![]()

CHAPTER 1

The essentials of language learning

Reading maketh a full man, conference a ready man, and writing an exact man.

(Francis Bacon, Of Studies, 1625)

However carefully planned, if a lesson centres on the teacher for too long, students lose the chance to use what they know. This in turn leads to disenchantment with the subject and reluctance to go on doing it. The inclusion of a language as a core subject in the English Baccalaureate should provide a strong incentive to remedy this situation. However, in the absence of reflection on the central problem of too much teacher-talk, to the detriment of students’ action, any increased uptake is more likely to result from necessity than from real interest in the subject. That is the problem that we seek to tackle in this book. Language-learning research has seen a marked shift in recent years, from a teacher-centred to a learner-centred and now to a learning-centred approach – that we interpret as an approach to teaching and learning that places maximum emphasis on students’ full participation in every activity.

Language learning has a lot in common with craft design technology (CDT): in both, students must develop a firm understanding of basic principles, but the purpose of the whole thing is “doing” – applying knowledge in practical activities. In languages, “doing” means communicating, “Applying linguistic knowledge and skills to understand and communicate effectively”.1 This includes reading and writing, and Chapters 15 to 18 explore ways of using these, but in the classroom communication mainly means talking to fellow-students – “interacting”. Putting such activities at the centre of planning is the key to successful and enjoyable lessons, so the major part of the book (Chapters 7 to 14) concentrates on classroom activities that promote at least partly spontaneous talk.

The Common European Framework (CEF) promotes the use of learning through doing:

The approach adopted here … is an action-oriented one in so far as it views users and learners of a language primarily as ‘social agents’, i.e. members of a society who have tasks (not exclusively language related) to accomplish in a given set of circumstances, in a specific environment and within a particular field of action.2

(CEF, section 2.1, p. 9)

For the CEF, “tasks” are defined as: “actions performed by one or more individuals strategically using their own specific competences to achieve a given result” (ibid.). Such collaborative activities engage students actively in their own learning and help them to develop general skills such as the ability to organise their work, to work by themselves and with others, and to become self-confident in their use of the target language. Furthermore, they correspond neatly to the idea of learning-centred approaches, which is also at the base of three important aims of language learning that are met throughout this book. These are as follows.

• Intercultural understanding: Throughout the book, but especially in Chapters 9 to 18, there are many opportunities to enhance students’ understanding of life as it is lived in the country of the target language, through activities as varied as studying advertisements, planning projects and exploring encyclopaedias. Any authentic input is likely to be loaded with intercultural awareness. This is precisely because it is difficult to divorce the language from the culture, and the language is an entrance to the culture.

• Thinking skills: Chapter 20 lists four specific examples, but numerous other activities require considerable individual or cooperative thought.

• Language learning strategies: Similarly, Chapters 15 (on reading), 19 (on vocabulary and phraseology) and 20 (on grammar) comment specifically on how students learn, but many others require them to put their strategies into action.

Though apparently distinct, these aspects of language learning have in common that all three are dependent on students’ active participation in the activities they undertake, and while they can’t be taught in any formal way, they can be discussed and experimented with. Encouraging reflection on how to learn a word is focusing on strategies for acquiring vocabulary. Discussing how to understand a new word from context involves recognising strategy.

No linguistic task can be carried out without an ever-increasing fund of language, and that goes for all the activities suggested here. One of the best sources of language is independent reading, but words and phrases have to be systematically learnt before they can be used, so this topic is treated at some length in Chapter 19.

What, though, of the basic principles – the understanding of the structures of the language? Understanding and being able to apply “the underlying model” can mean the difference between partial or phrasebook communication and nuanced communication. Although the general teaching of grammar is far too complex a subject to be dealt with fully here, the Chapter 20 of the book deals with possible steps towards mastering the underlying model – “Understanding how a language works and how to manipulate it”3 – and suggests some related tasks. Throughout the book, many of the activities are in fact based on the relationship between communication and structure, which can be made more or less explicit as required. Interestingly, the cognitive approach to language learning is evoked many times in the CEF, reflecting current research in second-language acquisition, particularly in its importance in developing life-long language-learning strategies.

This book naturally concentrates on particular activities, but these will take place in very different environments. Our second chapter therefore considers the physical setting of the classroom and suggests ways of arranging it so as to help you set up these activities. Chapters 3 and 4 then look at aspects of lesson planning and of assessment, before Chapter 5 returns to the main subject of the book.

The later chapters contain a multitude of suggested activities, and we are well aware that this can appear rather overwhelming – you could suffer from un embarras de choix. We appreciate, too, that you are likely to be following a published course book, where the exercises may well not follow the same principles as we do. For this reason we have as far as possible grouped activities together, for example into those showing use of audio-visual resources, or vocabulary and phraseology, or grammatical constructions. You could home in on one of the chapters with most activities, trying them out for a while with any suitable class and topic. Even if you pick an activity almost at random, you should find it quite easy to slant it to support your current objectives. We hope, too, that as you get to know the book better you will recognise that certain exercises fit well with certain topics.

At various places in the text we quote from the 2008 Modern Foreign Languages Programme of Study for Key Stage 3, the crucial link between Key Stage 2 MFL and the examination years. But this does not mean that the approach we recommend is suitable for these years only, important though they are. Active learning is the key to success at any age, so we seldom suggest suitable age- or ability-levels; most activities can be made harder or easier to suit the class.

To sum up: this book is not wedded to any hard-and-fast “method”. At different stages, you could place more emphasis on, say, oral work, grammatical structures or vocabulary/phrase-building, so long as it results in students’ learning to use the language and understand how it works. At its core, the book is a compendium of practical activities designed to help this happen. It does not claim to be thoroughly original: indeed, some of the activities suggested are old favourites, and may even remind you of grandmothers sucking eggs. Other suggestions are perhaps more novel, and a few may appear impossibly difficult “for my class”. Because language cannot be divided into completely separate compartments, some suggestions appear in more than one chapter. But all have the same aim, namely, to provide you with some ideas that you might not otherwise have thought of, and above all to enable students to play a really active role in their own learning. Suggestions that are successful for one teacher or for one class may be less successful for others. We can only say:

Try it, adapt it if it doesn’t work, postpone it if it still doesn’t. Remember, though, thatALL STUDENTS NEED TRAINING IN NEW WAYS OF WORKING, AND THE EARLIER THE BETTER.

Notes

![]()

CHAPTER 2

The classroom environment

The purpose of this book is to suggest strategies to promote students’ active participation in their own learning, mainly through cooperative work. But experience shows that even the best-laid plans can be thwarted by the layout of the classroom. You can set up a carousel of activities (see later in this chapter) – problem solved. But not every room is suitable for carousels, so (at the risk of pointing out the obvious) this chapter begins by suggesting ways of setting up your room to enable students to work together.

Arranging the seating

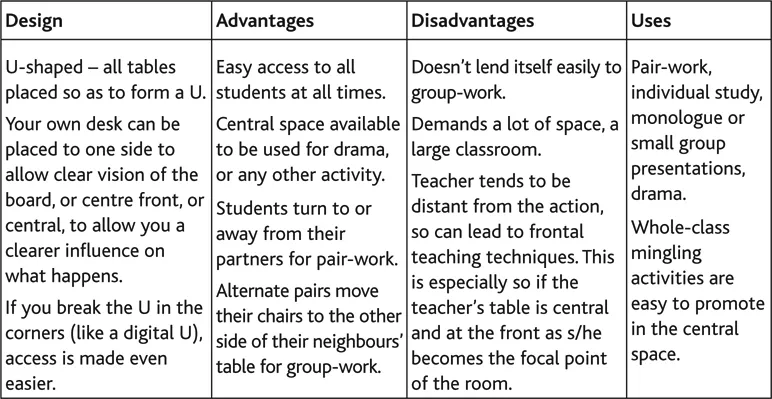

Classrooms come in all shapes and sizes. They also exist within external constraints, such as the ban on moving any furniture on pain of being ostracised by the caretaker staff! If you are lucky enough to have free rein on designing your own arrangements, then you might consider those outlined in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Seating arrangements

Setting up pair-work

(See also Chapters 7 and 8.) Working in pairs usually requires less rearrangement of seating than working in groups, though even here two things are worth considering.

• Should pairs be of equal ability, or is it sometimes better for a more advanced student to partner one less advanced? If the latter, the stronger student can provide very useful guidance, but care must be taken not to create a sense of inferiority in the weaker member.

• How well do the members of the pair know each other? If the exercise requires each to find out things about the other, then it may be better for them not to be “best friends”.

As both these arrangements may involve changing the seating, it helps to give each student a personal number. Seating plans can then be displayed, e.g. on an OHP or whiteboard. Another way of setting up new pairs is for students to draw lots. Half the students put their numbers into a box and the other half draw their partners’ numbers.

Some exercises require students to move, which may mean changing partners in an ordered sequence (e.g., “Multiple partners” in Chapter 8), or full-scale “milling”, where students move freely from one partner to the next, asking questions. In both cases, make sure that the direction of travel is clear to all students. Control the extent of the movement by forming separate smaller clusters, and have clear signals for start and finish.

Setting up group-work

(See also Chapter 9.) Small groups (i.e. three to five) are usually the best setting for students to interact. They also make it much easier for the majority to get on with the task, and more difficult for the less industrious to be a nuisance. In addition, as you move round the class, small groups are the ideal setting for you to forge relationships with students and monitor their progress.

If your classroom is set up in rows, get every other row to turn round to face the row behind; it is then easy to make groups of three or four. Small groups can easily be combined to form larger groups if needed, for example for drama (see Chapter 12).

Carousel working

In carousel working, different areas of the room are set up for different activities. Carousels can be theme-based (all the activities revolve around a central theme, with specific activities to practise all the skills) or can be revision-based (with banks of activities that the student dips into). A certain degree of guided autonomy is promoted by the former, but there is a greater degree of autonomy in ...