![]()

Chapter One

The Mannahatta Project

As the moon rose higher the inessential houses began to melt away until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes—a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees … had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.

— F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby 1925

On a hot, fair day, the twelfth of September, 1609, Henry Hudson and a small crew of Dutch and English sailors rode the flood tide up a great estuarine river, past a long, wooded island at latitude 40°48’ north, on the edge of the North American continent. Locally the island was called Mannahatta, or “Island of Many Hills.” One day the island would become as densely filled with people and avenues as it once was with trees and streams, but not that afternoon. That afternoon the island still hummed with green wonders. New York City, through an accident, was about to be born.

Hudson, an English captain in Dutch employ, wasn’t looking to found a city; he was seeking a route to China. Instead of Oriental riches, what he found was Mannahatta’s natural wealth—the old-growth forests, stately wetlands, glittering streams, teeming waters, rolling hills, abundant wildlife, and mysterious people, as foreign to him as he was to them. The landscape that Hudson discovered for Europe that day was prodigious in its abundance, resplendent in its diversity, a place richer than many people today imagine could exist anywhere. If Mannahatta existed today as it did then, it would be a national park—it would be the crowning glory of American national parks.

Mannahatta had more ecological communities per acre than Yellowstone, more native plant species per acre than Yosemite, and more birds than the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Mannahatta housed wolves, black bears, mountain lions, beavers, mink, and river otters; whales, porpoises, seals, and the occasional sea turtle visited its harbor. Millions of birds of more than a hundred and fifty different species flew over the island annually on transcontinental migratory pathways; millions of fish—shad, herring, trout, sturgeon, and eel—swam past the island up the Hudson River and in its streams during annual rites of spring. Sphagnum moss from the North and magnolia from the South met in New York City, in forests with over seventy kinds of trees, and wetlands with over two hundred kinds of plants. Thirty varieties of orchids once grew on Mannahatta. Oysters, clams, and mussels in the billions filtered the local water; the river and the sea exchanged their tonics in tidal runs and freshets fueled by a generous climate; and the entire scheme was powered by the moon and the sun, in ecosystems that reused and retained water, soil, and energy, in cycles established over millions of years.

Living in this land were the Lenape—the “Ancient Ones”—of northeast Algonquin culture, a people for whom the local landscape had provided all that they and their ancestors required for more than four hundred generations before Hudson arrived. On Mannahatta these people lived a mobile and productive life, moving to hunt and fish and plant depending on the season; they had settlements in today’s Chinatown, Upper East Side, and Inwood, and fishing camps along the cliffs of Washington Heights and the bays of the East River. They shaped the landscape with fire; grew mixed fields of corn, beans, and squash; gathered abundant wild foods from the productive waters and abundant woods; and conceived their relationship to the environment and each other in ways that emphasized respect, community, and balance. They lived entirely within their local means, gathering everything they needed from the immediate environment, participants in and benefactors of the rhythms of the nature that obviously connected them to their island home.

Manhattan is the archetype of the twenty-first-century city, providing food, water, shelter, and meaning to millions of people, on a planet of billions. The human population is increasingly urbanized; by 2050, 70 percent of the world’s population may live in cities.

Mannahatta is an archetype of nature—nature in all its diversity, abundance, and robust interconnections. In 1609 it also supported a human population three hundred to twelve hundred strong.

Many things have changed over the last four hundred years. Extraordinary cultural diversity has replaced extraordinary biodiversity on the island; today people from nearly every nation on earth can be found living in New York City. Abundance is now measured in economic currencies, not ecological ones, and our economic wealth is enormous —New York is one of the richest societies the world has ever known, and is growing richer each year. Millions of people fly in from all over the world to a narrow, twelve-block-wide island to gather in buildings a thousand feet high to see what’s new and what’s next. Thousands of tons of materials follow them into the city—foodstuffs from six continents and four oceans; concrete and steel and clothing from the other side of the globe; power from coal, oil, and atomic fission—all the resources necessary for the modern megacity, delivered as the natural systems once delivered, through elaborate networks, though now the networks are composed of people, products, money, and markets, as opposed to forests, streams, sunshine, and grass.

It is a conceit of New York City—the concrete city, the steel metropolis, Batman’s Gotham—to think it is a place outside of nature, a place where humanity has completely triumphed over the forces of the natural world, where a person can do and be anything without limit or consequence. Yet this conceit is not unique to the city; it is shared by a globalized twenty-first-century human culture, which posits that through technology and economic development we can escape the shackles that bind us to our earthly selves, including our dependence on the earth’s bounty and the confines of our native place. As such the story of Mannahatta’s transformation to Manhattan isn’t localized to one island; it is a coming-of-age story that literally embraces the entire world and is relevant to all of the 6.7 billion human beings who share it.

To many outsiders, Manhattan Island is a monument to self-grandeur and a potent symbol of the inevitable—but yet to be realized—collapse of our hubris. But inside of New York another way of thinking is emerging, a new set of ideas and beliefs that do not depend on disaster to correct our course and instead imagines a future where humanity embraces, rather than disdains, our connection to the natural world. Many New Yorkers celebrate the nature of their city and seek to understand the city’s place in nature. They see their city as an ecosystem and recognize that, like any good ecosystem, the city has cycles, flows, interconnections, and mechanisms for self-correction. New Yorkers love their place with a ferocity that the Lenape would have recognized; active observers of and participants in their neighborhoods, where every change is a source of discussion and debate. We know, when we stop to think of it, that no place can exist outside of nature. As was true for the original Manahate people, our food needs to come from somewhere; our water, our material life, our sense of meaning are not disconnected from the world, but exactly and specifically part of it.

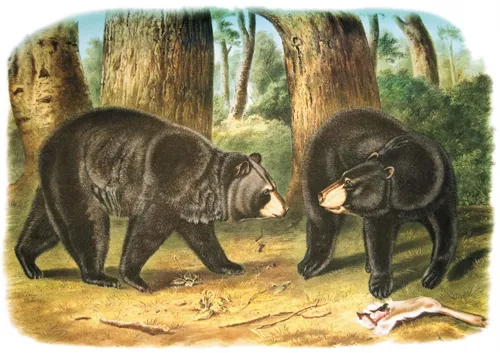

The black bear was abundant in the forests and meadows of Mannahatta in 1609. One was shot in the vicinity of Maiden Lane, in Lower Manhattan, in 1630. This painting by John James Audubon dates from the nineteenth century, but could easily have been from Mannahatta two hundred years before.

To ecologists, a landscape is the mosaic of different types of ecosystems that makes a particular place unique. The combination of different ecosystem types makes habitat for species, like these white-footed mice, or, in an urban context, for people.

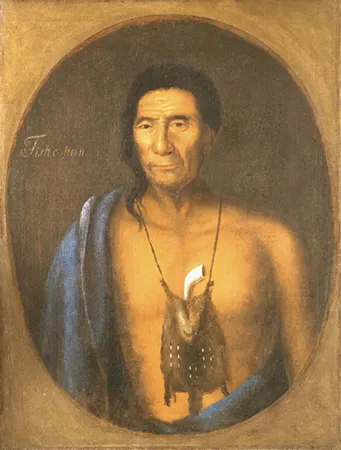

The New World that Henry Hudson explored had long been inhabited by Native Americans; the Lenape and their ancestors had inhabited Mannahatta and its surrounding areas for perhaps ten thousand years prior to Hudson’s arrival. This portrait by Gustavus Hesselius, from the 1730s, depicts the Lenape sachem Tischohan, from Pennsylvania. No images of the Lenape from Mannahatta exist today.

Moreover, we are coming to realize that cities are ecological places to live. The average New Yorker emits 7.1 tons of CO2 into the atmosphere each year; the average American, 24.5 tons. A third of the public transit trips made in America each year are made in New York. New York is a leader in urban planning and green buildings. The city has seen some of its wildlife return, from the expanding fish runs to the restocked oyster beds to bird populations that give Central Park some of the best, most concentrated bird-watching in the country. New Yorkers recycle and compost; we use energy-efficient bulbs; we meter our water usage; we have a system of bike lanes and kayaking spots. I can see wild turkeys not five minutes from my front door, in a park with a wildlife sanctuary. This isn’t to say New York has done everything necessary to be sustainable—we are still cursed with the automobile and an enormous appetite for resources—but we’re moving in the right direction.

All of this was news to me when I moved to New York ten years ago, delivered from a comfortable life in suburban northern California, drawn to the city, like many newcomers, by a job, a new way to make a living. I boxed up my bicycle; bought a soot-colored trench coat and a black hat; packed my volumes of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and John Muir; said good-bye to the local food co-op; and clambered into my beat-up blue ’77 Volvo station wagon to drive east. My friends thought I was crazy. Like Hudson, I came to New York looking for something, but once here found something else—something I wasn’t expecting at all.

Coming to New York

In 1998, as a young, newly minted PhD scientist from the University of California, Davis, I arrived to take up employment with the Wildlife Conservation Society, based out of Bronx Zoo, in New York City. Most non-conservationists don’t know what the Wildlife Conservation Society is, at least by that name, but it is a venerable institution, founded in 1895 as the New York Zoological Society, and one of the first wildlife conservation organizations in the world. I soon learned that telling people, even people I met in New York, that I worked for the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) was not a successful strategy. Usually I received a bemused but blank look—did I save baby seals from the slaughter? Did I harass whalers from a rubber raft? Was I a member of yet another conservation group whose name starts with a W? (Even my mom sometimes accidentally introduces me as working for the “World Conservation Society.” That group, sadly, doesn’t exist.)

I thought a better gambit was to tell new acquaintances that I worked at the Bronx Zoo, which everyone had heard of—but that introduction led to new misunderstandings. No, I didn’t keep the elephants or get to play with the gorillas. I rarely got to go behind the exhibits. Rather, I mainly worked on the computer and helped incredibly dedicated and intelligent people do their utmost to save wild animals in large, natural landscapes in Africa, Asia, and the Americas—not through stunts, but through the hard work of science, consensus, and long-term engagement. It sounds like bragging, but it’s true: you can’t believe these people or the places they work. In the heart of a cultural institution that New Yorkers loved for sharing time with their families, there was an extended family of people trying to save the world. The WCS, though nearly unknown in New York, was known to people all over the world as one of the most practical and efficient scientific conservation organizations. I had taken a job where on a rotating basis I worked to help save tigers, the oceans, and the Eastern Steppe of Mongolia, among other things. Not bad.

The price was abandoning my easygoing existence in the Sacramento Valley for the big city, which even today I would not describe as easygoing, just a bit on the brash side. I struggled to find my place in New York and, as a coping mechanism, started visiting the city’s wilder places and reading about its history. I found winter bewildering (is that really ice floating in the harbor?), spring late coming (how long can a forest exist as just sticks and no leaves?), and summer discomfiting (I thought this was the temperate zone), but I liked the fall, with clear, blue skies, warm weather, and sparkling waters. I learned New York City was built on an archipelago in an estuary. New Amsterdam, as it was first known, was originally settled by the Dutch—a remarkably diverse and tolerant seventeenth-century people, if a bit moneygrubbing—and, later, New York played a major role in the American Revolution. Battles were fought in 1776 along the same ground as the bike path where I rode to work; Revolutionary snipers once hid in a hundred-plus-foot white pine that stood beside the Bronx River. Teddy Roosevelt, who as president had protected so many of the landscapes out West that I loved, had himself fallen in love with nature sailing and hiking on Long Island (and helped found the WCS as a result). Strangely, though, for all the city’s history and nature, most New Yorkers didn’t seem to know about it, either not remembering their grade-school lessons or, like me, arriving from new places having never learned them.

The Hudson River estuary shaped the ...