![]()

A

I grew up in a small town in northern Minnesota. Hockey was the big game, and golf was something we played only in the summer. There were no such things as junior programs, and I never had a lesson.

But somehow, my high school golf team was good enough to win the state championship. What I remember most about that event was that it was the first time I had played a course with bunkers—I had never hit a sand shot before that week. I played all the rounds trying to avoid those large holes in the earth.

By that time, I had fallen in love with golf and decided that I wanted to make a living by playing the game. But given where I was from and my lack of experience in major junior events, the best I could do was a scholarship to Bemidji State University, a Division II program near my hometown.

Fired by the ambition to play Division I golf, I made a bold decision during my freshman year. The team had driven down to Corpus Christi, Texas, for a tournament, and on the way back, I asked the golf coach to drop me off in the parking lot of a Motel 6 in Denton, the home of North Texas State University (now known as the University of North Texas).

The next morning, I walked to the campus and inquired about getting on the golf team. When I look back on what I did, I am amazed that an eighteen-year-old just decided to leave a school where he had a scholarship and move across the country to attend a university where there wasn’t a guarantee that he would even make the team.

But I had done a little research, and North Texas was where I wanted to be. The university had won four consecutive national championships, from 1949 to 1952. The star of that team was Don January, who later went on to win the 1967 PGA Championship, and the coach was Fred Cobb. It was said that University of Houston golf coach Dave Williams, the most successful golf coach in NCAA history, modeled his program after the way Cobb structured his team.

After talking to a few people, I realized that I would have to sit out a year. I couldn’t afford the out-of-state tuition, so I decided to work for a year to gain Texas residency. I got a job as a cart boy at the Trophy Club Country Club in Roanoke.

The Trophy Club was the only course ever designed by Ben Hogan, and he used to practice there from time to time. It was just one mile down the road from Byron Nelson’s ranch. For a kid from the Iron Range of Minnesota, this was golf heaven.

Besides earning some money and being able to practice, I was able to spy on the North Texas golf team, which played qualifying rounds there to decide which players would get to play in the next tournament. So I had an idea of how much I needed to improve to make that team.

I decided that what I really needed was to be a better putter. The Trophy Club’s assistant pro, who had hired me, told me to go see Harvey Penick in Austin. I had never heard of him, but I called Austin Country Club right away and scheduled a lesson.

When the day came to make the four-hour drive to Austin, I couldn’t have been more excited. I had never taken a lesson in my life, so I had no idea how much it cost or what the protocol was. I brought cash, my checkbook, and my mother’s credit card.

I was a little early for the lesson, so I started stroking some putts on the practice green. As I waited, my nervousness grew because it became apparent to me that Harvey was a big deal, and I didn’t want to do anything foolish in front of him. Harvey came out right on time and introduced himself. He immediately put me at ease, asking me questions about where I was from, how long I had been playing, my goals.

He then noticed my putter, a Wilson 8802, and asked how I had gotten to using it. I answered that my idol was Ben Crenshaw, not knowing at the time that Harvey had been Ben’s longtime teacher. I told him that I wanted to copy both his equipment and his stroke, which meant that I stood upright with my arms hanging down.

After I answered, Harvey asked me whether I knew the man behind me. I turned around and there was Crenshaw himself, waiting to talk to his teacher!

Crenshaw was standing off to the edge of the green because he was wearing cowboy boots. He introduced himself as if he were just any other member at the club welcoming a guest, and we got to talking about putting. Crenshaw asked to see my putter and set several balls on the fringe, about ten feet from the nearest hole.

He stroked the first putt with the smoothest, purest stroke I had ever seen. The putt had a little break and it was tracking directly at the hole, only to hit the lip and roll out. He then hit three more putts, each one in the dead center of the hole.

“This putter is a little more upright than mine,” Crenshaw said. “It has a good feel, though.”

I was beaming, and I’m sure my smile could be seen back in Minnesota.

Ben gave the putter back to me and returned to the clubhouse, leaving me to my lesson. I remember Harvey telling me that although Crenshaw’s method may have been popular at the time, there were other great putters and other ways of putting.

He then asked me how I had putted when I was younger.

“I bent way over and used my hands for feel,” I replied.

“Did you putt better then than you do now?”

“Yes,” I said reluctantly.

Harvey was trying to tell me that my natural technique was better than copying somebody else’s. Crenshaw’s style worked for him because that was his own technique, one developed over time. He hadn’t copied the methods used by Jack Nicklaus or Arnold Palmer.

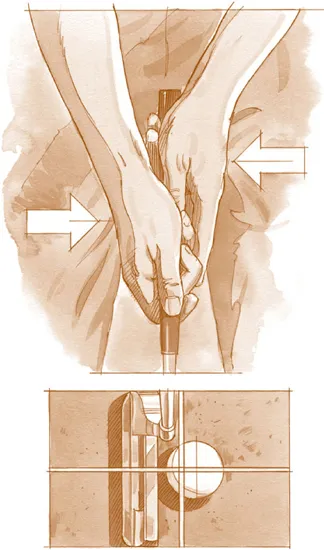

Harvey wanted me to develop my natural style, but he had three fundamentals that he didn’t want me to skip: put my thumbs on top of the grip, keep my eyes over the ball, and try to hit the ball in the middle of the putter face.

Of the three, he was most adamant about the grip, because the hands are the only part of the body in contact with the club and therefore have the most control over what the club does during the shot.

My eyes were in the correct position and I was making solid contact, but my thumbs weren’t on top of the club, so Harvey had me adjust my grip. Of course, I then started putting a lot better and began to regain confidence in my game. Over the next seventeen years, Harvey would continue to remind me now and again to keep my thumbs on top.

When I returned to Denton, everybody wanted to know what Harvey had told me. When I explained that he had fixed my grip, they all seemed disappointed because the advice was so simple. Like nearly everybody who had gone to see Harvey, they were probably thinking that he would have some more complicated knowledge to impart.

After the lesson, which lasted about an hour, Harvey invited me to go to the range and practice. Excited about what had just happened, I wound up hitting three bags of balls. If I’d had any doubts about leaving Minnesota to pursue my dreams, those moments on the range, awash in memories of the previous hour, obliterated them. Not only had I received my first lesson from one of the best teachers ever, I had met my idol!

After my practice session, I headed to the pro shop to settle up with Harvey. Crenshaw was talking to a group of members outside the entrance. I was too timid to walk up to the group, but Ben saw me and left his conversation to say good-bye to me. He even remembered my name and wished me luck in my quest to make the team at North Texas State. He also told me to listen to what Harvey said.

Nothing could bring me down from that high. As I entered the pro shop, however, I was a bit apprehensive about how much my amazing day was going to cost. Clutching all my various methods of payment, I sought out Harvey. When I asked how much I owed him, Harvey told me three dollars.

I was sure I had misheard, so I asked again.

“Three dollars for the three bags you hit,” he said. “And be sure to come back next month. We have a couple of things to work on.”

Needless to say, Harvey made a tremendous impression on me that day. He knew I didn’t have much money, and he went out of his way to help a young hillbilly getting his start in the golf world. I appreciated what he had done, and I couldn’t wait to come back in a few weeks.

Of all the lessons I learned that day, the biggest had nothing to do with golf. It was trust. At the next lesson, Harvey could have told me to putt while standing on my head, and I would have done it. I gave myself completely to him, and he came to know my game as well as I did—probably better. I always played a stronger game after seeing him, and I learned something about golf and life every time I talked to him.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, that day was the start of our lasting relationship, first as teacher and pupil then as mentor and apprentice, which lasted until he passed away in 1995.

In the following chapters, I will outline the most important lessons I have learned from him, and from various other people in golf. But I wouldn’t have learned any of them without the lesson of trust that I received during my first meeting with Harvey more than twenty years ago.

MARK’S LESSONS

It’s a natural tendency to want to emulate your favorite player. But what Harvey wanted to instill in me from our first lesson was the importance of playing with your own style, one that comes easily to you. Because it is natural, you can trust it, instead of having to think all the time about whether you are in the right position. That’s no way to play golf.

At our first lesson, Harvey made me realize that when I was trying to putt like Ben Crenshaw, I was thinking about whether I was standing in the correct posture and how far I should take back the putter, instead of thinking about pace and line.

With my natural, bent-over setup, I didn’t have to think about mechanics. Instead, I trusted my stroke, which allowed me to focus on making the putt. Trust is a big part of playing golf, and you have to find a way to incorporate it into your game.

HIGH HANDICAPPER

Having my thumbs on top of the grip while putting ensures that my hands face each other in a neutral position. In other words, it keeps the putter face square.

If your face isn’t square, it really doesn’t matter what else you do during the putting stroke, because your putts will never go where you want them to roll.

Harvey had two other must-follow fundamentals. Fixing your eyes over the ball ensures that the putter follows a straight path through impact. If the eyes are inside the ball (closer to your feet), the tendency is for the path to be from inside the target line, causing putts to roll right. If the eyes are outside the ball, the putter will approach the ball from outside the target line, causing pulled putts.

Hitting the ball in the middle of the putter face, which is where the sweet spot is located, ensures that the ball reaches the hole. Contact toward the heel or toe will come up well short of the hole.

MID HANDICAPPER

There is a lot to consider on every putt: Is my putter face square? Are my eyes over the ball? Is my ball position correct? How much break is there? Is the putt downhill? How hard should I hit it? Is this putt two balls outside left or just one?

There are a lot of opportunities for doubt to creep into your mind. And doubt is the worst thing you can have when you’re over a putt.

If you trust your stroke, all you need to do is determine the line and the speed. Then, you must commit to that putt completely, trusting that it will get the ball to the hole.

Even if your determination of the break is off-line by a little bit, you’re much better off trusting that line and your stroke than reading the break perfectly and second-guessing everything afterward. A trusting stroke is a confident stroke, and you’ll make many more putts if you putt with confidence.

LOW HANDICAPPER

Many low handicappers get caught up in how their swings look. Is my elbow in the correct position? Is my finish too high? Golfers often compare their actions with those of tour players.

Harvey believed that every player had a swing that worked for him or her, and he didn’t want his students copying others. As a result, he never let his two star pupils, Ben Crenshaw and Tom Kite, watch each other’s lessons. He didn’t want either of them picking up something that was only meant for the other.

It doesn’t matter what your swing looks like. All that matters is getting the ball in the hole. If beauty were important, a lot of great players would never have made it to the PGA Tour. Lee Trevino, Ray Floyd, Fred Couples, and Jim Furyk have swings that are far from textbook-perfect, but they have made their quirks work for them.

In...