PREHISTORY AND THE INDUS CIVILISATION

When the great cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro were discovered in the 1920s the history of the Indian subcontinent attained a new dimension. The discovery of these centres of the early Indus civilisation was a major achievement of archaeology. Before these centres were known, the Indo-Aryans were regarded as the creators of the first early culture of the subcontinent. They were supposed to have come down to the Indian plains in the second millennium BC. But the great cities of the Indus civilisation proved to be much older, reaching back into the third and fourth millennia. After ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, this Indus civilisation emerged as the third major early civilisation of mankind, followed about a millennium later by China.

Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro show a surprising similarity although they were separated by about 350 miles. In each city the archaeologists found an acropolis and a lower city, each fortified separately. The acropolis, situated to the west of each city and raised on an artificial mound made of bricks, contained large assembly halls and edifices which were obviously constructed for religious cults. In Mohenjo-Daro there was a ‘Great Bath’ (39 by 23 feet, with a depth of 8 feet) at the centre of the acropolis which may have been used for ritual purposes. This bath was connected to an elaborate water supply system and sewers. To the east of this bath there was a big building (about 230 by 78 feet) which is thought to have been a palace either of a king or of a high priest.

A special feature of each of these cities was the large platforms which have been interpreted by the excavators as the foundations of granaries. In Mohenjo-Daro it was situated in the acropolis; in Harappa it was immediately adjacent to it. In Mohenjo-Daro this architectural complex, constructed next to the Great Bath, is still particularly impressive. Its foundation, running east to west, was 150 feet long and 75 feet wide. On this foundation were twenty-seven compartments in three rows. The 15-foot walls of these are still extant. These compartments were very well ventilated and, in cases where they were used as granaries, they could have been filled from outside the acropolis. At Harappa there were some small houses, assumed to be those of workers or slaves, and a large open space between the acropolis and these buildings.

The big lower cities were divided into rectangular areas. In Mohenjo-Daro there were nine such areas, each about 1,200 by 800 feet. Broad main streets, about 30 feet wide, separated these parts of the city from each other. All the houses were connected directly to the excellent sewage system which ran through all the numerous small alleys. Many houses had a spacious interior courtyard and private wells. All houses were built with standardised bricks. The width of each brick was twice as much as its height and its length twice as large as its width.

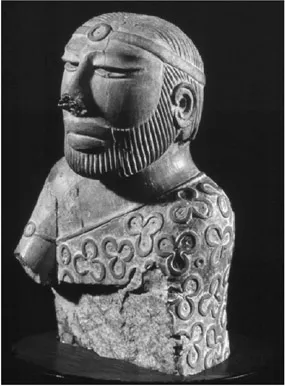

But it was not only this excellent city planning which impressed the archaeologists, they also found some interesting sculptures and thousands of well-carved seals made of steatite. These seals show many figures and symbols of the religious life of the people of this early culture. There are tree deities among them and there is the famous so-called ‘Proto-Shiva’ who is seated in the typical pose of a meditating man. He has three heads, an erect phallus and is surrounded by animals which were also worshipped by the Hindus of a later age. These seals also show evidence of a script which has not yet been deciphered.

1.1 Aerial view of the acropolis of Mohenjo-Daro; the ‘Great Bath’ at its centre.

Both cities shared a uniform system of weights and measures based on binary numbers and the decimal system. Articles made of copper and ornaments with precious stones show that there was a flourishing international trade. More evidence for this international trade emerged when seals of the Indus culture were found in Mesopotamia and other seals which could be traced to Mesopotamia were discovered in the cities on the Indus.

1.2 Mohenjo-Daro, the so-called, ‘Priest King’, late third millenium BC

Before indigenous sites of earlier stages of the Indus civilisation were excavated it was believed that Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro were merely outposts of the Mesopotamian civilisation, either constructed by migrants or at least designed according to their spec-ifications. These speculations were strengthened by the mention in Mesopotamian sources of countries such as Dilmun, Magan and Meluhha. Dilmun has been identified as Bahrain and Magan seems to be identical with present Oman. Meluhha may have referred to the Indus valley from where Mesopotamia obtained wood, copper, gold, silver, carnelian and cotton.

In analogy to the Mesopotamian precedent, the Indus culture was thought to be based on a theocratic state whose twin capitals Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro obviously showed the traces of a highly centralised organisation. Scholars were also fairly sure of the reasons for the sudden decline of these cities since scattered skeletons which showed traces of violent death were found in the uppermost strata of Mohenjo-Daro. It appeared that men, women and children had been exterminated by conquerors in a ‘last massacre’. The conquerors were assumed to be the Aryans who invaded India around the middle of the second millennium BC. Their warrior god, Indra, was, after all, praised as a breaker of forts in many Vedic hymns.

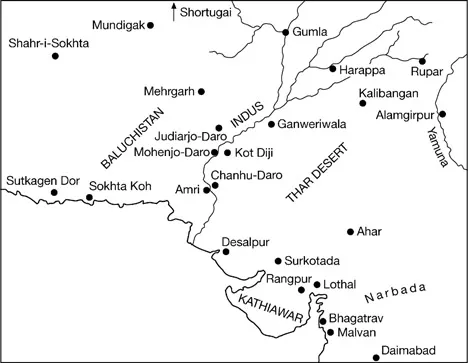

However, after the Second World War, intensive archaeological research in Afghanistan, Pakistan and India greatly enhanced our knowledge of the historical evolution and the spatial extension of the Indus civilisation (see Map 1.1). Earlier assessments of the rise and fall of this civilisation had to be revised. The new excavations showed that this civilisation, at its height early in the late third millennium BC, had encompassed an area larger than Western Europe.

In the Indus valley, other important cities of this civilisation, such as Kot Diji to the east of Mohenjo-Daro and Amri in the Dadu District on the lower Indus, were discovered in the years after 1958. In Kathiawar and on the coast of Gujarat similar centres were traced. Thus in 1954 Lothal was excavated south of Ahmadabad. It is claimed that Lothal was a major port of this period. Another 100 miles further south Malwan was also identified in 1967 as a site of the Indus civilisation. It is located close to Surat and so far marks, together with Daimabad in the Ahmadnagar District of Maharashtra, the southernmost extension of this culture. The spread of the Indus civilisation to the east was documented by the 1961 excavations at Kalibangan in Rajasthan about 200 miles west of Delhi. However, Alamgirpur, in Meerut District in the centre of the Ganga–Yamuna Doab, is considered to mark the farthest extension to the east of this culture. In the north, Rupar in the foothills of the Himalayas is the farthest outpost which is known in India. In the west, traces of this civilisation were found in Baluchistan close to the border of present Iran at Sutkagen Dor. This was probably a trading centre on the route connecting the Indus valley with Mesopotamia. Afghanistan also has its share of Indus civilisation sites. This country was known for its lapis lazuli which was coveted everywhere even in those early times. At Mundigak near Kandahar a palace was excavated which has an impressive façade decorated with pillars. This site, probably one of the earliest settlements in the entire region, is thought to be an outpost of the Indus civilisation. Another one was found more recently further to the north at Shortugai on the Amu Darya.

This amazing extension of our knowledge about the spatial spread of the Indus civilisation was accompanied by an equally successful exploration of its history. Earlier strata of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa as well as of Kali-bangan, Amri and Kot Diji were excavated in a second round of archaeological research. In this way a continuous sequence of strata, showing the gradual development to the high standard of the full-fledged Indus civilisation, was established. These strata have been named Pre-Harappan, Early Harappan, Mature Harappan and Late Harappan. The most important result of this research is the clear proof of the long-term indigenous evolution of this civilisation which obviously began on the periphery of the Indus valley in the hills of eastern Baluchistan and then extended into the plains. There were certainly connections with Mesopotamia, but the earlier hypothesis that the Indus civilisation was merely an extension of Mesopotamian civilisation had to be rejected.

The anatomy of four sites

The various stages of the indigenous evolution of the Indus civilisation can be documented by an analysis of four sites which have been excavated in more recent years: Mehrgarh, Amri, Kalibangan, Lothal. These four sites reflect the sequence of the four important phases in the protohistory of the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent. The sequence begins with the transition of nomadic herdsmen to settled agriculturists in eastern Baluchistan, continues with the growth of large villages in the Indus valley and the rise of towns, leads to the emergence of the great cities and, finally, ends with their decline. The first stage is exemplified by Mehrgarh in Baluchistan, the second by Amri in the southern Indus valley and the third and fourth by Kali-bangan in Rajasthan and by Lothal in Gujarat.

Mehrgarh

Mehrgarh is situated about 150 miles to the northwest of Mohenjo-Daro at the foot of the Bolan Pass, which links the Indus valley via Quetta and Kandahar with the Iranian plateau. The site, excavated by French archaeologists since 1974, is about 1,000 yards in diameter and contains seven excavation sites with different strata of early settlements. The oldest mound shows in its upper strata a large Neolithic village which, according to radio-carbon dating, belongs to the sixth millennium BC. The rectangular houses were made of adobe bricks, but ceramics were obviously still unknown to the inhabitants. The most important finds were traces of grain and innumerable flint blades which appear to have been used as sickles for cutting the grain. These clearly establish that some kind of cultivation prevailed in Baluchistan even at that early age. Several types of grain were identified: two kinds of barley, and wheat, particularly emmer. Surprisingly, the same types of grain were found in even lower strata going back to the seventh millennium.

The early transition from hunting and nomadic life to settled agriculture and animal husbandry is documented also by large numbers of animal bones which were found in various Neolithic strata of the site. The oldest strata of the seventh millennium contained mostly remnants of wild animals such as antelopes, wild goats and wild sheep. But in later strata the bones of domesticated animals such as goats, sheep and cows were much more numerous. The domestication of animals must have begun in Baluchistan at about the same time as in western Asia. Sheep were the first animals to be tamed, followed by water buffaloes whose earliest remains, outside China, were discovered here.

Precious items found in the graves of Mehrgarh provide evidence for the existence of a network of long-distance trade even during this early period. There were beads made of turquoise from Persia or central Asia, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan and shells which must have come from the coast 400 miles away.

Next to this oldest mound at Mehrgarh there is another site which contains Chalcolithic settlements showing the transition from the Stone Age to the Bronze Age. Ceramics as well as a copper ring and a copper bead were found here. The rise of handicraft is clearly in evidence at this stage. Hundreds of bone awls were found, as well as stones which seem to have been used for sharpening these awls. The uppermost layer of this site contains shards of painted ceramics very similar to those found in a settlement of the fourth millennium (Kili Ghul Mohammad III) near Quetta. When this stage was reached at Mehrgarh the settlement moved a few hundred yards from the older ones. The continuity is documented by finds of the same type of ceramics which characterised the final stage of the second settlement.

In this third phase in the fifth and early fourth millennia skills were obviously much improved and the potter’s wheel was introduced to manufacture large amounts of fine ceramics. In this period Mehrgarh seems to have given rise to a technical innovation by introducing a drill moved by means of a bow. The drill was made of green jasper and was used to drill holes into beads made of lapis lazuli, turquoise and carnelian. Similar drills were found at Shahr-i-Sokhta in eastern Iran and at Chanhu-Daro in the Indus valley, but these drills belong to a period which is about one millennium later. Another find at Mehrgarh was that of parts of a crucible for the melting of copper.

At about 3500 BC, the settlement was shifted once more. In this fourth phase ceramics attained major importance. The potters produced large storage jars decorated with geometric patterns as well as smaller receptacles for daily use. Some of the shards are only as thick as an eggshell. Small female figurines made of terracotta were found here and terracotta seals, the earliest precursors of the seals found in the Indus valley, were also found. Mehrgarh must have been inhabited by that time by a well-settled and fairly wealthy population.

The fifth phase of settlement at Mehrgarh started around 3200 BC. The features characteristic of this phase had also been noted in sites in eastern Iran and central Asia. Because not much was known about Baluchistan’s protohistory prior to the fourth millennium BC, these features were thought to have derived from those western regions. But the excavations at Mehrgarh show that the early settlers of Baluchistan were not just passive imitators but had actively contributed to the cultural evolution. Long-distance trade certainly contributed to the exchange of cultural achievements in this early period.

The subsequent phases of settlement at Mehrgarh, from about 3000 to 2500 BC and immediately preceding the emergence of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, show increasing wealth and urbanisation. A new type of seal with animal symbols, and terracotta figurines of men and women with elaborately dressed hair, seem to reflect a new life style. Artefacts such as the realistic sculpture of a man’s head and small, delicately designed figurines fore-shadow the later style of Harappan art. The topmost strata of settlements in Mehrgarh are crowded with two-storey buildings. Firewood seems to have been scarce in this final period as cow dung was used for fuel, as it still is. Ceramics were produced on suc...