![]()

1

Introduction

Molotov cocktails and terrorism in the Basque Country

After a street demonstration in 1992 in the city of Bilbao, Yulen and his brother threw a Molotov cocktail into the offices of Spain’s national train company. It was a time of widespread “kale borroka” in the Basque Country, the territory claimed as homeland by the Basque people who straddle modern state borders in the north of Spain and southwest of France. This Basque-language term, which translates roughly to “street struggle,” was widely used in Spain to refer to actions in which Basque youth aired their political frustrations in the streets by destroying cash machines, throwing stones at party offices or smashing the windows of agencies for temporary employment. In explaining their decision to throw the Molotov cocktail, Yulen cited the brothers’ anger at the disproportionate use of force by police earlier that day against participants in a public demonstration by the Basque left-nationalist movement, a group in favor of an independent and socialist Basque Country (Interview S-23).

At the time when the brothers threw the Molotov cocktail, instances of property destruction in the context of kale borroka were usually brought before local courts as cases of public disorder, generally leading to fines for misdemeanors or short jail sentences (Annual Report of the Attorney General Spain or Memoria Anual [MA] 1993:416). Indictments in these instances usually focused on the economic damage inflicted through kale borroka protest actions (MA 1993:147). Yulen and his brother, however, met with a different legal response. Investigative judges from the Audiencia Nacional (National Court) in Madrid stepped in and claimed jurisdiction over the brothers’ case. This specialized court for certain types of serious crimes, such as terrorism and money laundering, sentenced the two brothers to ten years in prison each – while not being members of ETA – for having “collaborated with the goals and objectives of ETA,” the notorious underground organization Euskadi Ta Askatasuna that has advocated using armed struggle to achieve an independent Basque Country and killed numerous officers of the Guardia Civil (Spain’s national military police force) and later also politicians and journalists to further this aim.

The brothers’ case set a new precedent, kicking off a battle between defense lawyers and prosecutors over the jurisdiction of the Audiencia Nacional in incidents related to kale borroka. Key to their success in obtaining jurisdiction, the Madrid prosecutors did not describe the brothers’ acts of vandalism as separate and isolated events. Instead, they labeled participants in kale borroka as “groups of support to ETA” in order to categorize their actions as a terrorist offense (for example, MA 1994:156). This trend continued and by the end of the 1990s, it had become routine to qualify acts of kale borroka as terrorism, with such cases automatically going to the Audiencia Nacional. A new law in 2000 (LO 7/2000) cemented this development by turning “material destruction” into a terrorist crime, even if the perpetrator did not belong to an armed organization, as long as it was done with the goal to “subvert the constitution” or “change the public peace.”

Since the Audiencia Nacional’s founding in 1977, the court has tried ETA militants for carrying out or collaborating in armed attacks. Even though kale borroka actions had always been viewed as springing from the general milieu around ETA, they were not prosecuted as terrorism before the 1992 case. The move to bring these cases to the Audiencia Nacional fitted with a prosecutorial theory that claimed – based on ideas attributed to ETA leader “Txelis” – that ETA needed constant low-level sabotage during the times when its commandos were not active to keep up pressure on selected targets (for example, court houses or political party offices). In the words of an investigative judge at the Audiencia Nacional, kale borroka was thus part of ETA’s strategy to maintain a “permanent coercive effect on citizens” (Case Kale Borroka, 19 October 2007). According to this narrative, ETA actually orchestrated kale borroka, a view that gradually became institutionalized through court decisions. Supporters of the Basque left-nationalist movement, a collective of parties and grassroots organizations and groups whose common denominator is the nationalist and socialist project, criticized the new portrayal of kale borroka by prosecutors. Many left-nationalists denied the existence of ETA-coordinated protest groups and – even though some kale borroka actions were actually claimed in communiqués (Van den Broek 2004:719) – emphasized the often spontaneous participation of frustrated youth in kale borroka.

This book focuses on the key role that “prosecutorial narrative” – the official accusation and explanation of what makes certain conduct a crime delivered in court by a prosecutor tasked with the authority and responsibility of representing the public interest – plays in reproducing and legitimizing certain societal views, while marginalizing others. By choosing to describe conduct in a particular manner in the courtroom, prosecutors can enable changes in the way conduct is defined judicially, with significant impact on criminal prosecution and sentencing. Classifying kale borroka actions as terrorism, for instance, not only results in higher sentences (up to 18 years in prison) than for public disorder, but also opens up the possibility for incommunicado detention and the dispersion of the convicts across Spain. The example of the changed label for kale borroka further shows that prosecutors do not simply apply the law – as if the law is static and straightforward – but rather play a key role in shaping the way events are legally qualified and taken to court. As this book endeavors to demonstrate, this is not only the case with regard to prosecutors in Spain in the special situation of its long-standing struggle against ETA, but is part and parcel of the application of the law in contested socio-political terrain.

The application of law involves, however, what I call “prosecutorial narratives,” which imply the choice of a context, selection and interpretation of the facts, and the choice of certain perpetrators. Defendants, their supporters and their critics all struggle to define this narrative, which not only becomes the key to influencing the initiation, scope and course of criminal proceedings, but also a major truth-producer publicly communicating about political events, grievances and identities. Prosecutorial narratives simultaneously provide the basis for the choices made in specific criminal prosecutions and fulfill the function of legitimizing the very endeavor of dealing with the issue at hand in the criminal justice arena.

Unlike in authoritarian dictatorships, the legal institutions of liberal democracies rest on the assumption of a society in consensus, in the sense that society is expected to be made up of free and equal citizens, and where dissent can be solved in parliament or civil lawsuits. In such a society, the prosecutor is expected to act in the public interest. In reality, as criminal law professor Alan Norrie (1993:222) has pointed out, society is divided and criminal law functions as a mechanism of social control. The existence of social and political conflicts in democratic societies is ignored in the ideology of liberal legalism and crime conceptualized as “the result of individual calculations” (Norrie 1993:58). While prosecutors are expected to act in “the public interest,” Norrie cautions that “The law embodies a logic of individual right to be applied universally, but is in reality applied to one group by another” (Norrie 1993:31).

What do prosecutors do when the public is divided and interest groups advocate for radically different understandings of what is criminal and how to apply the law? In such instances, the prosecutorial narrative becomes the focus of discursive action and mobilization by groups in society claiming victimhood and seeking to define certain conduct as criminal, while those facing criminal charges counter-mobilize to challenge the claims and/or assert the legitimacy of their actions. By comparing episodes of such “contentious criminalization” across three well-established liberal democracies – Spain, Chile and the United States – this book attempts to shed light on what happens when political contestation moves into the criminal justice arena, where the issues, demands and actors become co-determined by the logic and language of criminal law and procedure. Rather than assuming that the criminal justice system and its performance are fixed and natural, this book follows sociologist David Garland (1990:4) in suggesting that it may be challenged and subsequently change.

In Spain, the book traces the shifting and contested prosecutorial narratives about ETA and its alleged support network in the Basque left-nationalist movement, which represents a broader struggle for a free and socialist Basque Country that clashes with the political and territorial unity inscribed in Spain’s Constitution. Established in 1959, the armed organization ETA was originally founded to fight against the Franco dictatorship. In 1973, members of ETA killed General Carrero Blanco, the supposed successor of Franco, garnering significant popular support for the armed Basque organization. Even after Spain’s transition to democracy, however, ETA continued its deadly attacks, justified by what the organization and its sympathizers saw as an undemocratic state of exception in the Basque Country, where the Basque people faced repression and lacked a political path to independence. In 1978, almost half of Spain’s Basque citizens viewed ETA members as idealists or patriots, as compared to just 7 percent who considered them criminals (Alonso and Reinares 2005:267). According to the annual reports of the prosecutor’s office, during this time period the Spanish state viewed ETA as an opponent in a war (MA 1979:65), though this changed over the course of the 1990s, when the criminal justice system became the main venue for encounters between the state, ETA, and its supporters. At the same time, by implementing the Statute of Basque Autonomy, passed on 18 December 1979, significant powers were transferred from Madrid to the regional government of the Basque Country in areas including health care, policing and taxation. In 2010 ETA announced a permanent ceasefire and in 2018 its leaders dissolved the organization.

In Chile, the book explores prosecutions set in the context of the so-called “Mapuche conflict,” in which Mapuche indigenous groups demand the return of lands from which they were dispossessed by the Chilean government in 1883. These lands are now predominantly in the hands of timber companies and large-scale farmers, who argue that their forestry plantations serve the public interest, as they claim they create jobs and benefit the country’s economic growth while also protecting native forests. Mapuche activists, on the other hand, question who the plantations really benefit, emphasizing their historic right to their ancestral lands and highlighting how the industrial plantations create water shortages for adjacent Mapuche communities. In the face of protracted political inertia on the issue of land redistribution, Mapuche activists began to stage occupations of disputed lands, leading to criminal prosecutions against them. In other cases, Mapuche activists have been accused of arson of plantations. The book shows how the present-day landowners successfully mobilized to influence prosecutorial narrative by appealing to law and order in cases of property destruction and portraying themselves as “victims” of a radical minority who sought to leverage their Mapuche identity for personal gain. However, the oscillation in these cases between viewing Mapuche land occupations as criminal conduct to seeing them as a form of legitimate civil disobedience shows how prosecutorial narrative is not neutral, but inevitably reproduces and elevates certain arguments and power relations in society, marginalizing others.

In the US, the book traces the discursive battles surrounding prosecutorial narratives on “eco-terrorism” in the context of animal rights and environmentalist activism against practices like animal testing, fur farms or tree logging. While mainstream conservationist and animal welfare organizations receive widespread support in American society, the more radical ideas of animal rights and nature-centered demands have been viewed with skepticism. In 1979, animal rights activists for the first time broke into a lab in order to release caged animals. In 1980, the radical environmentalist group Earth First! was founded, a group that engaged in tree-sits and came up with wilderness proposals. For a long time, protest actions like the release of animals from fur farms or testing laboratories were not a priority for US law enforcement agencies. In 1998, the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Louis Freeh said that “[e]co- and animal rights terrorism […] was not an issue, not a priority and not on the agency’s ‘radar screen.’” Fur farmers were outraged by the lack of attention to the activist raids they experienced, so they mobilized and lobbied the FBI for more protection. Just seven years later, on 24 August 2005, a top FBI official declared the “eco-terrorism, animal-rights movement” to be “the No. 1 domestic terrorism threat” in the US (Schuster 2005). This threat assessment was accompanied by a proactive approach to investigating activist groups, including the use of FBI informants, conspiracy charges, and a prosecutorial demand for higher sentences as a deterrent to other activists. By 2009, the release of animals in the context of animal rights activism had transformed into a terrorist offense and two activists were convicted and sentenced to 21 and 24 months respectively, under the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act (AETA) for the release of 650 mink from a fur farm in Utah.

My long response to a Chilean prosecutor

The idea for this book emerged while attending a trial against three Mapuche activists in Chile in April 2003. Rather than focus narrowly on the three defendants and the particular criminal actions imputed, the prosecutor’s opening statement traced Chilean–Mapuche relations from the 19th-century war that forced the indigenous group into reservations, ending with an analysis of how the defendants “abused” their indigenous Mapuche identity to get away with arson at a plantation simply because it was on disputed land subject to historical Mapuche claims. The politicization of the trial and evident centrality of criminal justice proceedings within the dynamics of the so-called “Mapuche conflict” in Chile sparked my interest in processes of criminalization in complex situations of protracted socio-political contestation.

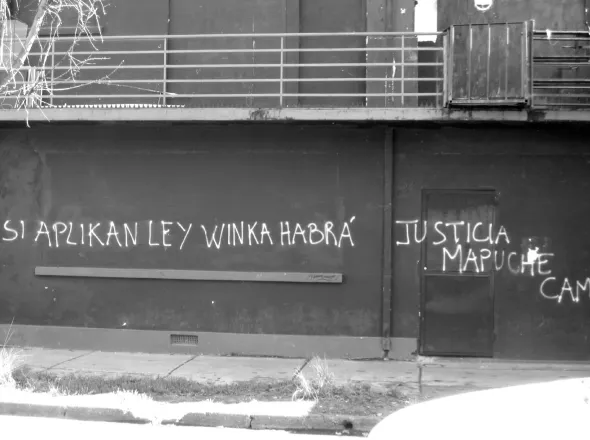

Shortly thereafter, in an interview with Esmirna Vidal, the regional prosecutor for the 9th Region in the south of Chile, she stressed to me that her job was simply “to apply the democratic mandate of the law” (Interview 2003, C-10). Her reference to the law as the basis and final arbiter of her job supposedly closed the discussion about the choices she made and the way she conducted criminal proceedings in an obviously challenging political context. Newspaper headlines at the time speculated about the impending outbreak of a “Mapuche Intifada.” Graffiti in the streets of Temuco threatened the prosecutors that “if they apply winka [Chilean] law, there will be Mapuche justice” (see Photo 1). Clearly, “just applying the law” was more complicated than she made it out to be. Her remark sparked my desire to understand more profoundly the dynamics in and role of prosecutorial offices, and to go beyond the simplicity of her evasive resort to her legal mandate to explain her decisions. This book is, in that sense, a lengthy response to Prosecutor Vidal, in which I argue that “applying the democratic mandate of the law” is the beginning rather than the end of a much larger discussion on the role of prosecutorial narrative in situations of contentious criminalization in liberal democracies.

Photo 1 Picture taken in the streets in the southern city Temuco, Chile, April 2009

Of the prosecutors I interviewed in Spain, Chile and the United States, many acknowledged the different ways in which fitting facts to existing norms is a more complex process than simply “applying the law.” Yet, to maintain their authority and legitimacy as unbiased representatives of the public interest, prosecutors often rely on and reproduce notions of “the law” as an uncontroversial and established body of norms that enjoy societal consensus, enabling them to hide choices they make by insisting that all they do is “apply the law.” This book is about the fuzzy frontier that prosecutors negotiate as they attempt to remain neutral and avoid politics, but also take into account the context in which crimes occur. In liberal democracies, people are supposed to be prosecuted for what they do rather than who they are or what they stand for. Echoing these precepts, the spokesperson of a regiona...