eBook - ePub

About this book

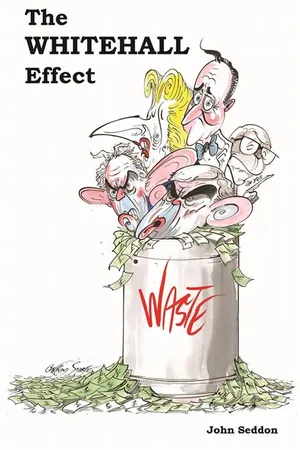

John Seddon explains how successive governments have failed to deliver what our public services need and exposes the devastation that three decades of political fads, fashions and bad theory have caused. With specific examples and new evidence, he chronicles how the Whitehall ideas machine has failed on a monumental scale - and the impact that this has had on public sector workers and those of us who use public sector services.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1: Prelude

Ministers enter management

Back in the day, public administration (rather than ‘public service’) was something conceived as a Weberian bureaucracy, honest and fair, funded by the state, treating all citizens alike, governed by clear procedures and rules, where role and position in the civil-service hierarchy conferred the power to behave within a clear legal framework. As the economy grew, public services grew with it. With the advent of an economic shock in the early 1970s, public-sector reform began to be a political priority. Public services were increasing demands on national resources, something that was perceived as no longer affordable in the long term.

People argued — as they do today — that expenditure was out of control because of statutory entitlements to benefits and services. Escalating cost was also attributed to inefficient ways of working. There had been costly debacles, for example ballistic missiles forecast to cost £50m but eventually totalling over £300m (in fact a trivial waste compared to recent IT-related failures). Concorde, dubbed the flying white elephant, only took off after consuming well over a billion from the public purse1. Many people argued that the cause was civil service incompetence in managing resources.

Margaret Thatcher (1997-1990)

Into this developing maelstrom entered Margaret Thatcher, who, it has to be said, mixing metaphors, stirred up the hornet’s nest by taking the most resolutely negative view of the public sector of all British prime ministers. She rejected as “a socialist ratchet”2 the post-war consensus of the state as a benevolent provider of public services, was alarmist about the costs associated with universal welfare benefits and, inspired by the economist Friedrich Hayek, argued that any increase in the role of the state would destroy free enterprise by draining resources away from wealth-creating activities3.

Thatcher pointed to growing numbers of “wealth-consuming” public sector jobs and believed civil servants acted in their own “producer” interests (“we pay through the nose in prices and taxes and take what we are given”4). She scorned public-sector leaders for being no good — otherwise they’d be working for the private sector5 — and took the view that where public services couldn’t be privatised, the preferred option, their managers should take lessons from the private sector. This was at a time when private-sector companies had begun to construct call centres and centralise ‘back-office’ activities in pursuit of the assumed benefits of economies of scale.

Thatcher reckoned that private-sector service organisations’ focus on customer service would bring a breath of fresh air to cumbersome public-service bureaucracies, making them more citizen-centric. Following Hayek, Thatcher introduced the concept of choice, treating users of public services as customers. If people weren’t free to choose what they consumed, she reasoned, power would inevitably accrue to politicians, bureaucrats and providers of services instead6.

The central driver was expenditure: in other words cost. ‘Doing more with less’ became a mantra. The public sector was encouraged to adopt ‘proven’ private-sector methods, to compete on price, to deal with labour indiscipline, to fight trade unions, to develop stronger financial controls and to employ information technology to drive down service costs.

Within days of taking office Thatcher appointed Derek Rayner, then joint managing director of Marks & Spencer, to spearhead a drive against waste and inefficiency. In her first year she established an ‘Efficiency Unit’ which brought government departments before her to be scrutinised for ways of saving money.

In 1980 came Compulsory Competitive Tendering (CCT). CCT opened up public-sector contracts to private companies by obliging local authorities to put services out to tender. Initially CCT was limited to highways and buildings maintenance and minor building work, but in 1988 it was extended to include refuse collection, street and building cleaning, schools and welfare catering, meals-on-wheels, and grounds and vehicle maintenance. From 1989 CCT also covered council sports and leisure services. In 1992 it was broadened further to include professional, financial and technical services, and then in 1993 it was extended to many of the activities in housing management.

The intervention that was to have the most profound effect on public-service operations under successive governments was the creation of the Audit Commission in 1983. Michael Heseltine, a secretary of state in Thatcher’s cabinet who had made his name (and money) as a private-sector media baron, was the architect. The idea was to replace district audit functions, whose purpose had been to audit financial probity, with an organisation that would not only audit spending but would also evaluate public-sector organisations’ operational performance. Audit now had the remit to roam as consultants in performance improvement; perhaps not coincidentally, the Commission’s first two chief executives had previously worked for McKinsey.

In 1988 Thatcher proposed turning half of Whitehall into ‘agencies’ with the aim of freeing government departments from central control to focus on ‘delivery’ against frameworks including policy, targets and outcomes, agreed with ministers. While ostensibly free to deliver, the new agencies were to be subjected to a “constant and sustained pressure for improvement”7. The waves of agency creation continued right through the 1990s. Within a decade three-quarters of civil servants were employed in agencies.

In 1989 Thatcher turned her attention to the health service. In 10 years her government had increased health spending by 40%8, yet in her view the NHS remained an inefficient and patient-unfriendly monolith. This could not continue — the more so as demand for health services would only increase as the population aged. To cope with this, she wanted to “work towards a new way of allocating money within the NHS, so that hospitals treating more patients received more income. There also needed to be a closer, clearer connection between the demand for health care, its cost and the method for paying for it”9.

Her remedies were establishing self-governance in NHS trusts and encouraging private-sector delivery of services. The mantra was that the money should follow the patient, “simulating within the NHS as many as possible of the advantages which the private sector and market choice offered, but without privatisation”10.

John Major (1990-1997)

Thatcher’s successor John Major took a more conciliatory line on public-sector reform. He was less negative about public-sector management, acknowledging that while many public services were “excellent” others could be “patronising and arrogant”, run more for the “‘convenience of the providers than the users”11. Major was not as strident as Thatcher about privatisation, believing that public-sector services could be improved while remaining in state control, but he was just as fervent about the need for reform. Consistent with his predecessor’s criticism of “producer-focused” public-sector managers, he wanted providers to be more service-orientated, a shift that he believed could be encouraged by the empowerment of consumers.

Major believed targets, standards and league tables would serve as surrogates for competition, creating pressure to improve. The ideas were encapsulated in the Citizen’s Charter. Major instructed all ministers to develop plans for improving service performance. He set up a unit within government — the Office of Public Service Standards — to cajole ministers and review their plans and achievements. To recognise achievements he created the Charter Mark, an award for service excellence.

Major saw independent inspection as a vital tool in the armoury of reform, reinforcing the role of the Audit Commission and introducing the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) to drive up standards in education.

Targets and standards were quickly adopted by the Audit Commission, magnifying its influence on public-service operations. Adherence to targets and standards were central to Audit Commission reports, evaluating the performance of councils against centrally directed criteria12. Likewise the Next Steps Agencies initiated under Thatcher were obliged to adopt Major’s charter ideas, in his view increasing transparency and accountability.

Tony Blair (1997-2007)

Elected in 1997, New Labour’s Tony Blair was more technocratic in his zeal for reform than his Conservative predecessors. He agreed with Thatcher and Major on the issue of ‘producer-driven’ services, arguing that ‘public-sector ethos’ was a cover for poor performance and that ‘choice’ would drive improvement. Blair labelled reform as ‘modernisation’, clearly signalling his belief that the public sector was behind the times and only the private sector had the know-how to bring it up to date. He felt that previous Conservative administrations had achieved little in terms of genuine reform, leaving in place inefficient monopolistic public services that were still hurting the people they were supposed to help — the poor.

Blair’s mantra was ‘efficiency’. He scrapped the ‘compulsory’ in CCT and emphasised instead that procurement should focus on ‘value-for-money’13. Pressing forward with reform of the health service, he oversaw the establishment of ‘foundation hospitals’ which, like his predecessors’ trusts, set out to link expenditure with performance.

Blair expanded the inspection regime, establishing the Healthcare Commission, the Commission for Social Care Inspection and Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, and extended Ofsted’s remit to cover children’s services. He also expanded the Audit Commission’s inspection activities in local government and extended its reach to housing associations. These activities were dovetailed with National Service Frameworks, Public Service Agreements and Local Area Agreements. In 2002 the Audit Commission started to use Comprehensive Performance Assessments, the results of which were published as league tables. In Blair’s era the Audit Commission was expected to join with government in devising ways to effect real change, beginning a relationship with government that meant it was no longer independent, but more an instrument of change14.

Under Blair, the internet was co-opted into the modernisation programme. An Electronic Service Delivery (ESD) target stipulated that one quarter of dealings with government should be digitally enabled via television, telephone or computer. To that end in 2001 the government issued detailed guidance notes (“Modern councils, modern services — access for all”15) that local councils were expected to follow to exploit the ‘e-revolution’. Digital services promised the benefits of efficiency — cheaper transactions. The guidance, following Thatcher’s and the private sector’s emphasis on economies of scale, was a compendium of ‘solutions’ developed by the big consultancies and IT firms: access to services via call centres and digital ‘channels’, back offices where services would be delivered more ‘seamlessly’, tied together with new IT systems, essential for the programme to work. The ESD target guidance anticipated that councils would “take full advantage of the strategic opportunities available with local and private sector partners”16.

Blair’s ministers followed this agenda. For example, Home Secretary David Blunkett obliged police forces to create regional call centres and Frank Dobson as Health Secretary set up NHS Direct to deliver medical services over the phone. Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott initiated the development of regional call centres for the Fire and Rescue Service.

In 2001 Blair instituted a No 10 ‘Delivery Unit’ with a brief to oversee and monitor performance improvement. Like Thatcher’s Efficiency Unit and Major’s Office of Public Service Standards the Delivery Unit’s remit was to review and challenge plans for improvement, but it differed in being more programmatic and structured. Its leader, Michael Barber, later to join McKinsey, coined the term ‘deliverology’ to describe what he called the “science of delivery”. The delivery unit sat alongside a strategy unit, set up to plan strategy and develop ideas for reform.

Blair employed Sir Peter Gershon, recruited from the private-sector, to run the Office of Government Commerce overseeing procurement across Whitehall. In 2004 his eponymous report put at £20bn the savings that could be made by improving procurement, standardising policies and procedures and simplifying, standardising and sharing support services such as HR, IT and finance in ‘back offices’, with these initiatives to be benchmarked across the public sector17.

It was Gordon Brown, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, who invented the phrase “invest to save”. What it meant was that local authorities could use cash from Whitehall to create call centres and back offices. Jim Murphy, minister at the Cabinet Office, claimed that sharing services would realise efficiency savings of up to 20%18. The wave of sharing services in central and local government began.

Blair, like his predecessors, believed in the importance of ‘choice’ and competition, arguing that competition was essential if choice is to work. Competition, he believed, would give producers a strong incentive to make better use of resources and drive them to devolve power to service users. Blair’s administration coined the term ‘double devolution’ — devolution that went beyond local authorities and passed power instead to local communities.

At the end of his term of office Blair summarised his approa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Prelude

- Part 1: The industrialisation of public services

- Part 2: Delivering services that work

- Part 3: Things that make your head hurt

- Part 4: Ideology, fashions and fads

- Part 5: Change must start in Whitehall

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Whitehall Effect by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.