![]()

Chapter 1

From research to implications

We’ve always worried about the impact of new technologies on language, literacy, education and society at large. Socrates feared that writing, the new technology of his day, would lead to a decline in memorisation and an impoverishment of discussion. The Bible, ironically, includes one of the earliest complaints about books, wearily proclaiming that ‘of making many books there is no end’ (Ecclesiastes 12:12), while in ancient Rome Seneca warned that ‘in reading of many books is distraction’ (1917, p. 7). But it wasn’t until the arrival of Gutenberg’s printing press in the 1400s that the number of books really exploded – along with concerns about them. During the Renaissance, Dutch humanist Erasmus worried about printers flooding the world with ‘stupid, ignorant, slanderous, scandalous, raving, irreligious and seditious books’ (1964, p. 184). Martin Luther saw it this way:

The multitude of books is a great evil. There is no measure or limit to this fever for writing; every one must be an author; some out of vanity, to acquire celebrity and raise up a name; others for the sake of lucre and gain. (1857, p. 369)

Complaints of being overloaded with trivia continued for centuries, with French theologian John Calvin bemoaning the ‘confused forest of books’ (cited in Blair, 2010, Kindle location 1348), German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz protesting the ‘horrible mass of books’ (ibid., Kindle location 1411) and English poet Alexander Pope grumbling about a ‘deluge of authors’ (1729, p. 55).

But it’s not just books that once seemed iniquitous. The same pattern has repeated itself with the arrival of each new communications technology. The deleterious effects of the telegraph were trumpeted in the Spectator in 1889: ‘The constant diffusion of statements in snippets … must in the end, one would think, deteriorate the intelligence of all to whom the telegraph appeal[s]’ (cited in Morozov, 2011, Kindle location 4588). Postcards, it was claimed, would undermine letter writing. The telephone, it was feared, would encourage inappropriate social contacts. Comic books, it seemed, would lead to juvenile delinquency. And then came television, and CDs, and mobile phones …

With a few small changes, most of the comments quoted above could be drafted into the contemporary media assault on Wikipedia and YouTube, Facebook and Twitter, chat and text messaging. Like all past communications technologies, our new digital tools will be associated with changes in language, literacy, education and society. Indeed, they already are. Some observers perceive losses, such as a decline in more linear approaches to reading or more reflective approaches to writing. But others perceive gains, such as education through personal learning networks (PLNs), or collaborative projects based on collective intelligence. Eventually, the day will come when our new tools are so enmeshed in our routine language and literacy practices that we’ll barely notice them any more. But that day is still some way off.

A framework of digital literacies

We’re preparing students for a future whose outlines are, at best, hazy. We don’t know what new jobs will exist. We don’t know what new social and political problems will emerge. However, we’re starting to develop a much clearer picture of the competencies needed to participate in digitally networked post-industrial economies and societies. Governments, ministries of education, employers and researchers are all calling for the promotion of twenty-first-century skills such as creativity and innovation; critical thinking and problem-solving; collaboration and teamwork; autonomy and flexibility; and lifelong learning. At the heart of this complex of skills is an ability to engage with digital technologies, which requires a command of the digital literacies necessary to use these technologies effectively to locate resources, communicate ideas, and build collaborations across personal, social, economic, political and cultural boundaries. In order to engage fully in social networks, gain employment in post-industrial knowledge economies, and assume roles as global citizens who are comfortable with negotiating intercultural differences, our students need a full suite of digital literacies at their disposal.

Digital literacies: the individual and social skills needed to effectively interpret, manage, share and create meaning in the growing range of digital communication channels.

Notwithstanding the views of politicians and pundits who cling to an older notion of literacy as a monolithic, print-based skillset, it is increasingly widely accepted that literacy is a plural concept (Kalantzis and Cope, 2012; Lankshear and Knobel, 2011; Pegrum, 2011), a point which has taken on added significance in the digital era. It has also become increasingly apparent that literacies are not just individual skills or competencies but social practices (Barton, 1994; Barton and Hamilton, 2000; Rheingold, 2012), another point which has become more salient thanks to the rise of the participatory web 2.0 around the turn of the millennium. In the preceding decades we had already begun to talk of specific literacies like ‘visual literacy’, ‘media literacy’, ‘information literacy’ and ‘multiliteracies’, but with the advent of web 2.0 came an explosion of interest in new – especially digital – literacies. This has led to discussions of a whole slew of particular literacies ranging from ‘remix literacy’ (Lessig, 2007) and ‘personal literacy’ (Burniske, 2008) to ‘attention literacy’ (Rheingold, 2009b), ‘network literacy’ (Pegrum, 2010; Rheingold, 2009a) and ‘mobile literacy’ (Parry, 2011).

Web 2.0: a new generation of web-based tools like blogs, wikis and social networking sites, which focus on communication, sharing and collaboration, thus turning ordinary web users from passive consumers of information into active contributors to a shared culture (see Box 1.1).

‘Reading is an unnatural act; we are no more evolved to read books than we are to use computers’, Clay Shirky (2010b) reminds us. As he goes on to point out, we spend a great deal of time and effort developing reading (and, of course, writing) skills – in short, what we might call print literacy – in children, and it’s now time to do the same with digital literacies. Language and literacy are tightly bound up with each other: partly because the very notion of literacy is grounded in language, and partly because all literacies are connected with the communication of meaning, whether through language or other, frequently complementary channels. Neither language nor literacy is disappearing. As James Gee and Elisabeth Hayes (2011) observe, language is actually ‘powered up’ or ‘levelled up’ by digital media. Digital literacy, then, is even more powerful and empowering than analogue literacy. We need to level up our teaching and our students’ learning accordingly. For our language teaching to remain relevant, our lessons must encompass a wide variety of literacies which go well beyond traditional print literacy. To teach language solely through print literacy is, in the current era, to short-change our students on their present and future needs.

Box 1.1 What hardware and software do I need?

More on web 2.0

URL: goo.gl/LO0JM

In addition to an internet connection, teachers and students need adequate hardware. Gradually, desktop computers (which traditionally rely on hardwired internet connections) have lost market share to laptops (which mostly rely on wireless networks). In turn, laptops are now ceding space to mobile handheld devices (which rely on wireless and/or 3G and 4G networks). Mobile handheld devices encompass tablets, such as the iPad, and mobile phones, including smartphones like the iPhone, Android phones and BlackBerry phones. In high-tech educational contexts, there is a clear trend towards dismantling fixed computer labs and instead using laptops and mobile handheld devices, which are often student-owned rather than institutionally owned. Some institutions are starting to shift towards a BYOD (Bring Your Own Device) model, where each student brings their own device chosen from a range determined by the institution, or a BYOT (Bring Your Own Technology) model, where there are few if any restrictions on the range of web-enabled devices students can bring into the classroom to support their learning (see Chapter 3: Teaching in technology-limited environments). In low-tech contexts, some educators are also exploring the potential of mobile phones, as well as working with devices such as the inexpensive XO laptops developed by the One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) project to help address the global divide in digital access (see Box 1.4).

The world wide web, or simply the web, is one of the dominant services running on the internet. It is made of up of millions of interlinked websites. Nowadays many teachers primarily use free or low-cost web 2.0 services in their lessons. The hardware devices mentioned above allow web access through software called a web browser; examples include Apple’s Safari, Google’s Chrome, Microsoft’s Internet Explorer and Mozilla’s Firefox. Although many mobile handheld devices also include web browsers, such devices increasingly work with applications, or apps, that is, small pieces of software which are downloaded from the internet, have specific and limited functionality (as opposed to the general functionality of a web browser), may run with or without web access, and are typically inexpensive or even free (see Chapter 1: First focus: Language, Mobile literacy).

Other common hardware includes data projectors, which project a computer’s display onto a large screen, for example at the front of a classroom. A more flexible option is offered by touch-sensitive interactive whiteboards, or IWBs, which, operating in conjunction with data projectors, can be used to display and interact with webpages or software running on the connected computer, as well as capturing and saving notes. Clickers, also known by the fuller name of personal response systems, allow student responses to questions to be displayed on a screen or smartboard. A new development with some educational potential is the emergence of 3D printers.

The proliferation of digital hardware, software and internet connections, especially coupled with the availability of free or cheap web 2.0 services and mobile apps, is good news for teachers everywhere.

Neil Selwyn notes that there are external and internal imperatives for incorporating digital technologies into education. External imperatives concern the need to prepare our students for social life, employment and citizenship in the digitally networked world outside the classroom. It is largely due to such external imperatives, particularly economic ones, that school curricula around the world are beginning to emphasise the importance of digital competencies and new literacies (Belshaw, 2011; Selwyn, 2011). Internal imperatives concern the benefits digital technologies can offer within the classroom, chiefly by supporting constructivist, student-centred pedagogical approaches (see Box 2.1). Digital literacies, we suggest, are linked to both imperatives: they’re essential skills our students need to acquire for full participation in the world beyond the classroom, but they can also enrich our students’ learning inside the classroom.

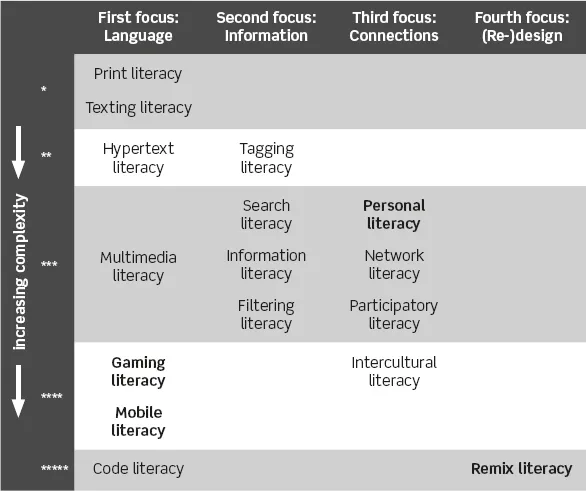

In Chapter 1, we’ll discuss the major literacies our students need to acquire (based on Pegrum, 2009 and 2011). The literacies are grouped loosely under four focus points – language, information, connections and (re-)design – and arranged loosely in order of increasing complexity under those focus points, as can be seen in Table 1.1. The considerations which have led to this particular ordering are examined in more detail later (see Chapter 3: Choosing activities for different levels and contexts, Overall complexity). The framework is not intended as a checklist of distinct literacies – many of these literacies blur into each other, as indeed do the four focus points – but rather as a map of key areas of emphasis we need to consider within the overall field of digital literacies. While many of the literacies involve elements of other literacies, those which are most obviously macroliteracies – that is, which pull together a number of other literacies – are shown in bold in the table. Whether we are teaching students about literacies or macroliteracies, Table 1.1 Framework of digital literacies our task is to help them develop strategies to deal with each key area so they can make the most of the possibilities of digital media. Of course, some literacies involve skillsets that language teachers have been promoting for decades, but which have come to greater prominence in recent years. Intercultural literacy, for example, has become all the more important in a world where technology often highlights, rather than erases, cultural and other differences.

Table 1.1 Framework of digital literacies

After these skills and associated strategies have been outlined in Chapter 1, Chapter 2 offers some practical starting points for those who are not very familiar with new technologies and new literacies. It includes numerous activities, often based on activities well known to teachers, where digital literacies can be fostered side by side with traditional literacy skills. If you’re more confident, you may wish to try out some of the more challenging activities suggested. While the activities included in Chapter 2 are designed primarily for teachers and learners of English as an additional, other, second or foreign language (with the most common nomenclature varying across contexts), most are easily transferable ...