![]()

Chapter 1

The Temper of the Times

In the foreword to his masterpiece The Magic Mountain (1924) Thomas Mann wrote that the novel took place in the ‘old days, in the world before the Great War at the beginning of which so much began that has not yet begun to cease to begin’. This was the great catastrophe, which contemporaries viewed with the horrified perplexity of primitive man faced with a volcanic eruption. It was an event as significant as the French Revolution, but it was also a cataclysm that defied explanation. The British/German novelist Ford Madox Ford bemoaned the fact that history once held all the answers, but now was totally incapable of tackling the problem of the war. Walter Benjamin’s angel of history looked back in horror at a brutal past as it was dragged backwards into the future. The Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset wrote that ‘history is being turned upside down and a new reality is being created’. The publicist and historian Oswald Spengler announced that ‘optimism is cowardice’. The Austrian writer Egon Friedell proclaimed that history did not exist, although that did not stop him writing numerous works on the subject. Sellar and Yeatman in 1066 and All That light-heartedly suggested that history was simply what one remembered. After 11 November 1918 there was a great deal to be remembered.

There was nothing new in this pessimism. It dated back to Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, to Burckhardt and Houston Stewart Chamberlain to name but a few, and the war seemed a cruel vindication of their gloom. In a world without meaning where, as Siegfried Kracauer argued, reality was a mere construction, the temptation to aestheticise violence was hard to resist. Ernst Jünger, Ernst von Salomon, Emilio Marinetti and Gabriele D’Annunzio saw violence as a transcendental quality that existed well beyond the realms of morality, history or rationality. This attitude was reflected in a militarisation of a society dominated by paramilitary groups such as the Freikorps, Fascists and Nazis, by Bolshevik thugs, nihilists and anarchists. It was a world fascinated by bandits and criminals, by outsiders and gratuitous acts of violence. Politics became militarised, whether it was in black-shirted Italy, brown-shirted Germany, the Austria of the Heimwehr, or the ‘Comrade Mauser’ socialism of the Soviet Union. The victorious powers were mercifully immune to this violence, but were left dangerously feeble when threatened by renewed conflict. The vast majority of the millions of French veterans were convinced pacifists. Britain mourned its dead and promised that such a tragedy should never again be allowed to happen. The United States withdrew from a Europe that had torn itself apart.

The self-confident certainties of nineteenth-century bourgeois liberalism had begun to crumble long before the end of the century, as a fierce debate raged over the problems of modernity. This was intensified after the horrific experience of a war that traumatised a generation, and proved so hard for memory to digest. The war had within it a certain democratic moment that led to a mobilisation and radicalisation of the masses, a phenomenon that both intrigued and horrified Ortega y Gasset, and which led him to prophesy the Spanish Civil War in The Revolt of the Masses (1929). Scholars debate whether or not World War I was a ‘total’ war, but whatever the answer there can be no doubt that the war touched almost everyone’s life. In Britain and France it was ‘The Great War’ and the ‘Grande Guerre’. In Germany it was a ‘World War’ (Weltkrieg) and as early as 1921 Charles Repington entitled his two-volume history of the war The First World War. The economic, social and political havoc it caused led Marcel Proust to speak of the ‘scum of universal fatuousness which the war left in its wake’, and to decry the ‘platitudinous fatuity’ of the elite in the face of a mounting crisis of which they only seemed to be dimly aware.

Was is still possible to believe in progress, or had society become so utterly decadent that it had become immune to the salutary and bracing effects of warfare? Did the war herald the beginning of a mass society in search of a sense of community and in need of strong and untrammelled leadership? Wartime debates over civilisation versus culture, the state and society, rights and obligations were hotly pursued and provided intoxicating material for radical ideologues. As the problems facing society became increasingly complex, the answers provided by the ‘terribles simplificateurs’ seemed irresistibly attractive. Where reason was left perplexed, faith could offer hope. Faith – no matter in what, obedience – no matter to whom, fight – regardless of the justice of one’s cause, became a magic remedy, as Mussolini was one of the first to realise. The politics of the Big Lie and the scapegoat provided simple solutions to immensely complicated problems. The need for a comforting illusion was so strong that some of the greatest minds of the day placed their extraordinary talents at the service of ignorance. As Gabriel Marcel argued, in a Godless world without any other form of transcendence it was all too easy to fall for the ‘idolatry of class’ or the ‘idolatry of race’.

Smug confidence that technological progress could provide solutions to the world’s major problems had been seriously undermined. The loss of the Titanic on its much-publicised maiden voyage in 1912 was a serious blow to British self-confidence, but it also served as a warning against the presumptions of technology. There was a further portent in 1930 when the huge airship R101 crashed, also on its maiden voyage. Above all it was the industrialised slaughter of the war that gave force to Nietzsche’s question whether mankind could make the ‘solidified intelligence’ of technology serve rational ends, or would mankind be destroyed by the power of its own invention.

Regardless of such misgivings a technological approach was applied to all aspects of society in the belief that thereby effective answers could be found to all its problems. Henry Ford and Frederick W. Taylor’s vision of a brave new world subject to the logic of technology was enthusiastically emulated not only in the capitalist West, but also in Lenin’s Russia. Society could be rationally planned and ordered, so as to be more efficient and to provide all that was necessary for a better life. Architects and planners set about designing an environment that was responsive to human needs. Eugenicists sought to improve the gene pool, by demanding the sterilisation of all those deemed to be carriers of genetically determined diseases or undesirable behaviour. In short, rational intelligence could provide all the answers, even to a devastated Europe in a state of turmoil.

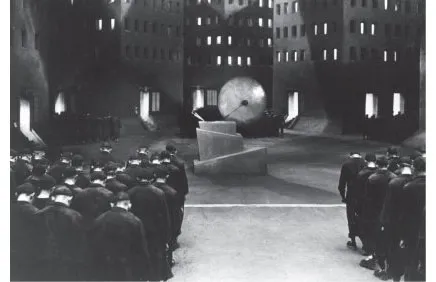

The great depression was the technocrats’ ‘Titanic’ and the reverse side of the modern, in the shape of mass unemployment, alienation and anomie, political crisis and revolt. There had always been a sense of deep uneasiness at the heart of the modernist discourse. Walter Rathenau, the most admirable of the Weimar republicans, expressed his deep unease about the cold and rational technological world, which he as a leading industrialist did so much to shape. Schopenhauer’s pessimism, transmitted via Kierkegaard’s morbid meditations on mass society and Nietzsche’s intoxicating denial of the concept of objective truth, was used as ammunition against the notion of progress. ‘Progress’ was no longer viewed as improvement but rather as a process of self-destruction. Human beings were reduced to anonymous cogs in a vast machine as in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times or in the writings of Ernst Toller and Ernst Niekisch. Spengler claimed that civilisation itself had become a machine that was destroying humanity. W.H. Auden and Gottfried Benn saw modern man as an Icarus doomed to be destroyed by his own ingenuity. Civilisation was reduced to T.S. Eliot’s Waste Land, where ‘I think we are in rats’ alley/Where the dead men lost their bones’, and the question was ‘What shall we do tomorrow?/What shall we ever do?’ Such sentiments are echoed in the pathetic ordinariness of his J. Alfred Prufrock who said ‘I should have been a pair of ragged laws/Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.’ Louis MacNeice succumbed to a bitter scepticism in his ‘Bagpipe Music’: ‘The glass is falling hour by hour, the glass will fall for ever,/ But if you break the bloody glass you won’t hold up the weather.’ D.H. Lawrence sought salvation in the dark and irrational forces of nature. Georges Duhamel’s protagonist Salavin struggled against existential ennui, and bitterly bemoaned his inconsolability as he searched for transcendence in a world without God. He was to provide a model for Sartre and Camus and the post-war existentialists. The city was no longer the stimulating and exciting locus of the modern; it was now an ‘asphalt jungle’ and a ‘moloch’, the brutal environment of Alfred Döblin’s novel Berlin Alexanderplatz. For many ‘America’ stood for all that was reprehensible about the modern world.

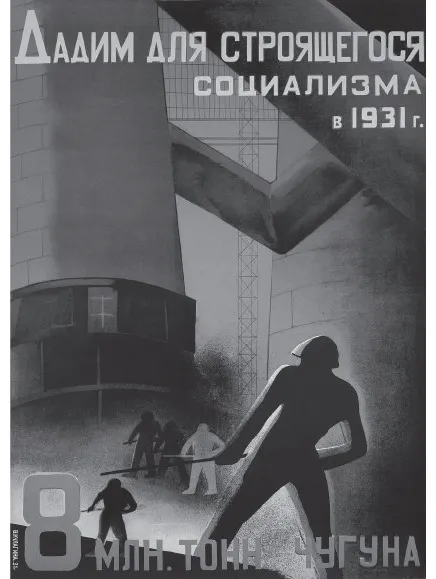

The heroic masses: Soviet poster of 1931 – ‘We will produce 8 million tons of pig iron in order to build socialism’

The downtrodden masses: scene from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis

Ferdinand Tönnies had wrestled with these ideas and in 1887 had made the clear distinction between ‘society’ (Gesellschaft ) and ‘community’ (Gemeinschaft ). ‘Society’ was the cold, artificial, bloodless world of the city and the marketplace. ‘Community’ the organic, traditional, emotional and harmonious life of village and countryside. In Tönnies’ pessimistic vision society would eventually swallow up and destroy community and destroy the people (Volk).

Ortega y Gasset, the most popular of the critics of mass society, in The Revolt of the Masses (1929) bemoaned the levelling down and standardisation of thought, taste and material culture; of income, education, gender and sex that threatened the foundations of a civilisation which was based on a clear distinction between an elite and the masses. The masses were the intolerant and violent advocates of direct action, as in Italian fascism and Spanish anarchosyndicalism. At the root of the problem for Ortega was the blind belief that the staggering achievements of technology and the extraordinary improvements in living standards were somehow natural, preordained and selfevident. The technologists, the engineers and doctors were among the worst offenders. They were the ‘sabio-ignorante’ (learned ignoramuses) who, all too aware of their competence in their own specialised fields, failed to understand that it was technology that was turning people into barbarians. He rejected both the US and the Soviet models, and felt that Europe’s only hope lay in a rejection of the dictators and of the nation state, to be replaced by a united Europe with firmly entrenched and genuinely liberal principals. He had now arrived at a position very close to that of the amiable Austrian pan-Europeanist, Count Richard Coudenhouve-Kalergi, who although a passionate opponent of totalitarianism felt that democracy was little more than a poor substitute for a genuine aristocracy.

There was widespread agreement among intellectuals, of whatever political colouring, with Ortega’s contention that civilisation’s progress resulted in a cultural retreat and a loss of cultural vitality. Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Walter Benjamin, Georges Sorel, Sigmund Freud, Paul Valéry and Hermann Hesse joined the choir to sing a complex polyphonic lamentation over the ghastliness of the modern world that was peppered with words such as ‘anomie’, ‘transcendental homelessness’, ‘ambivalence’ and ‘rootlessness’. Max Weber called for the ‘re-enchantment’ of the world, Georg Simmel asked what made society possible and called for the salvation of the totality of human existence from the pitiless reality of the world, salvation from the fragmentary and a restoration of integrality. In his Autumn Journal Louis MacNeice bemoaned the fact that: ‘. . . It is hard to imagine/A world where the many would have their chance without/A fall in the standard of intellectual living/And nothing that the highbrow cared about.’ Meanwhile the prophets of doom echoed Trollope’s Mr Turnbull with their predictions of evil consequences, while at the same time doing their best to bring about the verification of their own prophecies.

Karl Jaspers wrestled with these problems in The Intellectual Problems of the Age (Die Geistige Probleme der Zeit, 1931), which, with The Revolt of the Masses, was one of the most widely read and influential books in the inter-war period. For Jaspers this was a period not only of political, economic and social crisis, but first and foremost of a deep-rooted intellectual malaise. Mankind’s knowledge and ability had become so vast and was so ever expanding that there were no longer any generally accepted and binding transcendental values, leaving control in the hands of anonymous experts and bureaucrats. Ration-ality was applied almost exclusively to practical problems, leaving ample room for the irrational, as in the racial hocus-pocus, the glorification of violence and the restless vitality of National Socialism. The crisis was generally accepted as an unavoidable destiny from which there was no escape, and mankind stood passive and helpless before the antinomies of the individual and the collective, body and soul, being and existence. This situation for Jaspers, far for being grounds for nihilism and pessimism, offered a wide freedom of choice. There were no easy answers, but the individual struggle for elucidation could lead to the solution of immediate problems. He sought thereby to preserve the philosophical tradition of the ancients and Judeo-Christian values against the assault of the barbarians. His tragic-heroic stand against the forces of the irrational found considerable resonance, particularly among students, and his short book went through a number of editions.

Jaspers was building on arguments presented by Max Weber in a remarkable lecture he gave in 1919 in Munich, amid the ruins of the German Empire and of a curious socialist revolution. He took up the question posed by Tolstoy that science, for all its miracles and triumphs, for all the fundamental changes it had made in our lives, and with its immense destructive powers which had been so brutally manifest in the war, was unable to answer the fundamental questions: How should we live? What should we do? To Weber, far from this being a fundamental and insoluble ambivalence at the heart of modernity, this offered a great chance. Science left us the freedom to make such choices independently from objective scientific laws, and he issued a timely and timeless warning against faiths masquerading as scientific truths. Such notions as scientific socialism and Nazi biologism were for Weber examples of political passions dressed up as historical necessity. Weber pleaded for a ‘rational individuality’ that could find a way between the dangers of an impersonal and purely functional rationality and a passionate romantic irrationalism.

Traditional values and certainties were crumbling in a world that was becoming increasingly pluralistic, differentiated and individualistic, which obeyed the dictates of the markeplace and the logic of productive forces. The old liberal belief that there need be no fundamental dichotomy between the pursuit of individual interests and a sense of moral obligation towards the community, and that the world was marching resolutely towards a desirable consummation, became increasingly hard to sustain. Progress, particularly in its socialist guise, seemed to be leading to what Ortega called a ‘rebarbarianisation’. Marxists took delight in all this, for was it not the outward sign of a bourgeois-capitalist society in the throes of its final collapse?

Many of those who regarded the fruits of enlightenment and progress with profound pessimism felt that only the will, irrationality and faith offered a way out. Henri Bergson won many followers, and a Nobel Prize in 1927, for his insistence that philosophy provided the answer to the restraints of the scientific and the everyday, by setting the imagination free and relying on intuitive subjectivity.

Some, like the anarcho-syndicalist Georges Sorel and the Italian futurist Marinetti, swallowed a heavy dose of Nietzsche and managed to convince themselves that the war provided a purifying experience, an alternative to the non-committal essence of the modern, and an opportunity to restore order to the world. They turned their backs on the feeble and slavish morality of the Judeo-Christian tradition, and heralded the mystical experience of a tightly knit community of supermen, whether of Ernst Jünger’s frontline soldiers, Sorel’s striking workers, d’Annuzio’s paramilitary troops, the anti-Semitic, blood-and-soil regionalism of Maurice Barrès, or the close circle of precious young men around the poet Stefan George. The call was for ‘action’, ‘revolution’, ‘struggle’ or ‘deeds’. Carl Schmitt, with his characteristic bluntness, announced that this was a state of emergency for which the only solution was the ‘expulsion or destruction of the heterogenous’. This cannot be dismissed as the vaguely ridiculous attitudinising of an unworldly academic. It was symptomatic of a profound malaise that was to have truly frightful consequences.

Few thinkers reflected the problems and uncertainties of contemporary life more accurately and profoundly than Martin Heidegger. In spite of its painfully convoluted and hermetic language, his major work of the period Being and Time (1927) bears a remarkable resemblance to the novels of his contemporary, Franz Kafka, although Heidegger sadly lacked the latter’s often overlooked and mordant sense of humour. Heidegger had served on the Western Front in a meteorological unit charged with making calculations for the use of gas during the 1918 offensive in the Champagne. He was profoundly affected by this experience, which for him stripped everything away down to the basic core of the personality. That the individual was now forced to rely entirely on the self, without any of the material and spiritual comforts of civilisation, he regarded as a valuable opportunity.

Heidegger set about stripping philosophy down to the basic problem of being, a process that he described as ‘destruction’. He had been obliged to leave the Jesuit order because of health problems in 1909, and ceased to study for the priesthood in 1911. By 1919, after much heart-searching, he reluctantly came to agree with Nietzsche that God was indeed dead. Having ‘destroyed’ theology he set about the destruction of his mentor Husserl’s phenomenology. Finally he set to work on the Western tradition of philosophy and metaphysics, which he felt had trapped thinkers since Plato in a secondhand and shop-worn set of abstractions that had become autonomous, and which provided little more than ‘useless’ knowledge of the essence of things. He called for a fundamental rethinking of philosophy starting with the pre-Socratics, above all Heraclitus, the ‘weeping philosopher’ and the ‘dark one’, whose profound pessimism and extreme obscurity he found particularly appealing and worthy of emulation.

The German crisis of the spirit, with which thinkers as different as the historian Oswald Spengler or the theologian Karl Barth wrestled, was reflected in an extreme fashion in Heidegger’s work. He agreed with ‘conservative revolutionaries’ such as Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt, Moeller van den Bruck and Ernst Niekisch that Western civilisation had degenerated into an ‘exhausted pseudo-cultu...