- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

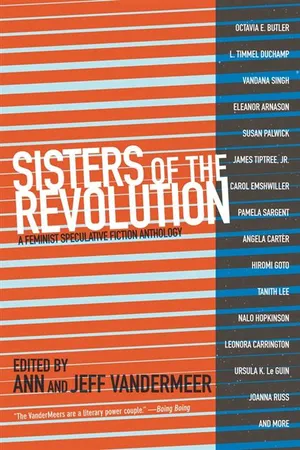

Sisters of the Revolution gathers a highly curated selection of feminist speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, horror and more) chosen by one of the most respected editorial teams in speculative literature today, the award-winning Ann and Jeff VanderMeer. Including stories from the 1970s to the present day, the collection seeks to expand the conversation about feminism while engaging the reader in a wealth of imaginative ideas. Sisters of the Revolution seeks to expand the ideas of both contemporary fiction and feminism to new fronts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sisters Of The Revolution by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Science Fiction. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Evening and the Morning and the Night

Octavia E. Butler was an American writer. As a multiple recipient of both the Hugo and Nebula awards, Butler was one of the best-known women in the field and has often been credited with inspiring many other writers both in and out of genre fiction. In 1995, she became the first science fiction writer to receive the MacArthur Fellowship. At the time, Butler was also one of the only African-American women in the science fiction field. In 2010, she was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame. Butler’s novels include Kindred (1979) and Parable of the Sower (1993). In “The Evening and the Morning and the Night” Butler creates a fictional disease and uses this story to explore how society deals with issues of illness and stigma. It was first published in OMNI magazine in 1987.

When I was fifteen and trying to show my independence by getting careless with my diet, my parents took me to a Duryea-Gode disease ward. They wanted me to see, they said, where I was headed if I wasn’t careful. In fact, it was where I was headed no matter what. It was only a matter of when: now or later. My parents were putting in their vote for later.

I won’t describe the ward. It’s enough to say that when they brought me home, I cut my wrists. I did a thorough job of it, old Roman style in a bathtub of warm water. Almost made it. My father dislocated his shoulder breaking down the bathroom door. He and I never forgave each other for that day.

The disease got him almost three years later—just before I went off to college. It was sudden. It doesn’t happen that way often. Most people notice themselves beginning to drift—or their relatives notice—and they make arrangements with their chosen institution. People who are noticed and who resist going in can be locked up for a week’s observation. I don’t doubt that that observation period breaks up a few families. Sending someone away for what turns out to be a false alarm … Well, it isn’t the sort of thing the victim is likely to forgive or forget. On the other hand, not sending someone away in time—missing the signs or having a person go off suddenly without signs—is inevitably dangerous for the victim. I’ve never heard of it going as badly, though, as it did in my family. People normally injure only themselves when their time comes—unless someone is stupid enough to try to handle them without the necessary drugs or restraints.

My father had killed my mother, then killed himself. I wasn’t home when it happened. I had stayed at school later than usual, rehearsing graduation exercises. By the time I got home, there were cops everywhere. There was an ambulance, and two attendants were wheeling someone out on a stretcher—someone covered. More than covered. Almost … bagged.

The cops wouldn’t let me in. I didn’t find out until later exactly what had happened. I wish I’d never found out. Dad had killed Mom, then skinned her completely. At least that’s how I hope it happened. I mean I hope he killed her first. He broke some of her ribs, damaged her heart. Digging.

Then he began tearing at himself, through skin and bone, digging. He had managed to reach his own heart before he died. It was an especially bad example of the kind of thing that makes people afraid of us. It gets some of us into trouble for picking at a pimple or even for daydreaming. It has inspired restrictive laws, created problems with jobs, housing, schools … The Duryea-Gode Disease Foundation has spent millions telling the world that people like my father don’t exist.

A long time later, when I had gotten myself together as best I could, I went to college—to the University of Southern California—on a Dilg scholarship. Dilg is the retreat you try to send your out-of-control DGD relatives to. It’s run by controlled DGDs like me, like my parents while they lived. God knows how any controlled DGD stands it. Anyway, the place has a waiting list miles long. My parents put me on it after my suicide attempt, but chances were, I’d be dead by the time my name came up.

I can’t say why I went to college—except that I had been going to school all my life and didn’t know what else to do. I didn’t go with any particular hope. Hell, I knew what I was in for eventually. I was just marking time. Whatever I did was just marking time. If people were willing to pay me to go to school and mark time, why not do it?

The weird part was, I worked hard, got top grades. If you work hard enough at something that doesn’t matter, you can forget for a while about the things that do.

Sometimes I thought about trying suicide again. How was it I’d had the courage when I was fifteen but didn’t have it now? Two DGD parents both religious, both as opposed to abortion as they were to suicide. So they had trusted God and the promises of modern medicine and had a child. But how could I look at what had happened to them and trust anything?

I majored in biology. Non-DGDs say something about our disease makes us good at the sciences—genetics, molecular biology, biochemistry … That something was terror. Terror and a kind of driving hopelessness. Some of us went bad and became destructive before we had to—yes, we did produce more than our share of criminals. And some of us went good—spectacularly—and made scientific and medical history. These last kept the doors at least partly open for the rest of us. They made discoveries in genetics, found cures for a couple of rare diseases, made advances against other diseases that weren’t so rare—including, ironically, some forms of cancer. But they’d found nothing to help themselves. There had been nothing since the latest improvements in the diet, and those came just before I was born. They, like the original diet, gave more DGDs the courage to have children. They were supposed to do for DGDs what insulin had done for diabetics—give us a normal or nearly normal life span. Maybe they had worked for someone somewhere. They hadn’t worked for anyone I knew.

Biology school was a pain in the usual ways. I didn’t eat in public anymore, didn’t like the way people stared at my biscuits—cleverly dubbed “dog biscuits” in every school I’d ever attended. You’d think university students would be more creative. I didn’t like the way people edged away from me when they caught sight of my emblem. I’d begun wearing it on a chain around my neck and putting it down inside my blouse, but people managed to notice it anyway. People who don’t eat in public, who drink nothing more interesting than water, who smoke nothing at all—people like that are suspicious. Or rather, they make others suspicious. Sooner or later, one of those others, finding my fingers and wrists bare, would fake an interest in my chain. That would be that. I couldn’t hide the emblem in my purse. If anything happened to me, medical people had to see it in time to avoid giving me the medications they might use on a normal person. It isn’t just ordinary food we have to avoid, but about a quarter of a Physicians’ Desk Reference of widely used drugs. Every now and then there are news stories about people who stopped carrying their emblems—probably trying to pass as normal. Then they have an accident. By the time anyone realizes there is anything wrong, it’s too late. So I wore my emblem. And one way or another, people got a look at it or got the word from someone who had. “She is!” Yeah.

At the beginning of my third year, four other DGDs and I decided to rent a house together. We’d all had enough of being lepers twenty-four hours a day. There was an English major. He wanted to be a writer and tell our story from the inside—which had only been done thirty or forty times before. There was a special-education major who hoped the handicapped would accept her more readily than the able-bodied, a premed who planned to go into research, and a chemistry major who didn’t really know what she wanted to do.

Two men and three women. All we had in common was our disease, plus a weird combination of stubborn intensity about whatever we happened to be doing and hopeless cynicism about everything else. Healthy people say no one can concentrate like a DGD. Healthy people have all the time in the world for stupid generalizations and short attention spans.

We did our work, came up for air now and then, ate our biscuits, and attended classes. Our only problem was housecleaning. We worked out a schedule of who would clean what when, who would deal with the yard, whatever. We all agreed on it; then, except for me, everyone seemed to forget about it. I found myself going around reminding people to vacuum, clean the bathroom, mow the lawn … I figured they’d all hate me in no time, but I wasn’t going to be their maid, and I wasn’t going to live in filth. Nobody complained. Nobody even seemed annoyed. They just came up out of their academic daze, cleaned, mopped, mowed, and went back to it. I got into the habit of running around in the evening reminding people. It didn’t bother me if it didn’t bother them.

“How’d you get to be housemother?” a visiting DGD asked.

I shrugged. “Who cares? The house works.” It did. It worked so well that this new guy wanted to move in. He was a friend of one of the others, and another premed. Not bad looking.

“So do I get in or don’t I?” he asked.

“As far as I’m concerned, you do,” I said. I did what his friend should have done—introduced him around, then, after he left, talked to the others to make sure nobody had any real objections. He seemed to fit right in. He forgot to clean the toilet or mow the lawn, just like the others. His name was Alan Chi. I thought Chi was a Chinese name, and I wondered. But he told me his father was Nigerian and that in Ibo the word meant a kind of guardian angel or personal God. He said his own personal God hadn’t been looking out for him very well to let him be born to two DGD parents. Him too.

I don’t think it was much more than that similarity that drew us together at first. Sure, I liked the way he looked, but I was used to liking someone’s looks and having him run like hell when he found out what I was. It took me a while to get used to the fact that Alan wasn’t going anywhere.

I told him about my visit to the DGD ward when I was fifteen—and my suicide attempt afterward. I had never told anyone else. I was surprised at how relieved it made me feel to tell him. And somehow his reaction didn’t surprise me.

“Why didn’t you try again?” he asked. We were alone in the living room.

“At first, because of my parents,” I said. “My father in particular. I couldn’t do that to him again.”

“And after him?”

“Fear. Inertia.”

He nodded. “When I do it, there’ll be no half measures. No being rescued, no waking up in a hospital later.”

“You mean to do it?”

“The day I realize I’ve started to drift. Thank God we get some warning.”

“Not necessarily.”

“Yes, we do. I’ve done a lot of reading. Even talked to a couple of doctors. Don’t believe the rumors non-DGDs invent.”

I looked away, stared into the scarred, empty fireplace. I told him exactly how my father had died—something else I’d never voluntarily told anyone.

He sighed. “Jesus!”

We looked at each o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- The Forbidden Words of Margaret A.: L. Timmel Duchamp

- My Flannel Knickers: Leonora Carrington

- The Mothers of Shark Island: Kit Reed

- The Palm Tree Bandit: Nnedi Okorafor

- The Grammarian’s Five Daughters: Eleanor Arnason

- And Salome Danced: Kelley Eskridge

- The Perfect Married Woman: Angélica Gorodischer

- The Glass Bottle Trick: Nalo Hopkinson

- Their Mother’s Tears: The Fourth Letter: Leena Krohn

- The Screwfly Solution: James Tiptree, Jr.

- Seven Losses of na Re: Rose Lemberg

- The Evening and the Morning and the Night: Octavia E. Butler

- The Sleep of Plants: Anne Richter

- The Men Who Live in Trees: Kelly Barnhill

- Tales from the Breast: Hiromi Goto

- The Fall River Axe Murders: Angela Carter

- Love and Sex Among the Invertebrates: Pat Murphy

- When It Changed: Joanna Russ

- The Woman Who Thought She Was a Planet: Vandana Singh

- Gestella: Susan Palwick

- Boys: Carol Emshwiller

- Stable Strategies for Middle Management: Eileen Gunn

- Northern Chess: Tanith Lee

- Aunts: Karin Tidbeck

- Sur: Ursula K. Le Guin

- Fears: Pamela Sargent

- Detours on the Way to Nothing: Rachel Swirsky

- Thirteen Ways of Looking at Space/Time: Catherynne M. Valente

- Home by the Sea: Élisabeth Vonarburg