eBook - ePub

Rooting for Rivals

How Collaboration and Generosity Increase the Impact of Leaders, Charities, and Churches

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Rooting for Rivals

How Collaboration and Generosity Increase the Impact of Leaders, Charities, and Churches

About this book

Faith-based organizations are sometimes known for what we're against--and all too often that includes being against each other. But amid growing distrust of religious institutions, Christ-centered nonprofits have a unique opportunity to link arms and collectively pursue a calling higher than any one organization's agenda.

Rooting for Rivals reveals how your ministry can multiply its impact by cooperating, rather than competing. Peter Greer and Chris Horst explore case studies illustrating the power of collaborative ministry. They also vulnerably share their own failures and successes in pursuing a kingdom mind-set. Discover the power of openhanded leadership to make a greater impact on the world.

"I love the African quote, 'If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.' I'm grateful to Peter Greer and Chris Horst for celebrating Christ-centered teamwork and collaboration in Rooting for Rivals."--RICHARD STEARNS, president of World Vision U.S. and author of The Hole in Our Gospel

Rooting for Rivals reveals how your ministry can multiply its impact by cooperating, rather than competing. Peter Greer and Chris Horst explore case studies illustrating the power of collaborative ministry. They also vulnerably share their own failures and successes in pursuing a kingdom mind-set. Discover the power of openhanded leadership to make a greater impact on the world.

"I love the African quote, 'If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.' I'm grateful to Peter Greer and Chris Horst for celebrating Christ-centered teamwork and collaboration in Rooting for Rivals."--RICHARD STEARNS, president of World Vision U.S. and author of The Hole in Our Gospel

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rooting for Rivals by Peter Greer,Chris Horst,Jill Heisey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Ministry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

CHAPTER 1

Our Uncommon Unity

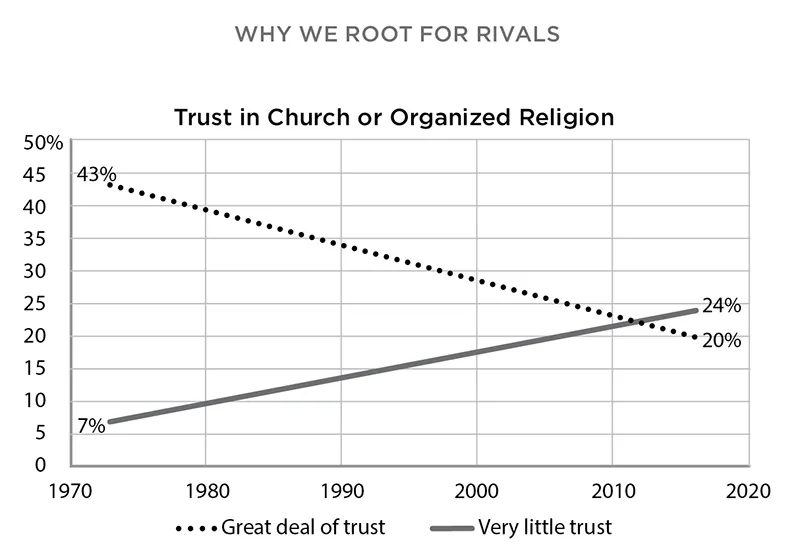

For faith-based organizations, the landscape is rapidly changing. The Pew Trusts assesses confidence Americans place in our fifteen largest public institutions. The military and small business rank highest. Congress and big business rank lowest.1

When they began doing the survey in 1973, 43 percent of Americans said they placed a “great deal” of trust in “the church or organized religion.” Today, just 20 percent do. In 1973, just 7 percent said they placed “very little” trust in the church. Today, 24 percent do. Over the past few decades, the percentage of Americans who trust the church has been cut in half. And the number of those who strongly distrust the church has more than tripled.

Governmental pressure has also increased. Over the last decade, Pew Trusts states that the United States has moved from a country of “low” religious freedom restrictions to “moderate” restrictions.2 Faith-based mentoring organizations, homeless shelters, universities, and international relief and development organizations feel this surge in suspicion.

Some of the increasing mistrust results from changes in our culture, but some is a direct indication of our own state. The world has seen celebrity pastors, faith-based nonprofit leaders, and priests abuse their power, fall into moral failure, and purvey their influence for unseemly political aims—breeding well-deserved suspicion and skepticism. As Beth Moore wrote, “The enemy’s hope for Christians is that we will either be so ineffective we have no testimony, or we’ll ruin the one we have.”3

Trust in faith-based organizations is also eroding for a subtler but equally dangerous reason: When our organizations embody a rugged individualism and fuel division between people intended to be united in mission, we deserve the world’s skepticism. When we act like we’re entirely disparate organizations—each responsible for ourselves alone—it confuses the culture around us. When we concern ourselves only with our own organization’s success, the world wonders, Are you on the same team or not? Are you allies or rivals? Why such division?

United We Stand?

In our culture, division runs rampant. We disagree—often passionately—on politics, church, sexuality, science, and so many other issues.

We feel the tension in our homes when we gather at the Thanksgiving table or around the tree at Christmas. We hear the division in daily shouting matches on the news. We scroll past it—or engage in it—on social media. Every year, we are becoming more and more divided, with several research studies concluding our country has not been this polarized and divided since the Civil War.4

And within Christian faith-based organizations, we feel it acutely. Intuitively, we know we’re supposed to be on the same team, but reality tells another story. If we are at all unified, it’s probably in our agreement that we are a nation and a Church divided. Fragmented, really.

Guidestar lists nearly eighty-five thousand nonprofit organizations in the United States that self-identify as Christian.5 “The Center for the Study of Global Christianity counts forty-five thousand denominations around the world,” wrote Jennifer Powell McNutt in Christianity Today, “with an average of 2.4 new ones forming every day. The center has an admittedly broad definition of denomination, but even a dramatically lower count will be absurdly high in light of Jesus’s prayer in John 17 that we all might be one.”6 In 1 Corinthians, Paul chastises Christ’s followers in Corinth who have split into four groups: “Is Christ divided?”7 What would he think of forty-five thousand?

John 17—Jesus’ longest recorded prayer in Scripture—rebukes the present situation of the Church. Its main theme is the unity of Jesus’ followers. He prays “that [we] may become perfectly one,” so that the world may know the Father’s love.8 The implication is that our witness to the world hinges on our unity.

“Christ’s prayer for unity and endurance is formed, uttered, and accomplished at the greatest hour of trial in all of redemptive history,” writes K. A. Ellis. “At this critical juncture there is one relationship on his mind, and it is ours.”9

Jesus says our oneness is the way that others will identify us as His followers: “By this all people will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another.”10 Yet as clearly as Jesus prioritized unity among His followers, we are quick to disregard it. Our natural inclination is to splinter. For Protestants, protest is in our very name. In our tribe, when disagreements emerge, we split.

There are important and legitimate reasons for churches to split and organizations to define strong boundaries. There is a time to separate. But there is an opportunity for Christians to find unity even in disagreement. There is an opportunity for us to build bridges across the lines that divide us. In this bright age of individualism, intellectual property rights, and splintering denominations, our unity in Christ is fading.11 But, “How good and pleasant it is when brothers dwell in unity!”12

The unity of God’s people is the first reason we can and should root for our rivals. And when we consider the power and beauty of what we hold in common, sometimes our divisions seem almost trivial.

What Color Is Your Buggy?

I (Peter) live in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, where tourism—a booming local industry—is driven by a fascination with the Amish. Visitors arrive to observe this community, intentionally set apart from technology and modern dress. Tourists dine in Amish homes, take buggy rides, and tour working farms. In some ways it’s like visiting Colonial Williamsburg and seeing a snapshot of life frozen in time, but these are not actors. Very real convictions motivate their eschewal of modernity.

The modern-day Amish have their roots in sixteenth-century Europe, where their ancestors faced extreme religious persecution. They were so strong in their convictions that thousands were martyred, being burned at the stake, drowned, and beheaded. The Amish arrived in North America in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Shaped by their experience of persecution as well as their understanding of Scripture, they established a life and culture set apart from the larger society.

Soon it wasn’t enough to be separate from the outside world. Even within the Amish community, schisms formed. Once they were no longer persecuted, they seemed to turn against each other. What most Lancaster County tourists don’t realize when coming to see “the Amish” is that they are encountering many distinct groups.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were three or four affiliations. By 2012, there were more than forty, not including smaller subgroups. Rifts among the groups have been caused less by issues foundational to the faith than by matters such as the use of buttons and zippers. Churches have split based upon a disagreement between those who wear two suspenders versus one suspender, and then split again over whether the suspender should fall across the right or left shoulder.13

The division can even be spotted in the buggies. While driving through Amish communities, you may come across black, brown, yellow, and white buggies. Each color is an external sign stating, “We are not like them.” It signifies a separate Amish or Mennonite church faction. The Byler Amish are distinguished by their yellow-roofed buggy, the Nebraska or Old School Amish for their white-topped buggy, and the Peachy Amish for their all-black buggies.14

“You have to get the most powerful magnifying glass to see the hairs that resulted in the splits,” reflected Charlie Kreider, a friend who grew up in the Mennonite Church in Lancaster County.15 Disagreements over the letter of the law run through the paint, proving that just about anything can drive a wedge between families and friends of the same faith conviction.

Our propensity to divide runs counter to Jesus’ prayer for unity and propels us to root against our rivals. And these somewhat arbitrary distinctions can have deadly consequences.

Calipers, Nursery Rhymes, and Emblems

Several times over the past few years, I (Chris) have visited the Kigali Genocide Memorial in Rwanda. The first exhibit in the memorial displays an ominous image. At first glance, the picture is innocuous enough. It is far less grisly than many of the pictures throughout the rest of the memorial. But it is far more haunting.

In the picture, a Rwandan man sits in an examination room. A Belgian examiner measures the width and length of the man’s nose with a metal caliper. He then measures the eyes of the Rwandan man, contrasting and comparing the shape and size of the man’s eyes to a chart of various cultural eye shapes.

We now know that following World War I Belgian colonizers sent scientists to Rwanda, wielding “scales and measuring tapes and calipers, and they went about weighing Rwandans, measuring Rwandan cranial capacities, and conducting comparative analyses of the relative protuberance of Rwandan noses.”16

These tools, though far less violent than the machetes and guns used to perpetrate the genocide, are far more barbaric. They were used to draw distinctions and grant favored status to Rwanda’s Tutsi minority, who were seen as more evolved (i.e., more European), while the majority Hutus became oppressed and increasingly resentful. When walking through the genocide memorial, jarring images of soldiers and militants line the walls. But it is this seemingly benign activity—a scientist wielding a caliper—that created division and preceded the slaughter of nearly one in ten Rwandan people.

First the calipers and scales were dispensed. Soon the common physical appearances of the Hutus and Tutsis were codified. Then, beginning in 1933, government officials mandated Rwandans record these differentiations between Hutus and Tutsis on identification cards. As the genocide unfolded, perpetrators used these cards and physical differentiations to separate neighbors from each other. To separate friends and groups of students from their peers. To determine who lived and who died.

At the memorial, the second floor exhibits the terrible realities of genocides committed across the world and across history. In each case, division precedes violence. The Nazis forced Jewish men, women, and children to adorn their clothing or an armband with the Star of David. Turkish military and government officials organized the genocide against hundreds of thousands of Armenians who were identified as Christians on their national identification cards.17

My family recently lived in the Dominican Republic for a few months. There, we learned about the history of Hispaniola and some of the horrific massacres carried out against ethnic groups on the island. In 1804, Haitian dictator Jean-Jacques Dessalines murdered all Fr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Endorsements

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part One

- Part Two

- Notes

- About the Authors

- Books by Chris Horst and Peter Greer

- About HOPE International

- Back Ad

- Back Cover