- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Q&A Jurisprudence

About this book

Routledge Q&As give you the tools to practice and refine your exam technique, showing you how to apply your knowledge to maximum effect in assessment. Each book contains essay and problem-based questions on the most commonly examined topics, complete with expert guidance and model answers that help you to:

Plan your revision and know what examiners are looking for:

-

- Introducing how best to approach revision in each subject

-

- Identifying and explaining the main elements of each question, and providing marker annotation to show how examiners will read your answer

Understand and remember the law:

-

- Using memorable diagram overviews for each answer to demonstrate how the law fits together and how best to structure your answer

Gain marks and understand areas of debate:

-

- Providing revision tips and advice to help you aim higher in essays and exams

-

- Highlighting areas that are contentious and on which you will need to form an opinion

Avoid common errors:

-

- Identifying common pitfalls students encounter in class and in assessment

The series is supported by an online resource that allows you to test your progress during the run-up to exams. Features include: multiple choice questions, bonus Q&As and podcasts.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 | General Aspects of Jurisprudence |

INTRODUCTION

This chapter offers only one question, but it is perhaps the most important question in this book. The most important general advice to any new student to the subject of jurisprudence is to identify the viewpoint of the legal theorist. Identifying the legal theorist’s viewpoint on law will prevent confusion and many misunderstandings.

QUESTION 1

How does an insight into the ‘viewpoint’ of a legal theorist concerning law help in understanding the work of the legal theorist?

How to Answer this Question

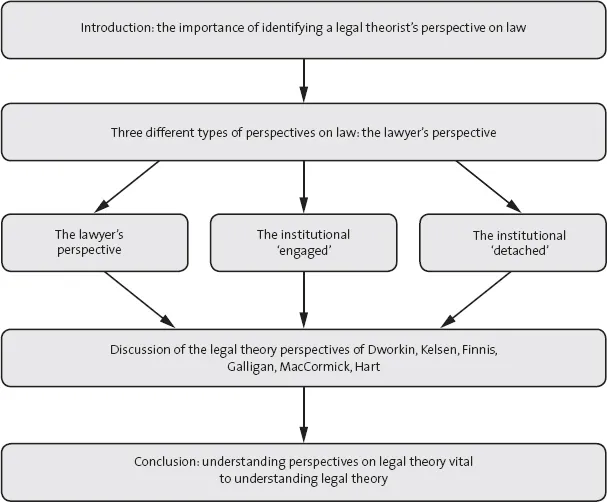

The question concerns the general question of the role that a legal theorist’s viewpoint has on the understanding of the legal theorist’s theory of law. The answer identifies three general viewpoints that a legal theorist might take on the institution we call ‘law’:

(1) the lawyers or participant’s perspective where the legal theorist seeks to explain law in terms of a lawyer’s understanding of law. Dworkin and Kelsen are the best known examples of this perspective;

(2) the institutional ‘engaged’ perspective is where the legal theorist goes beyond the lawyer’s perspective and examines law in its wider political and social perspective, but this perspective has a strong commitment to a particular type of legal system or an ideal form of law. Finnis, Galligan and MacCormick are all strong examples of this type of approach;

(3) the ‘detached’ institutional perspective where the legal theorist examines law in its social and political context – the ‘institutional setting of law’ – but has no express commitment to law or legal systems of any kind. This value-free descriptive jurisprudence is best exemplified by Professor Hart.

Applying the Law

ANSWER

Jurisprudence can seem bewildering to the new student as a mass of theorists and theories are suddenly thrust upon them and they are expected to absorb, digest and feedback a body of knowledge that seems part philosophy, part sociology and part history, while bearing little relation to traditional law subjects.

One way of imposing order upon the chaos is to try to obtain a sense of where a particular legal theorist stands in relation to the law. Understanding the standpoint of a legal theorist makes understanding that legal theorist easier and allows the construction of a ‘mind map’ so that important jurisprudential scholars can fit into that ‘mind map’ schemata.

It is suggested that three broad standpoints could be identified in order to place a range of authors in a ‘viewpoint mind map’. These authors include: Dworkin, Kelsen, Galligan, MacCormick, Finnis, Austin, Hart and Raz.

The three viewpoints or standpoint perspectives are:

(1) participant perspectives – Dworkin, Kelsen;

(2) institutional (or ‘external’) engaged perspective – MacCormick, Galligan, Finnis;

(3) institutional (or ‘external’) detached perspective – Hart, Austin.

The participant perspective can also be termed the ‘lawyer’s perspective’. This perspective seeks to give an account of the social institution we call law from the point of view of the court-room or a judge. To a certain extent this perspective is a ‘natural’ one for a legal theorist to take. As Professor Raz comments in ‘The Nature of Law’ in Ethics in the Public Domain (1994):

‘most theorists tend to be by education and profession lawyers, and their audience often consists primarily of law students. Quite naturally and imperceptibly they adopted the lawyers perspective on the law.’

The problem with the participant or lawyer’s perspective on the law is that it can lead the legal theorist who adopts it to neglect important features of law because the lawyer’s perspective fails to examine the law in the wider political context in which the law is moored. Two legal theorists who adopted the lawyer’s perspective are Hans Kelsen and Ronald Dworkin.

Kelsen took explaining the ‘normativity’ or authority of the law as the backbone of his theory of law. This in itself is a question which looks at law from the lawyer’s perspective – what sense, Kelsen asked, to give to claims of ‘ought’ in the law? As Kelsen comments in Introduction to the Problems of Legal Theory (1934):

‘The Pure Theory of Law works with this basic norm as a hypothetical foundation. Given this presupposition that the basic norm is valid, the legal system resting on it is also valid … Rooted in the basic norm, ultimately, is the normative import of all the material facts constituting the legal system. The empirical data given to legal interpretation can be interpreted as law, that is, as a system of basic norms, only if a basic norm is presupposed.’

Therefore Kelsen, a person who regards a legal order as valid as opposed to a mere coercive order, presupposes a hypothetical ‘basic norm’ which gives ‘normativity’ or ‘oughtness’ to the legal system so interpreted as valid. Kelsen is seeking to explain what lawyers mean when they say ‘the law says you ought not to do X or you ought to do X’. Kelsen’s persepective is the lawyer’s perspective, trying to give sense to ‘lawyers’ talk’ of legal obligation. As Kelsen comments in Pure Theory of Law (1967) ‘the decisive question’ is why the demands of a legal organ are considered valid but not the demands of a gang of robbers. The answer to this question is that only the demands of a legal organ are interpreted as an objectively valid norm because the person viewing the legal order as valid and therefore more than a coercive order from a ‘gang of robbers’ is presupposing in his own consciousness a basic norm which gives validity and normative force to the legal order.

Kelsen’s basic question in legal theory – what sense to give to lawyers’ statements of ‘legal ought’ – is a question from the lawyer’s perspective, but this tendency to examine the law from the lawyer’s or participant’s perspective is reinforced by Kelsen’s methodology. Kelsen insisted that his theory was a ‘pure theory of law’. He regarded it as doubly pure – pure of all moral argument and pure of all sociological facts. The view of law examined by Kelsen is free of any kind of moral evaluation, such as what moral purposes the law could serve, or sociological enquiry as for example what motivates persons to obey the law. Kelsen merely looks at the raw data of legal experience to be found in the statute books and law reports and asks: what sense to give to legal talk of ‘ought’?

For a legal theory to ignore the moral and sociological realities framing the law it must be the case that that legal theory is focusing purely on the lawyer’s perspective. Although Kelsen has an interesting and developed theory answering the lawyer’s question of what sense to give to lawyers’ talk of legal obligation, legal duty and legal ‘ought’, Kelsen’s theory of law has little general explanatory power of the social institution called law. Moreover, by clinging so exclusively to the ‘lawyer’s perspective’ Kelsen makes statements that, from a wider perspective, seem unjustifiable. For example Kelsen comments, in Introduction to the Problems of Legal Theory (1934), that:

‘the law is a coercive apparatus having in and of itself no political or ethical value.’

Kelsen should have considered that the law can have value in itself as a means by which citizens can express loyalty and identification with their community. This point, recognised by modern writers on law such as Raz and Leslie Green, would have been lost on Kelsen – buried as he was in the lawyer’s perspective.

Kelsen’s theory of law was once termed by the political thinker Harold Laski as ‘an exercise in logic not in life’ (see Laski, A Grammar of Politics (1938)). We may interpret this statement by Laski as meaning that although Kelsen tries impressively to answer the question concerning the law’s normativity, Kelsen has little of value to say about law as a social phenomenon generally.

The lawyer or participant viewpoint on law can be valuable but it is unreasonable to study the law solely and exclusively from the lawyer’s perspective. The law must be examined, in order to get full explanatory power of this important social institution, in the wider perspective of social organisations and political institutions generally. This wider perspective may be termed the ‘institutional’ or ‘external’ perspective on law and has been the dominant viewpoint in English jurisprudence from Thomas Hobbes in the seventeenth century to Professor Hart.1

However, before we examine the ‘institutional’ perspective on law we need to examine another famous example of the lawyer’s perspective – Professor Ronald Dworkin’s theory of law.

Dworkin’s preoccupation with his theory of law has been to answer the question: how can law be interpreted so as to provide a sound justification for the use of state coercion involved in forcing the payment of compensation in a civil action at law? This is again a lawyer’s question, although a different lawyer’s question from Kelsen’s preoccupation with the normativity of the law. Dworkin’s theory of law is aimed at the justification of state coercion expressed through law. Dworkin has taken appellate case decisions as the testing ground for his theory of law which has involved the controversial proposition that the law of the Anglo-American legal system involves not just the accepted case law and statutes but also the law that includes the best moral interpretation of that law. Therefore there is a greater connection between Dworkin’s lawyer’s perspective and general legal theory than Kelsen’s lawyer’s perspective which seemed grounded on the normativity of law only. Dworkin’s theory of law at least engages with the debate ‘what is law?’ or ‘what are the grounds of law?’ However, despite Dworkin’s connection to wider debates in legal theory about the nature of law, Dworkin seeks to answer that question from the lawyer’s perspective. Dworkin has defended his preoccupation with the courtroom2 by observing that it is in the courtroom that the doctrinal question of ‘what is law?’ is most acutely answered. Dworkin comments in ‘Hart and the Concepts of Law’ (2006) Harvard Law Review Forum:

‘Courtrooms symbolise the practical importance of the doctrinal question and I have often used judicial decisions both as empirical data and illustrations for my doctrinal claims.’

Dworkin has often used appellate cases to support his arguments, leading to the charge that he is developing a legal theory out of a theory of adjudication. Dworkin uses the House of Lords appellate case of McLouglinh v O’Brien (1982) as the centrepiece for testing various theories of law, including his own theory known as ‘law as Integrity’ at pp. 230–240 of Law’s Empire – Dworkin’s magnum opus on legal theory from 1986. The United States appellate court decisions of the Supreme Court have been used by Dworkin, namely: the ‘snail darter’ case Tennessee Valley Authority v Hill (1978) and Brown v U.S. (1954) are both discussed by Dworkin in Law’s Empire at pp. 20–23 and pp. 29–30 respectively. A case used by Dworkin in the 1960s to illustrate these arguments about the nature of law – ‘Elmer’s case’ – is used again at pp. 15–20 of Law’s Empire. ‘Elmer’s case’, known properly as Riggs v Palmer (1883) is an appellate decision of the New York appeals court.

Dworkin’s lawyer’s perspective on the law and his tendency to look at the law through the prism of the courtroom has led to criticism that Dworkin has developed a theory of law out of a theory of adjudication. As Professor Raz argues in Between Authority and Interpretation (2009):

‘[Dworkin’s] book is not so much an explanation of the law as a sustained argument about how courts, especially American and British courts should decide cases. It contains a theory of adjudication rather than a theory of the nature of law.’

The argument against Dworkin is that his obsession with the courtroom – the lawyer’s perspective on law – means that Dworkin can miss, or fail to appreciate, essential features of law that operate in the wider social context beyond the courtroom. For example, Dworkin fails in his legal theory to account for the law’s claim to authority which is an important part of the law’s method of social organisation. Dworkin says a lot about the need for the law to have ‘integrity’ or ‘fairness’ but little about the law’s authority. Although the integrity or fairness of the law is vital, so is the law’s authority. If Dworkin had stepped back from the lawyer’s perspective he might have seen this point.

The institutional perspective stands back from the lawyer’s perspective, not in order to disregard it, but to examine lawyers and courts in the wider perspective of their place in the social organisation and political institutions of a society.

The ‘institutional’ perspective has had many representatives in the history of legal philosophy. Its influence started with Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan (1651) who heavily influenced Bentham (Of Laws in General (1782)) and Austin (The Province of Jurisprudence Determined (1832)). Hobbes placed law in its wider political context and argued that strong authority was needed to pacify a society, for without a common authority to keep men ‘in awe’ the natural tendency of man was to war with his fellow men. Once the strong authority – the ‘Leviathan’ (from the Book of Job, Chapter 41, Old Testament: ‘Leviathan’ meaning a great sea beast – so the state by analogy is something which should be overwhelmingly powerful and awe-inspiring to people) – was established then the laws were the commands of the sovereign authority designed to maintain civil peace. Hobbes thus provided an account of law in terms of political and social needs. Austin and Bentham continued this tradition. Austin and Bentham first of all identified the sovereign in a society by considering ‘habits of obedience’ in that society and then in the tradition of Thomas Hobbes, identified the law as the ‘commands of the sovereign’. If Austin and Bentham’s account of law is too ‘thin’, i.e. lacks explanatory power, it is not because of the ‘institutional’ perspective they adopted with regard to law but because the terms they employed in their description of law – ‘sovereign’, ‘habits of obedience’, ‘sanctions’, ‘commands’ – were too few in number and too simplistic to give an adequate descriptive analysis of law and legal systems.

Austin and Bentham explained the nature of the political system and then proceed to explain the nature of law by placing it within the political system. HLA Hart continued that ‘institutional’ tradition by examining law against the context of social and political needs. For example, Hart has a famous ‘fable’ in The Concept of Law (1961) to show the general social benefits a system of law might bring to a society governed by social rules only. Those benefits include the ability to change rules quickly through Parliamentary amendment and procedures to determine the exact scope of a social rule through the setting up of a court structure. Hart also shows how different legal rules help to plan social life out of court through laws on contract, marriages and wills, for exa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Table of Cases

- Table of Legislation

- Guide to the Companion Website

- Introduction

- 1 General Aspects of Jurisprudence

- 2 The Nature of Law

- 3 Legal Positivism

- 4 Natural Law

- 5 Law and Ideology

- 6 Authority

- 7 Human Rights and Legal Theory

- 8 Common Law and Statute

- 9 Liberalism, Toleration and Punishment

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Q&A Jurisprudence by David Brooke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Jurisprudence. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.