![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Human society has to work to survive.1 Our food, clothing, and shelter are won by work and, as every parent knows, the next generation is raised by work. Society is, before all else, a collective effort to ensure its own physical continuity.

We are all born into and formed by a society already structured around collective tasks of physical production, of human reproduction, and the reproduction of the social relations that achieve it all.

Societies distribute their members into different social roles, and divide up their waking hours between activities. Some activities, like feeding or dressing oneself, are purely personal. Some, like childcare, family cooking, farming, or industry, benefit others. Different kinds of activity produce their own useful effects: sex—babies, baking—bread, bricklaying—walls. For each effect we need to carry out particular sequences of body movements that interact with the environment, implements, and other people. These are the concrete aspects of activity.

But from the standpoint of society as a whole, each activity has another more abstract aspect, since each is part of the division of labor. The bodies and time of its members are society’s fundamental resource. They are both limited. There are only a given number of people alive on any given day, and there are only 24 hours in the day, for some of which our bodies must sleep. The social division of labor has to partition the available time of all these bodies between the tasks required for survival. What is being divided up here are all the millions of person hours that go to make up the social working day. This is the abstract social aspect of activity: activity as part of the social organism.

The division of labor combines a concrete achieved result, particular bodies performing specific actions, with the abstract possibility of a different result. The allocation of bodies to tasks would have to be different. You or I could be doing a different job in six months’ time. Had circumstances been other, we could have been doing something different right now.

For a division of labor to exist bodies must be flexible, able to perform more than one task. We can do this. We can switch, we can learn.

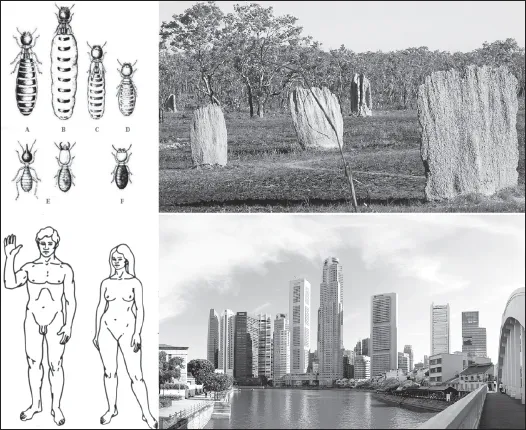

We humans are neither the only, nor the first social animals on Earth. Before our towns, there were the castles of the termites, the apartment blocks of the bees, and mazes of the mole rats. Termites are, in terms of sheer biomass and food consumption, the dominant social organism. Our biomass totals some 350 million tons [Walpole et al., 2012], that of termites, 450 million tons [Sanderson, 1996].

These societies too have their division of labor. Termite workers build towers every bit as tall in relation to their bodies as our skyscrapers. They gather wood, they tend underground mushroom gardens and look after young ones. This is a fluctuating division of labor. The proportions of workers performing different tasks vary according to the needs of the colony.

They have a limited repertoire of tasks and their technology changes only over evolutionary time scales, but this is still a division of labor. Individual termite workers do not learn. As species they learn, but any technology they use, and once, millions of years ago, each of their technologies must have been new, was acquired by the slow process of genetic adaptation.

Alongside the workers, their mounds contain others. They are polymorphic species.

There are soldier termites with huge heads and mandibles, huge mothers, and medium-sized fathers. The soldiers cannot work. Their sole task is to defend the home from ants. They block the passages with their huge heads, biting intruders, or squirting noxious glue at them. Aside from this, they are unproductive, unable to gather wood or raise crops, dependent on the workers for their food.

The huge mother or “queen,” a sort of yellowish pulsating striped sausage as big as a man’s finger, can’t work either. She lies in her secure chamber, panting, being fed fungus as she lays eggs. The activities of the mother and the soldiers are always concrete: the mother lays eggs, the soldiers defend. They cannot take up tasks as the need arises the way the workers do.

Faced with insect societies people find it hard not to make analogies to our own. The terms worker, soldier, queen are obvious analogies: a projection of the class systems of our society onto a very alien one. People use the term castes to describe the different termite body forms, an obvious analogy with the ancient social system of India. But this analogy is limited. The bodies of people in different Indian castes are the same, it is social pressure, not physique, that forces people into the types of work associated with castes. Indian castes, moreover, are hereditary, whereas the members of different “castes” in a termite nest, workers or soldiers all share the same parents.

Figure 1.1. Termites are, in biomass, the dominant social organism on Earth. Their workers build towers every bit as tall in relation to their bodies as our skyscrapers. They are polymorphic animals with multiple different body forms within a colony. A: Primary king, B: Primary queen, C: Secondary queen, D: Tertiary queen, E: Soldiers, F: Worker. Because of this polymorphism they do not have a fully developed division of labor. The other main social animal on Earth is dimorphic and can have a more general division of labor. Source: NASA and Wikimedia.

The point that is validly made when talking of termite castes though, is that like the castes of the Hindus; the different body forms of the termites impede a flexible division of labor [Ambedkar, 1982].

Although termite soldiers cannot transfer to building work or vice-versa, there has to be some mechanism regulating the proportions of these two body forms. Too few soldiers in an environment with a lot of hostile ants could be fatal for the colony, but too many means a lot of idle mouths for the workers to feed. In principle the caste ratios could be regulated genetically with different queens laying eggs whose soldier ratio varied. There is some evidence that this is the case [Long et al., 2003]. Here, although a given termite society could not fully regulate its division of labor, natural selection would mean that over a series of generations of colonies, the soldier ratio would adapt to the average needs of these colonies.

Another possibility is that pheromones are used to adjust the development of individuals into different body forms as the need arises [Long et al., 2003]. If this is the mechanism, then even though a mature termite cannot change caste, the caste into which a young one matures is decided quite late in life, so that the colony can adjust the composition of its workforce quite rapidly. This would imply that there was actually more occupational mobility among the termites than in human caste societies.

Why pay attention to these odd little creatures with their grotesquely differentiated bodies?

Because it is easier to recognize features of the familiar when contemplating the strange.

The termites and other social insects seem perfect examples of communism. The individuals act primarily in the interests of the community as a whole rather than themselves. Termite soldiers willingly sacrifice their lives for the sake of their colony. If there is a hole formed in the nest, the soldiers rush out to confront any ants that attempt to break in, while behind them the workers wall up the hole. There is no retreat for them. When the workers finish the wall, the soldiers are marooned outside. Worker bees will fearlessly mob hornets. Many die from the hornet’s sting, but by surrounding the hornet and buzzing they cause it to die of heat exhaustion.

The superiority of this communist lifestyle is testified by the ecologically dominant position that the social insects, particularly the termites and ants, occupy. Anyone who has seen these creatures cannot but be impressed by the complete domination that an army of carnivorous African driver ants exerts over the territory it marches through, the fearful network of miniature tracks, trunk, and major roads with multilane traffic and the panic of other insects in the locality. and their fruitless attempts to escape before being torn limb from limb by tiny tormentors who form up into teams to pull a beetle or cockroach apart. Their distant relatives, the peaceful termites, exert a hidden, more subtle but even greater domination, venturing out only in their temporary vaulted paths. Secure from predation behind these walls they gather so much dead wood for their mushroom caves that they dominate their ecosystems. No land animal, other than our domestic cattle, has more biomass.

The literally fraternal solidarity of social insects arises because they are all members of the same family with the same parents. When a soldier termite sacrifices itself, it is protecting its direct kin, and indirectly maximizing the survival of its own genes. But look at it another way and we see in these communities the very image of monarchical despotism and exploitation, with workers perpetually on the verge of rebellion.

Think of the poor worker bees. Genetically female but deprived of the power to bear their own offspring, they toil all their lives for a queen who alone is allowed to lay eggs. They are kept in this subordination by the pheromones released by the queen. Take these pheromones away and they rebel. Nieh [2012] writes that:

After their queen has left with a swarm, orphaned larvae exhibiting rebel traits emerge in honeybee colonies. As adults, these orphans have reduced food glands to feed the colony’s larvae and more developed ovaries to selfishly reproduce their own offspring.

Until exo-planets were discovered we had imagined that all planetary systems would be like ours. Now, with a knowledge of their vast diversity, the masked peculiarity of the solar system becomes apparent, and hence a problem for science.

Contemporary academic economics eternalizes the institutions not just of human society, but of contemporary Western capitalism.2 Anthropologists, archaeologists, and biologists studying social organisms all bring home to us the variety of forms that the production and reproduction of social life can have. They help us to question features that economics takes for granted.

Termite polymorphism (fig. 1.1) might seem irrelevant unless it reminds that we are no more monomorphic than them. We are dimorphic, with male and female body forms. Externally the differences between human females and males do not strike us as grotesque, the way those between termite queens and termite workers do. But in reality we are acutely aware of these slighter differences that impinge profoundly on our social division of labor.3

All termite castes are to some degree disabled: only soldiers can defend themselves, only alates4 can fly, only queens lay eggs, only workers build. Their forms mean that among them the abstract potential of the division of labor is only realized between generations. But this is not true of humans: half have bodies that allow full participation in all social tasks. Women have a flexibility no termite has. They can do any human work.5 But unlike insects we each learn our tasks within one lifetime. The great development of human technology owes itself both to this ability to learn and to the ability to transmit learned skills between generations.

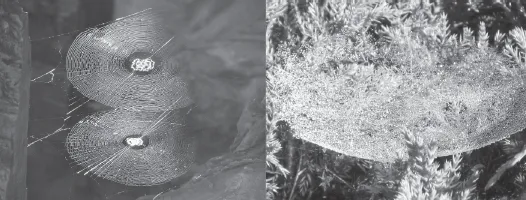

There is technological evolution by other animals. Spider webs are a technology that has developed from orb webs, which seem to be the primitive form, to sheet webs or cobwebs (fig. 1.2). The oldest orb webs known from fossils date from the Cretaceous, but we have fossils of the orb web spiders themselves dating from the Jurassic. There appear to have been several subsequent independent inventions of the sheet web since then [Blackledge et al., 2009]. Dimitrov et al. [2012] argue that sheet webs do not have to obey the same strict architectural constraints that govern orb webs. This allows spiders to use spaces where orbs cannot be constructed or are very inefficient in catching prey. This is an example of technological development, but one that took tens of millions of years to achieve. Knowledge of how to build a new type of web can only be passed on from a mother spider to her offspring if it is encoded in her genes, and it has been acquired by natural selection.6 But when women started to develop weaving and textile technology—perhaps around 7000 BC [Barber, 1991] they were able to pass on improvements to their daughters by word and example leading to a rapid development of forms and types of cloth: linen, woolen, different weaves and knits.

Figure 1.2. Technological development by animals. The primitive orb web (left) was developed into the sheet web (right) which can be placed in positions that are unusable by orb webs. Source: Wikimedia.

This kind of transmission of cultural information is not unique to us. It has been known since Darwin’s day that other primates can use tools.7 Since Goodall’s studies at Gombe we have known that tool use can be a local culture [Whiten et al., 1999] rather than a universal trait. The ability to form distinct technical cultures is a primitive primate trait, just more developed among humans. Our greater ability in this stems from our being able to use language rather than mere example to educate our infants.

Our dynamic development of technology has allowed our species to completely transform the way it lives. This is not just a matter of changes in the way we obtain our food: going from hunting to herding, from gathering wild plants to raising crops. It is also a matter of changing divisions of labor, changing the social relations that organize labor, and the growth of ever more complex relations of domination, subordination, and rebellion.

We will be looking at the way technologies have structured the allocation of human time, the social relations under which this has been regulated, and the forms of exploitation and struggles for freedom that this has given rise to. We will deal relatively briefly with the period before the Industrial Revolution, but look at social relations in increasing detail as we explain the dominant structures of today’s world economy.

The precondition of any society is the reproduction of people. This is the most basic, in the sense of fundamental, branch of the division of labor. But it is something that in contemporary society appears as not part of the economy. Instead it appears as just “family life,” something that is private rather than social. Capitalist market society does not think of an activity as economic unless it involves money. But activities done for payment have been only a very small part of economic life until recently. Even now, they constitute barely half of economic life. If we cast aside the historically narrow perspective that only paid work is work, it becomes clear that sex and the bearing, feeding, and socialization of children are the foundation of economic life.

It is trivially true that without people there would be no economy, but in asserting that human reproduction is the foundation of the economy we are saying more than this.

• The production of the next generation takes time and bodily effort, and the availability of time and energy are the fundamental constraints that any economy has to obey.

• Reproduction determines population. Population changes can drive economic change and changes in power relations. This applies as much today as it ever did.

• The perspective that orthodox economics has is individualist. It defines the “economic problem” in terms of individuals maximizsing their satisfaction. When we take reproduction as our starting point we focus instead on society as an organism. This organism has to reproduce its own conditions of existence: the people, the resources they use, and the social relations they live in. The matter ...