![]()

I

FOUNDING FATHERS: SLAVEHOLDERS AND ADULTERERS

American history started as it meant to go on – as big and bold in its faults as in its virtues. Along with the glory there was graft, including dope-smoking and sexual shenanigans: the Founding Fathers were colossal figures, but with feet of clay.

With Washington burning and British invaders threatening the White House in 1812, Dolley Madison rescued the Declaration of Independence (pictured). She also saved a celebrated portrait of America’s first President, George Washington (pictured).

‘Liberty, when it begins to take root, is a plant of rapid growth.’

America’s first four Presidents had all been signatories to the Declaration of Independence in 1776. The United States quite literally wouldn’t have existed without them. They were great men – no-one would question that. But even great men may have flaws – and George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison were no exception. When you add the immense confusion of the times into the general moral mix, you see how great the temptations must have been: in a situation without precedent, these men were making it up as they went along.

They had, after all, just staged the first revolution of the modern age, and after such convulsions it takes a nation time to settle down. (Thankfully, the sins of the Founding Fathers were to pale into insignificance beside those of the French Revolutionaries, whose Reign of Terror, 1793–4 cost up to 40,000 lives.) When we see them now, in patriotic paintings, we see a group united in noble resolution, but it’s really only in hindsight that this is so. They were courageous; and for certain, they fought together, but they had to overcome a great many reservations and rivalries. They had differences of opinion and competing ambitions; they came from a variety of backgrounds and couldn’t always understand the attitudes of their comrades. There was a huge amount at stake: if the United States was as yet an insignificant little slip of a nation, it already had a superpower’s sense of destiny.

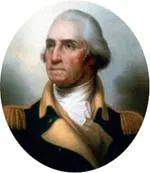

GEORGE WASHINGTON, 1789–97

George Washington’s place in the pantheon of heroes is secure, so there can be no harm in considering some of his shortcomings. Which is just as well, given that some of the things he did in the course of his career wouldn’t necessarily have gone down so well with those who oversee our representatives’ conduct nowadays. No one’s ever suggested he was some kind of monster in the manner of Stalin or Genghis Khan; neither is there any serious question as to whether he deserves the honour due to his nation’s founder. It’s just that, sad to say, his reputation remains tarnished by behaviour which somehow doesn’t seem quite worthy of such a man.

And it goes well beyond the great cherry-tree scandal of his childhood years. That is one crime of which, the historians say, he almost certainly wasn’t guilty: Mason Weems seems to have made this story up, for the sake of colour and moral instruction, when he wrote his myth-making biography of the great man in 1800. It’s a memorable story, of course, and as far as it goes it’s not implausible – the kind of thing that might easily have happened, even if it didn’t.

As craggy as his Mount Rushmore face, America’s first President looks the picture of integrity in this contemporary engraving. In some ways, sadly, the reality fell short of the idealized image.

But many of us who ‘cannot tell a lie’ at six find that it gets easier as we get older – partly because we find newer, more creative ways of misleading others. We have no reason to believe that, as President, Washington ever stood up and spoke untruthfully to the people or their representatives. Even so, he was dogged by what we would nowadays call the ‘character issue’.

The Padding Problem

‘First in war’? Undoubtedly. It’s easy to forget how close to final defeat the colonists came after the reverse at Brandywine in 1777 and the appalling winter that followed at Valley Forge. Washington saw them through, and emerged from the fighting to be ‘first in peace’ – a shoo-in as the United States’ inaugural President – and ‘first in the hearts of his countrymen’ for all time. But did he have to be first with his expenses claims as well? Especially when he’d made such a self-sacrificing performance of agreeing to lead the Continental Army without pay? ‘As no pecuniary consideration could have tempted me to accept this arduous employment, I do not wish to make any profit from it,’ he assured a grateful Congress.

Little did they know what they were letting themselves in for. If Washington was a doughty warrior, he was also a filer of expense claims on an epic scale. Nothing was too good for the nation’s protector: a band to play to him on his birthday? A fancy leather letter-case? If Washington wanted it, he got it – and Congress couldn’t bat an eyelid. In his eight years as commander, from 1775 to 1783, he claimed just under $450,000 ($9.4 million today) in personal expenses – an incredible sum in eighteenth-century terms.

With her rose and her roguish glance, Sally Fairfax shows the face, the figure and the personality that captured Washington’s heart. But how much more was there to their relationship really than a high-flown crush?

George Washington chats with a (white) farmhand as the harvest is brought in on his estate. It’s easy to forget, presented with this idyllic scene, that the black workers are all slaves and that the democracy he’d helped found was firmly rooted in racism and oppression.

And it wasn’t just that he was extravagant: many of the claims had little or no documentation – some of these were for tens of thousands of dollars at a time. Washington became masterly in his wielding of weasel-words like ‘sundries’, whilst he makes the use of ‘etc’ into something of an art form. Other claims were for ‘loans’ to friends – never repaid: was Washington looking after his supporters at the state’s expense, or lining his own pockets? Sometimes the latter conclusion is just about impossible to avoid. Could he really have spent $800 ($23,000 today) on saddles?

His greed was all-consuming – not just financial avarice but rampant gluttony. Whatever the circumstances, the commander of the Republican army always insisted on eating (dare one say it?) like a king. Well into the winter at Valley Forge, when his troops in their thousands were literally starving, he was banqueting on beef, veal, pigeons, chickens, oysters … you name it; and washing it down with the finest imported wines.

Obscene? Well, yes – though Washington genuinely doesn’t seem to have seen any inconsistency; and there’s no doubt that he was conscientious in his own way. He threw himself into his general’s duties, working round the clock to keep up morale among his men. He seems to have taken literally the idea that his own welfare as leader was paramount; the well-being of his army would ultimately flow from that.

Not surprisingly, when the war was over, and he had been asked to be his country’s President, Washington offered to carry on serving ‘unpaid’. Equally unsurprisingly, Congress quietly turned him down, awarding him a $25,000 ($520,000 today) salary instead. A princely sum, but a bargain after the ‘pro bono’ bonanza of the war years.

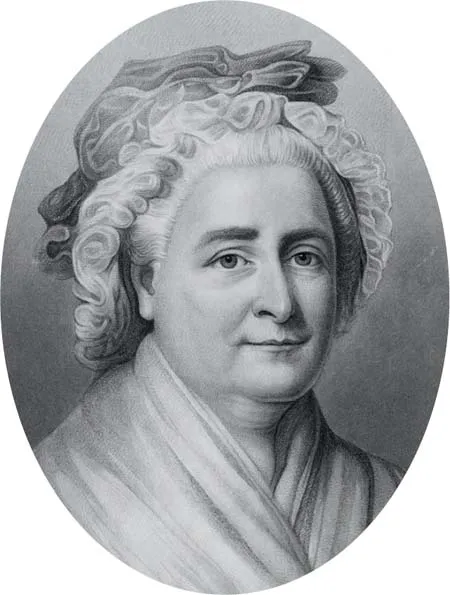

Marriage and Martha

Martha Dandridge Custis was a widow in her twenties when she first caught Washington’s attention – though it’s widely believed that the future President had eyes only for her estate. From her late husband, Daniel Parke Custis, she had inherited extensive properties in land and slaves at White House Plantation, New Kent County, Virginia. Washington was widely believed to be in love with a certain Sally Fairfax: he wrote her romantic (if ambiguous) letters, in which he confessed himself a ‘votary of Love’. Local gossips were in no doubt that they had consummated their affair. Many modern historians are more doubtful. Were the tongue-waggers putting two and two together and making five? Or are the academic sceptics trying too hard to defend the honour of the Founding Father? In the end, we can only follow our own hunches here.

First in the heart of her husband? Martha Dandridge Custis may have become her country’s first First Lady, but some historians have suggested that she came a poor second to Sally Fairfax in Washington’s affections.

Whatever the attraction, Washington having married Martha in 1759, she became America’s first First Lady 30 years later. A loving wife and loyal companion, she deserves credit for the time she spent on campaign with her soldier husband – though, as we’ve seen, conditions for Washington and his staff weren’t exactly Spartan.

Whatever reservations we might have about his character, Washington’s courage and resourcefulness weren’t in doubt. He’d established his military reputation as a brave young captain in the French and Indian War of 1754–63.

There is another rumour that puts us on even shakier ground – that future Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton was Washington’s son: he was born in 1755 (or, more likely, 1757) on the island of Nevis in the West Indies. His acknowledged father James Hamilton and mother Rachel Fawcett Lavien both belonged to wealthy planter families there: we have no reason to believe that Washington was in Nevis at the relevant time – or, for that matter, ever. It’s true that he’d been in Barbados accompanying his brother Lawrence when he was recuperating after illness, but this had been a few years before – and some 579km (360 miles) away. It’s true, though (and very likely a source for a great deal of the speculation) that when the young Alexander joined Washington’s staff, the General said he loved him ‘like a son’. Some have even speculated on the existence of a homosexual relationship between them – this is at least more likely than that the younger man was the elder’s son.

Sleeping with the Enemy?

In 1776, Thomas Hickey, a member of Washington’s bodyguard was arrested in New York: it was alleged that he was a British loyalist, and that he’d conspired to kidnap his commander. The committee charged with investigating the case was alarmed to find witness after witness confirming in the course of its inquiries that Washington was accustomed to visit a certain house beside the Hudson River late at night, his appearance always heavily disguised. It seemed that the general had a mistress, Mary Gibbons, of whom he was ‘very fond’ and whom he ‘maintained … very genteelly’ there. More shocking than the moral question was the claim that Mary had been accustomed carefully to going through her lover’s papers while he slept and copying items of special interest to be sold on to the British. Hickey was hanged regardless, but the full facts of the conspiracy (if that’s what it was) were never discovered. Was Washington really the victim of a Loyalist Mata Hari, or was this story just a smear put about by his pro-British enemies?

An indispensable aide during the Revolutionary War, Alexander Hamilto...