1 Introduction

What is organizational or work psychology?

Most of us are born and die in organizations. We are educated and work in organizations. We spend a great deal of our in leisure time playing and praying in organizations. Furthermore, one of the largest and most powerful of organizations – the government or state – prescribes and proscribes how we should behave throughout our lives. We are shaped, nurtured, controlled, rewarded and punished by organizations all our lives. We are social animals who live in groups most of which might be called organizations.

Just after the Second World War, work psychology was conceived in terms of two simple and memorable epithets: “fitting the person to the job” and “fitting the job to the person”. Today this would be called vocational and occupational psychology, management and ergonomics. But what do we understand work psychology to be today halfway through the first decade of the first century of the second millennium? Three ways of discovering the nature of work psychology is to look at definitions of it, how different academic disciplines contribute to it, and the subfields of work psychology.

Textbook definitions on the topic differ considerably. Consider the following:

• Cherrington (1989: 27): “The field of organizational behavior developed primarily from the contributions of psychology, sociology, and anthropology. Each of these three disciplines contributed ideas relevant to – organizational events that were combined into a separate study called organizational behavior. Three other disciplines that had a minor influence on the development of organizational behavior included economics, political science and history”.

• Jewell (1985: 10): “Organizational behavior (work psychology) is a specialty area within the study of management. The difference between I/O [industrial/organizational] psychology as a subject for study and organizational behavior is not difficult to define conceptually. Industrial/organizational psychologists are interested in human behavior in general and human behavior in organizations in particular. Organizational behaviorists are interested in organizations in general and in the people component of organizations in particular. The basic distinction between I/O psychology and organizational behavior as academic areas of study is often difficult to maintain in applied organizational settings. The American Psychological Association formally recognized the interrelatedness of these two approaches to the same basic problems in 1973. At that time, the old designation of industrial psychology was replaced with the term now in standard use, industrial/organizational psychology”.

• Baron & Greenberg (1990: 4): “The field of organizational behavior seeks knowledge of all aspects of behavior in organizational settings through systematic study of individual, group and organizational processes; the primary goals of such knowledge are enhancing effectiveness and individual well being”.

• Spector (2003: 6): “The field of I/O psychology has a dual nature. First, it is the science of people at work. This aspect ties it to other areas of psychology, such as cognitive and social. Second I/O psychology is the application of psychological principles to organizational and work settings. There is no other area of psychology in which a closer correspondence between application and science exists. It covers many topics ranging from methods of hiring employees to theories of how organizations work. It is concerned with helping organizations get the most from their employees or human resources as well as which organizations take care of employee health and well-being”.

As all students of the social sciences soon discover, definitions are of limited use, although they do highlight slightly different emphases between both writers and the disciplines they rely on most heavily. Certainly, there appears to be no shared and parsimonious definition of work psychology (or for that matter industrial and organizational psychology, or management science). Disciplines change and develop and encompass a very wide range of issues. However, the following may be proposed as a definition of organizational psychology:

Organizational psychology is the study of how individuals are recruited, selected and socialized into organizations; how they are rewarded and motivated; how organizations are structured formally and informally into groups, sections and teams; and how leaders emerge and behave. It also examines how the organization influences the thoughts, feelings and behaviour of all employees by the actual, imagined or implied behaviour of others in their organization. Organizational psychology is the study of the individual in the organization, but it is also concerned with small and large groups and the organization as a whole as it impacts on the individual. Organizational psychology is a relatively young science. Like cognitive science, it is a hybrid discipline that is happy to break down disciplinary boundaries. From a psychological perspective, the major branches of the discipline to have influenced organizational psychology are experimental, differential, engineering and social psychology.

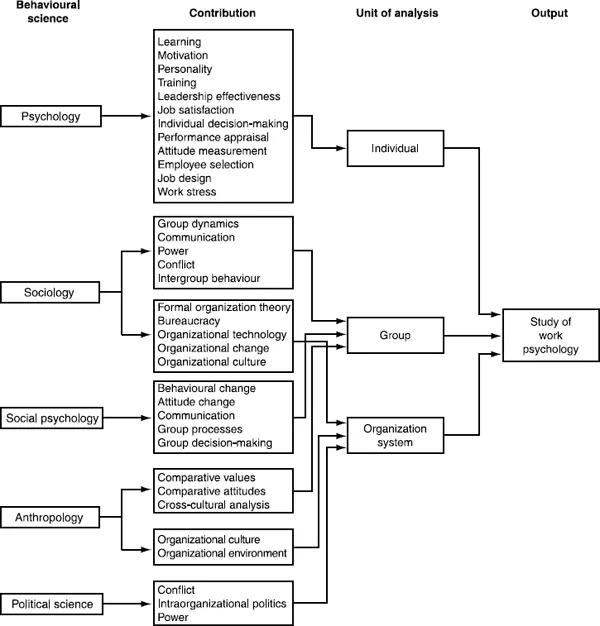

Another common way to understand work psychology is to look at its behavioural science founder disciplines, their contributions and special units of analysis. It is agreed that, of necessity, the subject of work psychology must be multidisciplinary. Psychology needs to take into consideration sociological factors; economics must take into consideration the foibles and idiosyncrasies so often researched by psychologists. So, work psychology is a hybrid that has borrowed (or stolen) ideas, concepts, methods and insights from some of the most established – subjects, particularly economics, psychology and sociology.

Figure 1.1 (based on Robbins, 1991: p. 14) illustrates the major contributory behavioural sciences. Four important points need to be made:

Figure 1.1 Towards a work psychology discipline. Adapted from Robbins (1991). Reproduced with the permission of Prentice-Hall, Inc.

• First, a good case could be made for including other disciplines, such as social administration/policy, industrial relations, international relations and computer science, although many of these are themselves hybrids.

• Secondly, the list of contributions in the second column are highly debatable – what is included and what not. Certainly, different writers would come up with different lists.

• Thirdly, the third column is very instructive; indeed, many textbooks are organized around the unit of analysis: the individual (intra- and interpersonal factors), the group (intra- and intergroup factors) and the organization (again inter- and intra-). Note that only psychology focuses on the individual, although branches of psychology focus not on “whole-person” research but some specific process such as memory or perception.

• Fourthly, this figure is too neat and it neglects to mention that various clashes or differences occur. Social psychologists and sociologists often study the same thing, but with different methods and assumptions. Economists and political scientists come to blows over ideology and epistemology. There is no neat slicing up of the cake of the natural phenomena of work psychology “carving-nature-at-her-joints”. It is messier and more unhappy than suggested above. Academic disciplines have competing mutually exclusive theories and, rather than favouring eclecticism, prefer exclusivity.

However, what is important to remember is that many academic disciplines continue to contribute to the development of work psychology. This is because of the very large number of issues and problems that are traditionally covered by work psychology.

A third way of describing the field of work psychology is to list the various components or separate subfields covered by work psychology specialists. Thus, Muchinsky (1983) listed six different subspecialities in an attempt at conceptual clarification:

• Personnel psychology examines the important role of individual differences in selecting and placing employees, in appraising the level of employees’ work performance, and in training recently hired, as well as veteran, employees to improve various aspects of their job-related behaviour.

• Organizational behaviour studies the impact of group and other social influences on role-related behaviours, on personal feelings of motivation and commitment, and on communication within the organizational setting.

• Organizational development concerns planned changes within organizations that can involve people, work procedures, job design and technology, and the structure of organizational relationships.

• Industrial relations concerns the interactions between and among employees and employers, and often involves organized labour unions.

• Vocational and career counselling examines the nature of rewarding and satisfying career paths in the context of individuals’ different patterns of interests and abilities.

• Engineering psychology generally focuses on the design of tools, equipment and work environments with an eye towards maximizing the effectiveness of women and men as they operate in human–machine systems.

Lowenberg and Conrad (1998) suggest five slightly different areas based on a survey of working American psychologists. They are organizational development and change (examining structure and roles and their impact on productivity and satisfaction); individual development (mentoring, stress management, counselling); performance evaluation and selection (developing assessment tools for selection, placement, classification and promotion); preparing and presenting results (including research activities); and compensation and benefits (developing criteria, measuring utility and evaluating the level of accomplishment.

By giving one an idea of the specialities within work psychology, rather than the disciplines that contribute to it, it becomes easier to understand the range of issues dealt with by organizational psychologists.

Another way to discover the range of the disciplines is to examine the common topics covered on courses. The following is typical of the course topics covered in work psychology programmes (Dipboye, Smith, & Howell, 1994):

History and systems of psychology

Fields of psychology

Work motivation theory

Vocational choice

Organizational development

Attitude measurement and theory

Psychometrics

Decision theory

Human performance/human factors

Consumer behaviour

Measurement of personality and individual differences

Small group processes

Performance appraisal and fe...