![]()

1 Directions to a Serendipitous Encounter

Before you can listen to Refazenda you have to find it. There’s always Discogs, iTunes, Amazon, and eBay, but for the project at hand, a more circuitous route is in order.

Go to Tokyo. Find the record store El Sur. It might take you a while to locate the building, which is in Shibuya, one of Tokyo’s commercial centers. The address you’ll be looking for is 1-15-9 Jinnan. Once you’re there, go inside and take the tiny elevator to the tenth floor. Exit right and then turn left down the hall until you’ve arrived at door 1006.

By now it will be slightly past 3:00 p.m. The sign on the door says (in English) “Open around 2:00-10:00,” but when you knock no one answers. Eventually, a man opens the door, plumes of smoke trailing behind him. He is disheveled and asks you to wait a few minutes longer.

When he returns, he beckons you inside, where you notice a full ashtray and large stash of liquor on the counter next to the cash register. You are also surrounded by an impressive collection of Latin American music.

After browsing for a while, you ask if there are any Gilberto Gil records. There are, and Refazenda is among them. It’s the same album that you purchased in a small CD store in Santiago, Chile some twenty years earlier, before you even knew who Gil was. But unlike that CD, and unlike other versions of the album, this one has liner notes printed directly on the back cover. They’re in Japanese, written by the renowned critic and producer Tōyō Nakamura (中村東洋) in 1979, four years after the album was first released in Brazil.

Buy the album, take it home, and put it on the turntable.

![]()

2 Race and Radical Serendipity

The record you are now listening to, Gilberto Gil’s 1975 Refazenda, is a magical, genre-defying album created by an artist with extraordinary creative breadth and depth. The word “refazenda” is itself a Gilberto Gil-ism: a sonically wrapped linguistic riff meant, depending on one’s perspective, to fight the power or simply in jest. In Portuguese, fazenda means “farm,” but what exactly does re-fazenda mean? Charles Perrone, an expert interpreter of Brazilian music, translates Gil’s invention as: “a neologism that blends the idea of a new farm or plantation (fazenda) with a sense of active renovation based on the Latin form of the gerund; the title may be adequately rendered as ‘refarmulating’. The idea of artistic renewal of self is central to this collection of songs.”1

Newness. Renewal. Farms and the land on which they sit. All course through the album, though not always along the most obvious or visible paths.

And yet there is more. “Farm” is a somewhat neutral term; “fazenda” can also mean “plantation” and carry much weightier meanings. In Brazil, which received more slaves from Africa than any other country in the western hemisphere, and which in 1888 became the last country to abolish slavery, plantations evoke histories of searing pain and brutal violence. In Gil’s hands, then, fazenda holds multiple meanings. This is true not only because “plantation” recalls the horrors of slavery, but also because even “farm” can signify more than one thing. In this case it refers not only to a generic pastoral setting, but specifically to the plots of land that struggle on a yearly basis to produce vegetation in the dry lands of the rural northeast, where Gil spent part of his childhood. Drought and scarcity shape the lives of those who toiled on northeastern fazendas. Thus, a single word calls attention to Brazil’s violent history of human bondage as well as the historical exploitation of poor rural folk. Harnessed to the prefix re-, fazenda takes on further meaning still. At several moments on the album’s title track, for example, Gil replaces “refazenda” with the word refazendo, which means “remaking,” “rebuilding,” or “redoing,” concepts that undergird the entire album and that slide easily into another central idea of the record: “restoring.” Refazenda, in sum, is meant to conjure complex and often painful histories and contemporary realities, while also suggesting paths toward remaking them. That project resulted in not one but three discs, Gil’s famous “re-” trilogy: Refazenda (1975), Refavela (1977), and Realce (1979).

The catch is that searching too hard for meaning can lead to disappointment. It’s not that Refazenda isn’t a universe of meaning, and rather that its brilliantly eclectic sounds, stories, and pathways can make it difficult, if not impossible, to line up personal desires and expectations with the music, the lyrics, and Gil’s often elusive intentions. Some listeners, for example, interpret the opening lines of the title track—“Avocado tree/We will accept your act”—as a barb against the military dictatorship that ruled Brazil from 1964–1985 and the infamous Institutional Acts it used to strengthen its hold on power and persecute opponents. Gil himself swatted away that idea, which, he said years later, “never even crossed my mind.” The song, he explained, was nothing more than “a juxtaposition of nonsenses.”2

Was Gil being coy? It is hard to know for sure; throughout his career he has regularly both exceeded and confounded expectations. This was true in 2015, when he visited the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where I teach. In preparation for the visit, Christopher Dunn, another great interpreter of Gil and the larger Trópicalia musical movement that Gil helped create in the late 1960s, participated in a reading and listening workshop. During the Q&A, the audience—mainly North American scholars unfamiliar with Brazil and its music—seemed simultaneously befuddled and inspired. Surely this black man who had been persecuted and exiled during the dictatorship, who sported an Afro on the cover of Refazenda, and who wore his hair in braids decades later as Minister of Culture for the Worker’s Party (PT), must embody the kind of radical racial and political projects that would be recognizable to the scholars, many of them veterans of the 1960s and steeped in the histories of Marxism, activism, and protest. And yet, Gil so rarely plays the part that audiences and critics expect or want to hear.

The day after the workshop, Gil performed solo with an acoustic guitar for a packed house. For nearly an hour and a half, he held forth on 500 years of Brazilian history, narrated in British- and Brazilian-inflected English and illustrated with six classic songs. As if willed by telepathy, one of the songs that Gil plucked from a repertoire that numbers in the hundreds was “Domingo no parque” (Sunday in the Park). Just a day earlier, Dunn had shown grainy YouTube footage of a famous 1967 performance of the song, which I, in turn, played for my undergraduate students hours before Gil’s performance. Now, here we all were, granted the extraordinary, surprise gift of hearing him play the same song live, a half century later.

For all its majestic qualities, Gil’s lecture-performance that day in Illinois mystified a number of those in attendance. It was rumored that fans across the Midwest had chartered buses when they learned that he would be playing for free. But if some imagined that they would be witness to a tour-style performance, the relatively staid display seemed to disappoint. While the half-dozen songs he played were all greeted with enthusiastic approval, Gil spent long stretches between each number speaking about Brazilian history. His narrative began when Portuguese colonizers and Native Brazilians came together for a “party” on the beach, and then proceeded through an equally improbable succession of harmonious racial encounters. That narrative is familiar in Brazil and is the very same one that on other occasions and in other settings Gil has forcefully challenged and critiqued. The notion that Brazilian slavery was less brutal than the forms that took root elsewhere in the Americas, and that its relatively innocuous manifestation gave rise to a society free of race-based antagonism is known as “racial democracy.” Though activists and scholars have long since proven it to be a myth, the idea lives on, and was recently celebrated by President Jair Bolsonaro, who took office in 2019 and soon after proclaimed, counter to all evidence, that racial prejudice and strife do not exist in Brazil.

Though Gil has often criticized the rhetoric of racial democracy, on stage in Illinois he was m

ore embracing of it, an indication of the varied, changing stances and identities he has taken throughout his life and career. In 1970, when Gil was living in exile, chased from Brazil by the military and settled in London, Brazil’s Museum of Image and Sound (MIS) awarded him its prestigious “Golfinho de Ouro” (Golden Dolphin) prize for his song “Aquele abraço” (That Embrace). Gil not only rejected the award but renounced its premise, which he saw as exemplary of endemic racism in Brazil:

Let it be clear . . . that “Aquele abraço” doesn’t mean . . . that I’ve become a “good negro samba player,” which they want from all blacks who really “know their place.” I don’t know what my place is and I’m nowhere at all; I’m not serving the table of the white masters anymore and I’m no longer sad in Brazil, which they are transforming into the slave quarters.3

It would be hard to think of two more oppositional presentations, but Gil’s 1970 takedown of Brazilian racism and his presentation in Illinois are best understood not as anomalies and instead as two points on a fluid, changing scale of thought and expression.

The changing and sometimes unexpected nature of Gil’s thoughts and expressions—and his penchant for defying expectations—suggests the inadequacy of most labels and categories that have been applied to him and his music. He is most closely associated with Tropicália, a psychedelic amalgamation of genres and sounds that he helped turn into a counterculture phenomenon in the late 1960s. But he has also played (and often helped transform) a seemingly endless number of genres, among them pop, bossa nova, rock, samba, and forró. Gil and his music are also often pigeon-holed racially. But as we will see, always-problematic labels like “black music” are especially inadequate for discussing his multidimensional and sometimes mercurial work and identity.

His life and career, the rapturous performance of “Domingo no parque” in Illinois and the star-crossed hopes of those at the workshop and in the audience for the performance speak to the unique collision of inspiration and expectation that I have come to call Gil’s radical serendipity. The phrase is meant to define Gil’s critics and interpreters as much as his own work and ideas. Look hard enough at his life, listen closely enough to his music, and you are as likely to discover something revolutionary as you are to find yourself floating in a delicious stew of “nonsense” that can be disorienting, confounding, enlightening, or all of these things at once.

This complex reality may be, at least in part, a product of some of the paradoxes and challenges that have shaped Gil’s Brazil, a nation built on slavery that still managed to spin a tale of historic racial harmony. During the military dictatorship, Gil faced criticism for Refavela (1977), a follow-up to Refazenda that highlighted Brazil’s impoverished favelas (makeshift hillside communities). The press responded negatively to Refavela, Gil explained, because they felt he was not expressing the appropriate kind of blackness. Brazilian racial categories are famously numerous and pliable. During the 1970s, some activists in Brazil embraced the English word black in favor of the Portuguese negro, a term commonly used to refer to people of African descent. The word negro can translate as “black,” but during the 1960s and 1970s could also mean something closer to the English negro. For some in the Brazilian Black Power movement, the foreign word black was desirable because it shed some of the weighty history attached to negro, while also providing a link to struggles for racial justice and equality elsewhere. The move did not sit well with many of Brazil’s opinion makers, and Gil was caught in the crosshairs. The press, he said, reacted unfavorably to Refavela “because the attitude of the album was black and at the time most journalists were against black, not against negro, but against black, the consciousness that is connected to the international sphere and isn’t just Brazilian.”4

In other words, Gil was dealing with a world that would accept and even celebrate or demand one form of blackness while rejecting another.

![]()

3 Cover to Cover (and an Invitation)

Though Refazenda does not display the exact same racial “attitude” as Refavela, it emits other, no less meaningful, statements and provocations. Gil created Refazenda and Refavela (and Realce) amid a repressive atmosphere that inspired independent-minded artists to “dribble around the censor” (driblar a censura), a Brazilian phrase for finding creative ways to avoid punishment with artistry akin to Brazilian soccer stars.

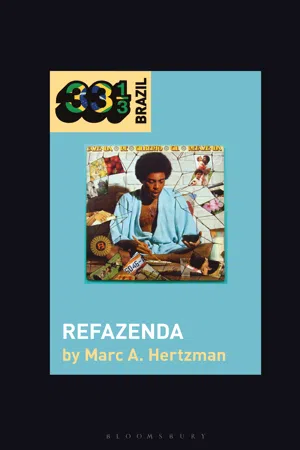

Gil’s ability to navigate complex, paradoxical terrains and his wondrous ability to turn “nonsense” into something transformative is evident in Refazenda’s front cover, whose very inscrutability grabbed me and wouldn’t let go the first time I held it in my hands. There Gil sits, cross-legged, blue robe draped around his shoulders and open to the navel, chopsticks in one hand and a bowl in the other, poised to consume what some have surmised to be a dish from the macrobiotic regimen that he has famously followed (if not without exceptions) for years. The food and eating implements also conjure enduring metaphors of Brazilian culture. During the 1920s a group of modernist writers and authors flipped colonial stereotypes about Brazilian savagery and cannibalism on their head, embracing a fig...