![]()

Part 1

Putting financial strategy into context

1 Corporate financial strategy: setting the context

2 What does the share price tell us?

3 Executive summary: linking corporate and financial strategies

4 Linking corporate and financial strategies

5 Financial strategies over the life cycle

6 Corporate governance and financial strategy

![]()

1 Corporate financial strategy

Setting the context

Learning objectives

Introduction

Financial strategy and standard financial theory

Risk and return: a fundamental of finance

Financial strategy

Valuing investments

Creating shareholder value

Sustainable competitive advantage

Managing and measuring shareholder value

Shareholder Value Added

Economic profit

Total shareholder return

Some reflections on shareholder value

Reasons that market value might differ from fundamental value

Who are the shareholders?

Other stakeholders

Agency theory

The importance of accounting results

Behavioural finance

Key messages

Suggested further reading

Learning objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

1 Understand what financial strategy is, and how it can add value.

2 Explain why shareholder value is created by investments with a positive net present value.

3 Appreciate how the relationship between perceived risk and required return governs companies and investors.

4 Differentiate the different models of measuring shareholder value.

5 Explain why share price is not necessarily a good proxy for company value.

6 Outline how agency theory is relevant to corporate finance.

7 Identify the impact of different stakeholders on financial strategy and shareholder value.

Introduction

The main focus of a financial strategy is on the financial aspects of strategic decisions. Inevitably, this implies a close linkage with the interests of shareholders and hence with capital markets. However, a sound financial strategy must, like the best corporate and competitive strategies, take account of all the external and internal stakeholders in the business.

Capital market theories and research are mainly concerned with the macro economic level, whereas financial strategies are specific and tailored to the needs of the individual company and, in some cases, even to subdivisions within that company. Therefore the working definition of financial strategy which will be used throughout the book tries to take account of the need to focus on these interrelationships at the micro level of individual business organizations.

Financial strategy has two components:

(1) Raising the funds needed by an organization in the most appropriate manner.

(2) Managing the employment of those funds within the organization.

When we discuss the most appropriate manner for raising funds, we take account both of the overall strategy of the organization and the combined weighted requirements of its key stakeholders. It is important to realize that ‘most appropriate’ might not mean ‘at the lowest cost’: a major objective of financial strategy should be to add value, which may not always be achieved by attempting to minimize costs. And when we discuss the employment of funds, we include within that the decision to reinvest or distribute any profit generated by the organization.

A major objective for commercial organizations is to develop a sustainable competitive advantage in order to achieve a more than acceptable, risk adjusted rate of return for the key stakeholders. Therefore, a logical way to judge the success of a financial strategy is by reference to the contribution made to such an overall objective.

Financial strategy and standard financial theory

Let us state our case immediately – if you worship at the altar of the efficient market hypothesis; if you consider that the market value of a company really reflects the discounted value of its future cash flows; if you believe implicitly the work of Modigliani and Miller (as an absolute rather than as a guide to theory development), then some of what you read in this book is going to make you uncomfortable.1

However, if you have ever wondered why it is that intelligent and well-qualified finance directors and their advisers seem to be prepared to spend large amounts of their time and their shareholders’ money devising complex schemes to do things which, according to financial theory, are either completely unproductive or actually counterproductive in terms of increasing shareholder wealth … read on.

There is a large body of research evidence which indicates that financial markets are quite efficient at identifying and allowing for some relatively simple accounting tricks, such as changes in inventory valuation or depreciation policies. The research shows that such accounting manoeuvres do not increase company value, as the markets see through them. However, as will be illustrated by the real examples used throughout the book, many reputable companies employ sophisticated ‘creative’ accounting presentations to disguise the effects of their (presumably widely understood) transactions. A major thrust of this book is therefore to try to bridge this gap between the academic theorists, who profess to believe that financial markets are becoming ever more efficient and perfect, and the practising financial managers, who ignore the financial theory and rely on what they see as working in practice.

A fundamental proposition behind this book is that financial theory fulfils a very useful conceptual role in providing an analytical framework with which to dissect and understand actual, individual corporate finance transactions. It is also a major contention of ours that people are wrong to interpret financial theory as suggesting that shareholder value cannot be significantly improved by the implementation of the most appropriate financial strategy for each particular business. Value, as we shall see, is a function of the relationship between perceived risk and required return. Shareholders, and other key stakeholders, do not all perceive risks in the same way, nor do they have the same desired relationship between risk and return. Thus value can be created in the cracks between the different perceptions, and it is here that financial strategy can blossom.

Risk and return: a fundamental of finance

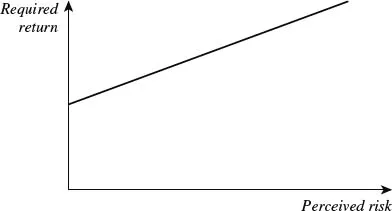

A fundamental principle underlying financial theory is that investors will demand a return commensurate with the risk characteristics that they perceive in their investment. This is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

The diagram in Figure 1.1 is known colloquially as the ‘risk–return line’ and shows the required return for any given level of risk. Although the axes are often referred to as ‘risk’ and ‘return’, it is important to appreciate that their full descriptions are ‘perceived risk’ and ‘required return’. If you do not understand the full extent of the risks that you are taking on an investment, you might settle for a lower required return than another investor with a better appreciation. Alternatively, a sophisticated investor with a great understanding of the low probability of a particularly adverse outcome might settle for a lower return than a naïve investor who runs scared of the downside. What is important is each investor’s perception of the risk; it is in the gaps between their different views that a tailored financial strategy can often add value.

Figure 1.1 The relationship between risk and return.

In a similar fashion the vertical axis in Figure 1.1, often referred to as ‘return’, is actually required return. The very fact that an investment carries a level of risk means that there is no guarantee of its final outcome (risk is generally defined in finance as the volatility of expected outcomes);2 the graph shows what the investor would need in order to match the market expectations.

Financial strategy

We must start this section with a disclaimer: although we will use some strategic models, this is not a book on competitive strategy. Many excellent tomes discuss that subject, setting out the whys and wherefores of determining and pursuing appropriate strategies. This book is about corporate financial strategy and it is in this context that strategy is discussed. However, because we make this distinction, we have to define our terms very clearly, so that you, our readers, are left in no doubt about our purpose.

Consider the representation of a company in Figure 1.2.

To most people, a company is seen as an end in its own right. It serves markets, manufactures products (in this book, for simplicity we use ‘product’ to include service provision), employs staff, and its strategy should be about selecting the most appropriate markets, production facilities, or employees in which to invest. Corporate growth and success – often measured financially in terms of turnover or profit, or by non-financial stakeholders in terms of inputs and outputs – are what’s seen as important, and the business develops a momentum of its own. But Figure 1.2 shows that the investment process does in fact extend over two stages: investors choose the companies in which they want to invest, and the companies choose how to apply those funds to their activities.

For example, as investors we can choose to invest our funds in the UK or elsewhere in the world. We can opt to put our money into the pharmaceutical sector, or into printing or food production or any other sector we choose. And if we do care to be exposed to UK pharmaceutical companies, we can decide specifically, for example, to buy shares in very different companies such as GlaxoSmithKline or Oxford BioMedica. The top process in Figure 1.2 relates to this investor decision.

The lower pr...