was taking in the sights, Yoko stood before some elderly women and, out of the blue, started singing Japanese children’s songs.

Isoko was horrified by what she heard coming from her daughter’s mouth. She considered these songs the music of commoners and therefore a sign of poor breeding. She knew that Yoko could have learned the songs only from her nannies back in Japan. Isoko vowed to send Yoko, once she was old enough, to Tokyo’s best private schools, where the little girl would learn what her mother viewed as proper behavior.

In the spring of 1937, the family, which now included baby boy Keisuke, returned to Tokyo. Isoko and Eisuke had sensed that it was time. Japan was openly pursuing its ambition to become a world superpower by sending troops to China, a friend to the United States. This intrusion created anti-Japanese sentiment in America. Yoko’s parents could feel it.

This picture was taken in San Francisco circa 1935, not long after Yoko met her father, Eisuke, for the first time. Her mother, Isoko, was a very protective parent. Yoko recalled, “My attendants always carried absorbent cotton dipped in alcohol on an occasion like a family trip. They disinfected every place I was likely to touch on a train. That was because of my mother’s partiality for cleanliness. Thus, I became sensitive to cleanliness too.”

The family was now living in a Western-style mansion in Azabu, one of Tokyo’s affluent residential districts. Isoko followed through on her pledge to give her daughter only the best by sending her to Jiyu Gakuen, a celebrated Tokyo school for girls that Isoko herself had attended as a child. Known for producing some respected Japanese musicians, the school taught even very young children piano, pitch, harmony, and composition. Yoko began at Jiyu Gakuen when she was only four years old—her age when she gave her first public concert, on piano. She had never been so nervous in her life. Performing didn’t get easier right away. “I remember running offstage and throwing up after one concert,” she recalled.

She liked learning about and writing music, though. One of the things she learned at Jiyu Gakuen was to listen to sounds in her environment. For homework she was asked to translate everyday noises, like street traffic or a bird’s song, into musical notes.

But Isoko didn’t think that Jiyu Gakuen was quite good enough for her daughter. The following year she sent Yoko to an even more prestigious school called Gakushūin. The school was located near Tokyo’s Imperial Palace, where Japan’s imperial family lived, and it accepted students only if they were related to the imperial family or to members of the House of Peers, part of Japan’s parliament. Yoko’s acceptance was guaranteed: Her grandfather Zenzaburo had been inducted into the House of Peers in 1915, long before she was born. She took her place among the other privileged children of royalty and government officials.

At Gakushūin, Yoko continued to learn about music. She wrote songs and created drawings to go with her melodies. She also wrote haiku, a form of Japanese poetry made up of three nonrhyming lines that together usually contain exactly seventeen syllables. “People used to say, ‘When Yoko takes steps, a poem comes out of her mouth as she stops,’” she said later.

EISUKE MARVELED AT Yoko’s musical ability. He was happy to provide her with an extensive musical education that included private lessons. But Eisuke was inaccessible as a father, forever preoccupied with work even when he wasn’t away on business (as he frequently was). “My father had a huge desk in front of him that separated us permanently,” Yoko later wrote.

Her mother was a similarly elusive presence. Isoko was known for giving lavish Hollywood-style parties for Tokyo’s glamorous social elite. “It was like having a film star in the house,” Yoko said of her mother. When Isoko entertained, Yoko often watched from afar, usually attended by one of her nannies. She was enchanted by the scene—it was like some fairy-tale ball—but she knew that Isoko didn’t want her in the picture. “My mother had her own life. She was beautiful and looked very young. She used to say, ‘You should be happy that your mother looks so young.’ But I wanted a mother who made lunch … and didn’t wear cosmetics.”

And she wanted one who didn’t criticize her daughter’s looks. Isoko would tell Yoko that she was “handsome” but “not pretty; pretty girls don’t have those big [cheek]bones.” For Yoko, this was particularly hurtful coming from someone who obviously put much stock in appearances.

Isoko excelled in many of the arts, especially painting and drawing, and she took the time to share her skills and techniques with Yoko. She once warned her daughter against marriage and motherhood, claiming that they had prevented her from having a career as a painter. “She was always … intimidating because she was such a good painter,” Yoko said. “When I was a little girl, and I had to do homework for a painting class, she’d say, ‘No, no. Just wait, wait. Do it this way.’ And one day, I had to take this piece of work to school that was [practically] done by her. I was feeling so embarrassed, but there was no choice but to take that painting to school. Everyone was saying, ‘It’s so good. I can’t believe it’s so good.’”

Like Eisuke, Isoko acknowledged Yoko’s artistic talents, and like him, she raised their daughter from an emotional distance. She told her servants to let Yoko get up all by herself when she fell down—in hopes that the experience would make the little girl stronger and more independent. “I still remember … several women in kimono staring at me without offering a hand while I was trying to get up from the ground,” Yoko later wrote.

At Gakushūin, Yoko stood apart from other kids her age. Petite in comparison, she also appeared more mature and worldly than her peers. Most Japanese children were raised to act subservient out of respect for their elders at all times, even bowing before their teachers. Yoko was different. She was less afraid than her classmates to ask questions, sometimes even challenging her elders.

Her parents may not have anticipated this side effect of Yoko having lived in the United States, where adults often encouraged children to freely offer their opinions. Still, Isoko and Eisuke were determined that their daughter grasp the English language and be familiar with Western culture. This was important to many Eastern families, who saw knowledge of Western ways as a ticket to success. But that kind of success wasn’t on Yoko’s mind. “I was terribly lonely,” she said. “At school … I didn’t have any friends.”

Yoko wears a medal she won in kindergarten in 1937.

When she wasn’t in school, Yoko was constantly in the company of servants and teachers: “There were several maids and private tutors beside me. I had one private tutor who read me the Bible and another foreign tutor who gave me piano lessons, and my attendant taught me Buddhism.” At times she turned to her caretakers for friendship, comfort, even love—a risky proposition, considering there was no way of knowing how long they would be working for her parents. They were often let go quickly because Isoko had such high standards. When the servants left, Yoko feared that it was her fault.

Her intellectual needs were being met by instructors, her day-to-day needs by household staff. Yet Yoko still felt abandoned. She longed for her parents to spend more time with her. She later wrote of eating her meals alone: “I was told the meal was ready and went into the dining room, where there was a long table for me to eat at. My private tutor watched me silently, sitting on the chair beside me.” Isoko forbade her from visiting the children of the servants, but at times, because she was desperate for someone to play with, Yoko would approach the daughter of one of her caretakers. When the surprised little girl realized that Yoko wanted to actually play with her, her reply was a submissive “I would do whatever you wish to, miss” or “What would you like to do, miss?”

EISUKE WAS WORKING for a bank in New York in 1940—a time of escalating tension between Japan and the United States. After Japan began aggressively mining China’s natural resources in its attempt to become a world power, the United States had come to China’s aid. Now many Americans were wondering if Japan would retaliate against the United States.

Meanwhile, in yet another part of the world, Germany’s chancellor, Adolf Hitler, was heading a murderous campaign to expand the German empire. His Nazi Party, which believed in the superiority of the German race, was singling out for death anyone who wasn’t part of the white, Christian, able-bodied mainstream, including Gypsies, gays, the disabled, and, especially, Jews. The United Kingdom and France had already declared war on Germany. But Japan and Italy joined forces with Germany, and the three became known as the Axis powers. They pledged to support one another against their adversaries.

Because of this unrest, Isoko feared that the U.S. government would soon impose travel restrictions, which would mean that it might be years before she could see her husband again. So she bravely brought Yoko and her brother, Keisuke, by ship to California, and from there they took a train across America to New York. The Ono family set up house on Long Island, where Yoko went to public school and became fluent in English.

But a year later, in the spring of 1941, just as eight-year-old Yoko was flourishing academically and starting to make friends, Isoko decided that it was time for her and her children to sail back to Tokyo: She and Eisuke were certain that a war between Japan and the United States was imminent. Yoko, too, knew that something was brewing. Children in her own neighborhood were friendly to her, but if she went just a couple of blocks away, kids who lived there would throw stones at her simply because she was Japanese. She couldn’t even escape from her race at the movies: “I remember being in film theaters where the baddies were always Asian. When the lights went up, I thought, am I [a baddie too]?”

Eisuke, who sailed home to Japan several weeks after his family did, didn’t stay put in Tokyo for long: He was soon sent to manage a branch of his bank in Japanese-occupied Hanoi, the capital of French Indochina (which later became Vietnam). Yoko disliked her father’s absences, but she was used to them.

Yoko on an ocean liner to meet her father for the first time.

The United States was trying hard to stay out of the turmoil going on in the world. Aside from offering aid to China and refusing to give oil and other necessities to Japan, the country remained politically neutral. But on December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, a U.S. Navy base on the Hawaiian island of Oahu. Around twenty-five hundred servicemen and civilians were killed. The United States declared war the following day, joining up with the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and the other Allied nations working together to defeat the Axis powers. Young as she was, Yoko picked up on the fact that her parents didn’t believe in war and thought that what Japan had done was unconscionable.

Initially, the Onos’ wealt...