![]()

Asniper is one of the most highly skilled personnel in any military force. He fires his weapon rarely, but those few shots make a profound difference. Whether protecting friendly forces from enemy marksmen or stalking high-value enemy personnel, the sniper is always vigilant, waiting for the perfect moment to shoot.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Most people think of snipers as individuals who can shoot with great accuracy. This is certainly true, but there is much more to sniping than marksmanship. Perhaps a better definition of the sniper is a person who has the ability to greatly influence events around him with a single shot.

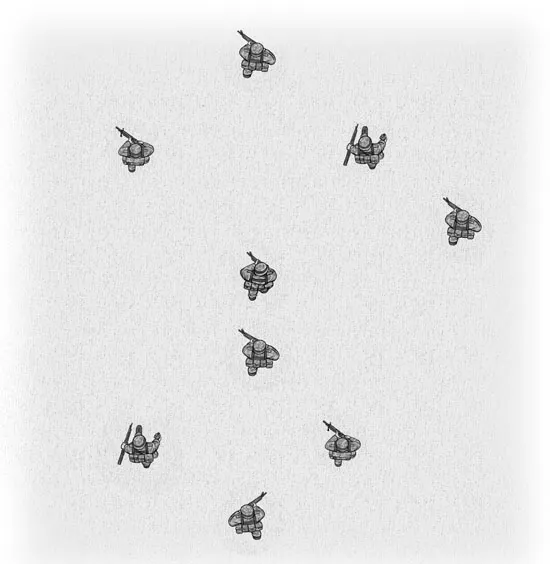

This in turn assumes a number of things. The sniper must have the ability to get into position to take the shot, and to remain there undetected until it is time to shoot. He must also be able to extract himself safely afterwards. He needs to be able to identify a valuable target and set up a shot that has a good chance of success, taking into account environmental factors like wind and humidity. He must be patient enough to wait for the right moment, and dedicated enough to make the shot without hesitation when the time comes. And then, of course, he must be able to hit the target. There are times when snipers will engage whatever targets present themselves, such as enemy infantrymen. However, this is something of a waste of their abilities. Any soldier can fire at the enemy, and while casualties inflicted on a hostile force will wear down its ability to fight, most casualties are ordinary infantrymen and thus affect the course of an engagement only marginally.

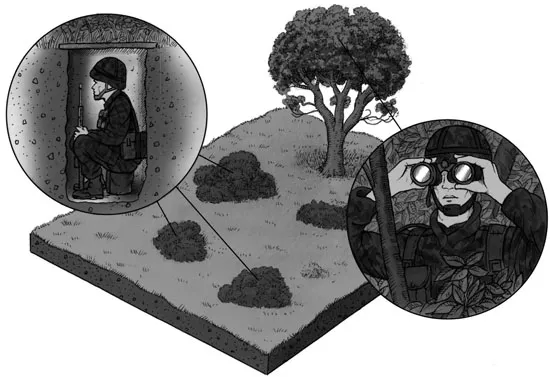

Sniper Hides

Concealment lies at the heart of sniping technique. Whether using an elaborate hide or taking advantage of naturally occurring concealment, the sniper must remain unseen while he observes the enemy and sets up his shot.

Target Acquisition

A sniper will get one clear shot at an infantry squad before the survivors take cover. He must select the target that will cause the greatest effect, which will usually be the squad leader. A sniper who is well versed in standard infantry doctrine will know which of these soldiers is in command.

A sniper is trained to select a target whose loss will have a greater effect on the enemy than that of a single infantry soldier. Officers, communications personnel and heavy weapons crews are all high-value targets: their loss degrades the enemy’s performance significantly. Eliminating a leader, or depriving him of the ability to give orders, can throw a force into confusion and prevent it from calling in support from aircraft or artillery.

Heavy Sniper Rifles

A 12.7mm (0.5in) bolt-action rifle, the Model 500 is in service with the US Navy and Marines. It is a single-shot weapon and slow to reload as the bolt is entirely removed to chamber each new round. The free-floating barrel is supported by a bipod on the weapon’s forearm.

The Steyr HS .50 has a heavy muzzle brake to reduce the recoil generated by its powerful 12.7mm (0.5in) calibre round. A five-shot magazine-fed version is now available.

Higher-level personnel, such as senior commanders or important specialists, are not usually found close to the combat area. A sniper may be able to infiltrate into an area where a conventional force would be quickly detected, and thus has the potential to eliminate key enemy personnel. The loss of a popular commander can demoralize enemy personnel; killing an efficient officer can weaken the whole force.

Snipers can also destroy enemy equipment. Anti-materiel sniping can be used to deprive the enemy of communications or radar equipment, or light vehicles, and weapons can also be targeted. A machine gun whose gunner is disabled can be used by another soldier, but one that is damaged by an armour-piercing round striking the receiver is inoperable in anyone’s hands.

Counter-Sniping

The best counter to an enemy sniper is another sniper, and counter-sniper operations are an important part of the sniper’s role. A skilled sniper can recognize the places that an enemy might hide by considering where he would position himself; he also possesses both the observation skills and the patience to watch for stealthy movement.

Counter-sniping

Counter-sniper work is one of the most important tasks undertaken by snipers. Often this means passing up other targets in order to remain concealed. Eliminating a skilled enemy sniper is worth letting most other potential victims go.

He also has the ability to eliminate the enemy sniper from a distance rather than having to move in a patrol to find him. This reduces the exposure of friendly troops to sniper fire and also makes it less likely that the enemy sniper will slip away once the hunt begins to close in.

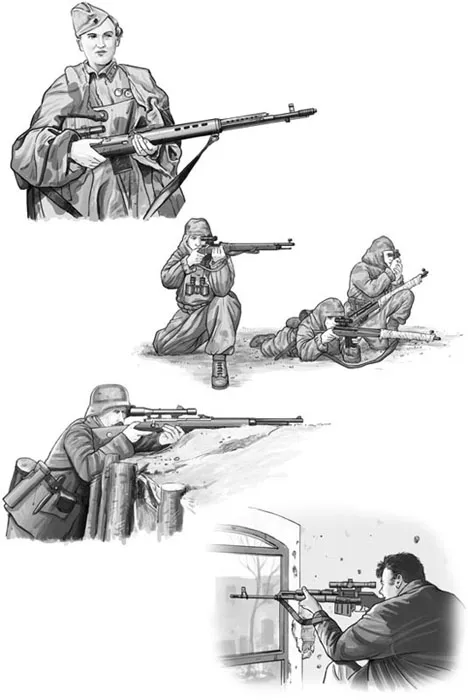

Law Enforcement Applications

Sniping is often considered to be an exclusively military activity, but there is also an important role to be played in law enforcement. Military snipers generally shoot from much greater distances than their colleagues in law enforcement, but the principles are, in general, much the same. A law-enforcement sniper may be called upon to disable gunmen who have taken hostages or who otherwise pose an imminent threat to civilians or police officers; but he will usually be required to wait until other, less terminal, means of resolving the situation have been attempted.

This means that sometimes the law-enforcement sniper will have to be ready to shoot at an instant’s notice but must wait for a command or for an action on the part of the target that necessitates an immediate shot. This is one difference between military and law-enforcement sniping: a military sniper shoots when the time is right for the shot, while a law-enforcement sniper must often shoot when the circumstances necessitate it. There is no guarantee that the two will coincide.

Law-enforcement snipers also engage in anti-materiel work. The engines of vehicles or boats can be shot out to prevent a suspect from fleeing, or in some cases a weapon can be engaged to render it useless. This requires very precise shooting, as these personnel often operate in an environment where innocent people are nearby, and so must avoid collateral casualties.

![]()

Snipers have developed from the marksmen of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries to the highlytrained military professionals of the modern era.

1

Sniping is an essential part of modern infantry doctrine, but there have been times when the art was neglected to the point where painful lessons had to be entirely re-learned.

A Brief History of Sniping

The use of projectile weapons to kill or disable a target from a distance predates history. Early hunters learned to throw a spear or shoot a bow to take down prey, and in the case of large or dangerous creatures this required a precise first shot in order to ensure that the prey did not flee or attack the hunter. The same skills were useful in dealing with human threats, such as members of a rival tribe.

As organized warfare developed, the emphasis shifted from the use of hunting skills to specialized military techniques, including close-quarters fighting with swords, maces and axes as well as the massed use of archers. The latter would sometimes shoot together in a volley aimed at an area rather than an individual, but they would often take aimed shots at closer range.

Archers honed their skills both in formal practice and in the hunt, and were often extremely proficient marksmen capable of hitting an enemy in the head at 50m (164ft). This was a necessity in an age where enemy infantry were protected by shields and metal body armour. Archers were by no means ‘snipers’ as such, but their mode of combat called for a high level of marksmanship and some of the skills of a sniper, such as accounting for wind and atmospheric conditions.

Early Firearms

Ironically, as firearms came to dominate the battlefield, the level of marksmanship required of most individual soldiers declined. Early smoothbore matchlock and flintlock firearms were incapable of great accuracy and were most effective when fired in massed volleys at fairly close range. The target was a block of enemy troops, not an individual, and still most shots missed.

Early rifles were slow to load, making them inappropriate for issue to the rank-and-file of most armies. The majority of soldiers received only brief instruction in how to load, point and fire their weapons on command, and few armies spent much on ammunition for live firing practice. Thus there was no point in giving the average soldier a rifle, when he lacked the skills to make much use of it. Instead, he was given a smoothbore weapon, which could make up for lack of accuracy with volume of fire.

Yet even at this low point in the history of marksmanship, there were those who excelled. These individuals developed a high level of skill from hunting in civilian life, and took their marksmanship to war. Whether fighting as irregulars or militia, or as part of an organized regiment of troops, these early marksmen could hit individual enemies at distances where a musket shot would be pointless.

Flintlocks and Matchlocks

Accurate shooting with early firearms was a difficult business even without considering the vagaries of smoothbore weapons. Pulling the trigger caused the spring-loaded lock to move forward, scraping the flint against a striking plate or bringing a length of slow-match into contact with gunpowder in the priming pan. Usually (but not always) ignited by the shower of sparks or the slow-match, the powder would hopefully not just ‘flash in the pan’ but would in turn ignite the main change of gunpowder in the breech. This then burned – slowly compared to modern propellants – and finally began to drive the ball down the barrel. The target or the weapon muzzle could have moved quite a lot in this period, and to make things even harder, the delay from trigger pull to the ball departing the muzzle was not always predictable.

Smoothbore Weapons

Most early firearms such as muskets were muzzle-loaded smoothbores, i.e. they had no rifling to spin the projectile. Firing a spherical ball that was somewhat smaller than the weapon’s bore, they were anything but accurate. Muskets were loaded by pouring loose gunpowder down the barrel, then dropping the ball on top. Both were held in place by a paper wad, which was pushed into place using a ramrod.

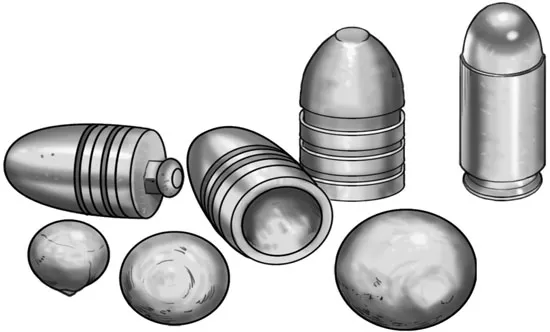

Smoothbore Balls and Minie Bullets

The hollow base of the Minie bullet expands under the gas pressure of firing to fill the whole barrel and grip the rifling. By contrast, a round ball allows some gas to escape around it and rattles around in the bore, reducing both muzzle velocity and accuracy.

Minie Bullet

The Minie bullet had a conical shape with a hollow base and was slightly smaller than the weapon’s bore. When fired, propellant gas pushing the bullet from behind also caused it to expand and grip the rifling. This was an important innovation, as it enabled the creation of fast-firing, rifled, muzzle-loading weapons, which became known ...