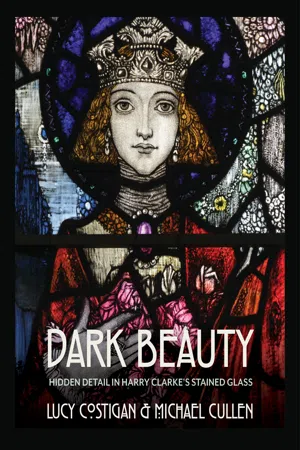

![]()

1

MASTER OF COLOUR AND LIGHT

Harry Clarke’s contribution to the development of stained glass in Ireland was immense. To put his achievement into context, his work is consistently ranked among the international masters, such as Tiffany, Burne-Jones and the medieval colourists. His legacy is all the more remarkable when we consider the abysmal state of stained glass that prevailed in Ireland when he was born in the late nineteenth century. Mass-produced panels of poor quality were imported from Europe,1 most notably from Munich, Birmingham or London and assembled in Ireland.2 An article in The Irish Builder3 complained about ‘abominably vulgar foreign windows so common in Ireland’. As part of the resurgence of art and literature in Ireland, several artists began working in the medium of stained glass to improve its standard. Sarah Purser founded An Túr Gloine (The Tower of Glass) studio in 1903. Christopher Whall, British Arts and Crafts stained-glass artist, was adviser to the studio. Alfred E. Child, stained-glass artist and teacher at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art, managed the studios. Harry Clarke was to become the supreme master of colour, composition, design and originality in this flowering of excellence that included fine artists such as Beatrice Elvery, Catherine O’Brien, Wilhelmina Geddes, Michael Healy and Ethel Rhind.4

In a recent publication, Clarke’s style was contrasted with the nineteenth-century Munich style of stained glass, to give an illuminating insight into his originality and creative brilliance:5

Munich Style painters strove to even out the light passing through the glass by applying a matte of glass paint over the entire window which, while still retaining fabulous colour, tended to ‘flatten’ the visual effect. As a result, Munich Style windows tend to glow rather than sparkle … In stark contrast, the Irish style of glass painting, pioneered by Harry Clarke in Dublin in the 1920s, will shimmer and dance before the eyes of the viewer in a most delightful and exciting manner. This is achieved by retaining areas of unpainted antique glass and contrasting them with heavy black diapering to create a dynamic vibrancy of light and colour.

Clarke’s contemporaries, his influential friends, patrons and critics constantly championed his work. Thomas Bodkin, first director of the National Gallery of Ireland, described Clarke in an article that extolled the merits of his newly-exhibited windows that were bound for Glasgow and Terenure:6 ‘Mr. Harry Clarke excels himself. Such is his pleasant custom. He never recedes: he never stands still. With each fresh work he shows a power that grows steadily deeper and stronger. “Genius” is the only word in my vocabulary which does full justice to the measure of his gifts as an artist in stained and painted glass.’

In the medium of book illustration, his work also won critical acclaim. In his memoirs, Clarke’s publisher, George Harrap, described his bafflement that other publishers had failed to recognise Clarke’s rare artistic talents:7 ‘Why did not the very first publisher take this Irish genius to his heart? ... He came into my room late in the afternoon, slim, pale and youthful, with the air of one who has had rebuffs. He opened his portfolio very shyly, and with delicate fingers drew out his lovely drawings.’

Clarke’s originality, while delighting his admirers, also incensed the more traditional and conservative viewers of his work. Some critics, members of the clergy and ultimately the Irish government criticised his overtly sexualised and erotic figures8 in book illustrations and secular work; the contemporary faces and dress he sometimes used in windows that depicted Our Lady and saints in religious work; his portrayal of Irish characters as bawdy and decadent and his depiction of literary works that had been banned and disparaged by Church and State in The Geneva Window (1930).9

Harry Clarke, c. 1925, courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

Politically, Ireland in the 1920s was coming to terms with revolution, partition, the end of colonial rule, a world war and a civil war. After so much upheaval, Ireland battened down the hatches, becoming one of the most conservative countries in Europe, where the Catholic Church greatly influenced the government’s policies and imposed a strict moral code on its people. It was far from an ideal place for artists and writers to freely create, experiment and openly challenge. Although Clarke had never been overly political, he became entangled in forces that he could not control. In this context, his work is all the more fascinating to behold, in its daring and bravery. We might well ask: how did he ever get away with it, weaving those dark and grotesque figures into his religious and secular windows in such an unenlightened age?

BEGINNINGS

Born on St Patrick’s Day in 1889, Henry Patrick (Harry) Clarke grew up with a stained-glass studio at the back of his home, at 33 North Frederick Street, Dublin. His father, Joshua, had emigrated from Leeds to Dublin at the age of eighteen and had set up a church decorating business in 1886.10 Joshua was forced to commission designs for stained glass from English artists, such was the lack of skill in Ireland.11 He married Brigid McGonigal, originally from Cliffony, Co. Sligo.12 The couple had four children, Walter, Kathleen (Lally), Florence (Dolly) and Harry. Joshua changed the business name to J. Clarke and Sons in 1892, after the birth of his two sons.13 Brigid suffered from poor health for most of her life.14 She died in 1903 at the age of forty-three, when Clarke was just fourteen years old. This greatly affected him as he had been very close to his mother.15 Both Harry and his brother, Walter, inherited the tendency towards ill health, particularly chest complaints.16

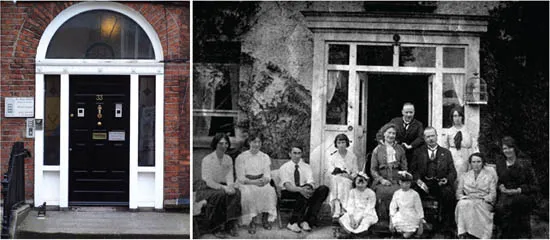

From left:

33 North Frederick Street, Dublin 1, Lucy Costigan.

The Clarke Family. Standing: Walter; sitting from left to right: Minnie, Margaret, Harry, Kathleen, Ethel Rhind, Joshua, Dolly, rest unknown, c. 1917–18, at Cluain na Greine, Shankill, Co. Dublin, courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

Even as a young child, Clarke showed an aptitude for drawing and design. He attended Marlborough Model Scho...