![]()

Chapter

1 | Creating value for the customer |

INTRODUCTION

The widespread adoption of the marketing concept by organisations is a relatively recent event. With one or two exceptions marketing literature is barely fifty years old. But during those fifty years the way we think about marketing and the way it is practised has changed significantly. Marketing has progressed from a simplistic focus on ‘giving the customers what they want’ to a pan-company orientation in which the specific capabilities of the business are focused around creating and delivering customer value to targeted market segments.

Philip Kotler, who has probably done more than any writer in the past fifty years to articulate the changes in marketing thinking, captured the essence of conventional marketing in the first edition of his groundbreaking book Marketing Management1in 1967:

Marketing is the analysing, organising, planning and controlling of the firm's customer-impinging resources, policies, and activities with a view to satisfying the needs and wants of chosen customer groups at a profit. In the growth markets of the 1960s and 1970s, the marketers’ challenge was to capture as much of that growth in demand as early as possible. This led them to focus on volume and market share, or what we would now term a ‘transactional’ approach to marketing. As many markets matured in the closing decades of the twentieth century, the emphasis gradually switched from the corporate objective of maximising market share towards a concern with the ‘quality of share’ in recognition of the fact that not all customers are equally profitable. This has led to the notion that the purpose of marketing is to create profitable and enduring relationships with selected customers. A key role of marketing in this new framework is to determine what value propositions to create and deliver to which customers.

Today's marketing-oriented companies are actually ‘market driven’, in the sense that they are structured, organised and managed with the sole purpose of creating and delivering value to chosen markets. Ideas and phrases such as customer intimacy, customer-centric and customer focus summarise the new concept of the corporation as an entity that exists to deliver value to carefully selected market segments. This is not some altruistic or idealistic view of the firm as the provider of customer satisfaction at any cost. Rather it is a hard-edged business model that recognises that long-term profits are more likely to be maximised through satisfied customers who keep returning to spend more money.

This is the backdrop against which the recently emerged paradigm of ‘relationship marketing’ should be viewed.

The evolution of relationship marketing

Marketing literature provides a useful guide to the way marketing theory and practice have developed. In the 1950s frameworks were formulated to manipulate and exploit market demand. The most enduring of these was the idea of the ‘marketing mix’, particularly as enshrined in the shorthand of the ‘4Ps’ of product, price, promotion and place. These were the levers that, if pulled appropriately, would lead to increased demand for the company's offer. Marketing management aimed to devise strategies that would optimise expenditure on the marketing mix to maximise sales.2

The fundamental concept of the marketing mix still applies today in the sense that organisations need to understand and manage the influences on demand. Yet we need to remember that these original frameworks for marketing action were devised in a unique environment. They emerged from the United States during a period of unprecedented growth and prosperity, and focused on fast-moving consumer goods.

But though the tools and techniques developed in a particular era and for particular products might not necessarily be successfully applied more universally, the basic ideas of ‘4Ps marketing’ were rapidly extended into industrial markets,3 then service markets4 and even not-for-profit markets.5

During the closing years of the twentieth century some of these basic tenets of marketing were increasingly being questioned. The marketplace was vastly different from that of the 1950s. In many instances consumers and customers were more sophisticated and less responsive to the traditional marketing pressures – particularly advertising. There was greater choice, partly as a result of the globalisation of markets and new sources of competition. And many markets had matured, in the sense that growth was low or non-existent.

As a result of these and many other pressures, brand loyalty is weaker than it used to be6 and simplistic 4Ps marketing is unlikely to win or retain customers either in consumer or industrial markets. The efficacy of conventional marketing has been repeatedly challenged in articles and conference papers along the lines of ‘Is marketing dead?’7, 8

It is against this background that the new wave of marketing thinking has become apparent, and the label ‘relationship marketing’ applied to describe the revised framework or paradigm.9

In the earlier edition of this book,10 we developed a general model of relationship marketing. We have since refined it, but it still embodies the following elements. Relationship marketing:

emphasises a relationship, rather than a transactional, approach to marketing;

understands the economics of customer retention and thus ensures the right amount of money and other resources are appropriately allocated between the two tasks of retaining and attracting customers;

highlights the critical role of internal marketing in achieving external marketing success;

extends the principles of relationship marketing to a range of diverse market domains, not just customer markets;

recognises that quality, customer service and marketing need to be much more closely integrated;

illustrates how the traditional marketing mix concept of the 4Ps does not adequately capture all the key elements which must be addressed in building and sustaining relationships with markets;

ensures that marketing is considered in a cross-functional context.

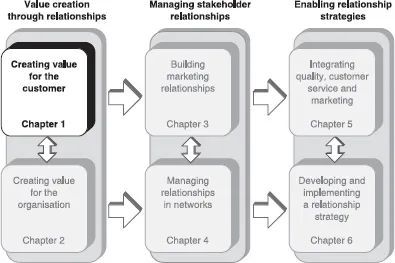

This broader concept of relationship marketing is depicted in Figure 1.1.

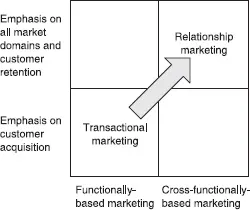

FIGURE 1.1 The transition to relationship marketing

The fundamental principles of relationship marketing

As Figure 1.1 suggests, a number of characteristics distinguish relationship marketing from earlier frameworks. The first is an emphasis on extending the ‘lifetime value’ of customers through strategies that focus on retaining targeted customers. The second is the recognition that companies need to forge relationships with a number of market domains or ‘stakeholders’ if they are to achieve long-term success in the final marketplace. And the third is that marketing has moved from being the sole responsibility of the marketing department to become ‘pan-company’ and cross-functional.

Maximising the lifetime value of a customer is a fundamental goal of relationship marketing.

Maximising the lifetime value of a customer is a fundamental goal of relationship marketing. In this context, we define the lifetime value of a customer as the future flow of net profit, discounted back to the present, that can be attributed to a specific customer. Adopting the principle of maximising customer lifetime value forces the organisation to recognise that not all customers are equally profitable and that it must devise strategies to enhance the profitability of those customers it seeks to target. We go on to explore these ideas in more depth in Chapter 2. But, in essence, companies need to tailor and customise their relationship marketing strategies even to the extent of so called ‘one-to-one’ marketing.11

The second differentiating feature of relationship marketing is the concept of focusing marketing action on multiple markets. Conventionally, marketing strategy has been structured solely around the customer. Of course, the ultimate aim of relationship marketing strategies is to compete successfully for profitable customers. But to do this firms need to define more broadly the markets that need to be addressed. Relationship marketing recognises that multiple market domains can directly or indirectly affect a business's ability to win or retain profitable customers. These other markets include suppliers, employees, influencers, distributors and alliance partners. We have previously defined10 this multiple market focus as the ‘six markets model’. But there is nothing sacrosanct about the number six, and in any given circumstance firms may need to encompass fewer or more ‘stakeholders’ within their overall relationship marketing strategies. We explore the concept of the multiple market model in greater detail in Chapter 3.

The third key element of relationship marketing is that it must be cross-functional.

David Packard, a co-founder of Hewlett-Packard, is reported to have said that ‘marketing is too important to be left to the marketing department’. You could interpret this in a number of ways (for example, the marketing department is not up to the task!) but we choose to understand it as a call to bring marketing out of its functional silo and inculcate the concept and the philosophy of marketing across the business.

In practice this needs to be accompanied by an organisational change that fosters cross-functional working and develops the mindset that everyone within the business serves a customer, be they internal or external customers.

In addition to these three key differentia...