![]()

Introduction

Key points

● the nature of law

● custom, morality and the law

● classification of law

● characteristics of English law

1.1 The nature of law

The term ‘law’ is used in many senses: we may speak of the laws of physics, mathematics, science or the laws of football. When we speak of the law of a State we use the term ‘law’ in a special and strict sense, and in that sense law may be defined as a rule of human conduct, imposed upon and enforced among the members of a given State.

People are by nature social animals desiring the companionship of others, and in primitive times they tended to form tribes, groups or societies, either for self-preservation or by reason of social instinct.

If a group or society is to continue, some form of social order is necessary. Rules or laws are, therefore, drawn up to ensure that members of the society may live and work together in an orderly and peaceable manner. The larger the community (or group or State), the more complex and numerous will be the rules.

If the rules or laws are broken, compulsion is used to enforce obedience. We may say, then, that two ideas underline the concept of law: (a) order, in the sense of method or system; and (b) compulsion – i.e. the enforcement of obedience to the rules or laws laid down.

1.2 Custom, morality and law

On examination of the definition of law given above certain important points should be noted.

(a) Law is a body of rules

When referring to ‘the law’ we usually imply the whole of the law, however it may have been formed. As we shall see later, much of English law was formed out of the customs of the people. But a great part of the law has been created by legislation, i.e. the passing of laws. Common law and statutory law together comprise what is referred to as the ‘Law of England’.

(b) Law is for the guidance of human conduct

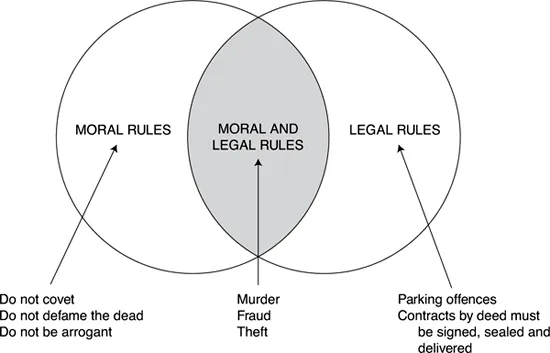

People resort to various kinds of rules to guide their lives. Thus moral rules and ethics remind us that it is immoral or wrong to covet, to tell lies or to engage in drunkenness in private. Society may well disapprove of the transgression of these moral or ethical precepts. The law, however, is not concerned with such matters and leaves them to the individual’s conscience or moral choice and the pressure of public opinion: no legal action results (unless a person tells lies under oath in a court, when he or she may be prosecuted for perjury). Thus there is a degree of overlap between moral and legal rules, as depicted by the diagram ‘Moral and legal rules’.

Sometimes Parliament does intervene as illustrated by the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008 which abolished the common law offences of blasphemy and blasphemous libel (s. 79).

(c) Law is imposed

We sometimes think of laws as being laid down by some authority such as a monarch, dictator or group of people in whom special power is vested. In Britain we can point to legislation for examples of law laid down by a sovereign body, namely Parliament. The legal author John Austin (1790–1859) asserted that law was a command of a sovereign and that citizens were under a duty to obey that command. Other writers say that men and women in primitive societies formed rules themselves, i.e. that the rules or laws sprang from within the group itself. Only later were such rules laid down by a sovereign authority and imposed on the group or people subject to them.

(d) Enforcement

Clearly unless a law is enforced it loses its effectiveness as a law and those persons subject to it will regard it as dead. The chief characteristic of law is that it is enforced, such enforcement being today carried out by the State. Thus if A steals a wallet from B, A may be prosecuted before the court and may be punished. The court may then order the restitution of the wallet to its rightful owner, B. The ‘force’ used is known as a sanction and it is this sanction that the State administers to secure obedience to its rules.

(e) The State

A State is a territorial division in which a community or people lives subject to a uniform system of law administered by a sovereign authority, e.g. a parliament.

FIGURE 1.1 Moral and legal rules

The United Kingdom, which comprises a parliamentary union of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, is for our purposes the State. Parliament at Westminster legislates for England, Scotland and Wales, (although, in accordance with recent devolution legislation, Scotland and Wales now have separate parliamentary assemblies which are empowered to legislate with regard to specified internal affairs such as education), and also in respect of some matters (such as defence and coinage) for Northern Ireland. Scotland has its own legal system, different in many ways from that of England and Wales, and has been influenced by Roman and Continental law to a far greater extent.

(f) Content of law

The law is a living thing and it changes through the course of history. Changes are brought about by various factors such as invasion, contact with other races, material prosperity, education, the advent of new machines or new ideas or new religions. Law responds to public opinion and changes accordingly. Formerly the judges themselves moulded and developed the law. Today an Act of Parliament may be passed to change it.

(g) Justice and law

People desire justice in their personal, social and economic dealings. There is no universal agreement on the meaning of justice, and ideal or perfect justice is difficult to attain in this life. People strive for relative justice, not perfect justice; and good laws assist to that end. It is the business of citizens in a democracy to ensure that wise laws are passed and that they are fairly administered in the courts of law.

1.3 Classification of law

Law may be classified in various ways. The four main divisions are as follows:

(a) criminal law and civil law

(b) public law and private law

(c) substantive law and procedural law

(d) municipal law and public international law

(a) Criminal law

Criminal law is that part of the law that characterizes certain kinds of wrongdoings as offences against the State, not necessarily violating any private right, and punishable by the State. Crime is defined as an act of disobedience of the law forbidden under pain of punishment. The punishment for crime ranges from death or imprisonment to a money penalty (fine) or absolute discharge. For example, to commit murder is an offence against the State because it disturbs the public peace and security, so the action is brought by the State and not the victim.

The police are the public servants whose duty is the prevention and detection of crime and the prosecution of offenders before the courts of law. Private citizens may legally enforce the criminal law by beginning proceedings themselves, but, except in minor cases of common assault, rarely do so in practice.

Civil law is concerned with the rights and duties of individuals towards each other. It includes the following:

(i) Law of contract, dealing with that branch of the law that determines whether a promise is legally enforceable and what are its legal consequences.

(ii) Law of tort. A tort is defined as a civil wrong for which the remedy is a common law action for unliquidated (i.e. unspecified or unascertained) damages and which is not exclusively the breach of a contract or breach of trust or other merely equitable obligation. (Salmond: Law of Torts.) Examples of torts are: nuisance, negligence, defamation and trespass.

(iii) Law of property is that part of the law that determines the nature and extent of the rights that people may enjoy over land and other property – for example, rights of ‘ownership’ of land, or rights under a lease.

(iv) Law of succession is that part of the law that determines the devolution of property on the death of the former owner.

(v) Family law is that branch of the law that defines the rights, duties and status of husband and wife, parent and child, and other members of a household.

The above are the major branches of civil law. Its main distinction from criminal law is that in civil law the legal action is begun by the private citizen to establish rights (in which the State is not primarily concerned) against another citizen or group of citizens, whereas criminal law is enforced on behalf of or in the name of the State. Civil law is sometimes referred to as priva...