![]()

I

BASICS OF FOOD MICROBIOLOGY

1 The Trajectory of Food Microbiology

2 Microbial Growth, Survival, and Death in Foods

3 Spores and Their Significance

4 Detection and Enumeration of Microbes in Food

5 Rapid and Automated Microbial Methods

6 Indicator Microorganisms and Microbiological Criteria

![]()

| | 1 | The Trajectory of Food Microbiology |

Learning Objectives

The information in this chapter will help the student:

- increase awareness of the antiquity of microbial life and the newness of food microbiology as a scientific field

- appreciate how fundamental discoveries in microbiology still influence the practice of food microbiology

- understand the origins of food microbiology and thus anticipate its forward path

Introduction

Who’s on First?

Food Microbiology, Past and Present

To the Future and Beyond

Summary

Suggested reading

Questions for critical thought

INTRODUCTION

A former president of the American Society for Microbiology (Box 1.1) defined microbiology as an artificial subdiscipline of biology based on size. This suggests that basic biological principles hold true, and are often discovered, in the field of microbiology. Food microbiology is a further subdivision of microbiology. It studies microbes that grow in food and how food environments influence microbes. In some ways, food microbiology has changed radically in the last 20 years. The number of recognized foodborne pathogens has doubled. “Safety through end product testing” has given way to “safety by design” provided by Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP). In the United States, the Food Safety Modernization Act introduced Hazard Analysis Risk-Based Preventative Controls. Genetic and immunological probes have replaced biochemical tests and reduced testing time from days to minutes. In other ways, food microbiology is still near the beginning. Louis Pasteur would find his pipettes in a modern laboratory. Julius Richard Petri would find his plates (albeit plastic rather than glass). Hans Christian Gram would find all the reagents required for his stain. Food microbiologists still study only the microbes that we can see under the microscope and grow on agar media in petri dishes. Experts suggest that only 1% of all the bacteria in the biosphere can be detected by cultural methods.

Box 1.1

Preparing for the future

Membership in professional societies is a great way to advance professionally, even as a student (who benefits from reduced membership fees and is eligible for a variety of scholarships). Professional societies provide continuing-education and employment services to their members, provide expertise to those making laws and public policies, have annual meetings for presentation of the latest science, and publish books and journals. The three main societies for food microbiologists are listed below. Applications for membership can be obtained from their websites.

The American Society for Microbiology (ASM) (http://www.asm.org) is the largest life science society in the world. It has 27 divisions covering all facets of microbiology from microbial pathogenesis to immunology to antimicrobial agents to food microbiology, and it publishes 12 scholarly journals. ASM Press is the publisher of this book.

The Institute of Food Technologists (IFT) (http://www.ift.org) devotes itself to all areas of food science by discipline (food microbiology, food chemistry, and food engineering), as well as by commodity (cereals, fruits and vegetables, and seafood) and by processing (refrigerated foods). The IFT is a nonprofit scientific society with over 17,000 members working in food science, food technology, and related professions in industry, academia, and government. The IFT publishes four journals, sponsors a variety of short courses, and contributes to public policy and opinion at national, state, and local levels.

The International Association for Food Protection (IAFP) (http://www.foodprotection.org) is the only professional society devoted exclusively to food safety microbiology. IAFP is dedicated to the education and service of its members, as well as industry personnel. Members keep informed of the latest scientific, technical, and practical developments in food safety and sanitation. IAFP publishes two scientific journals, Food Protection Trends and Journal of Food Protection.

This chapter’s discussion of microbes per se sets the stage for a historical review of food microbiology. The bulk of the discussion concerns bacteria. Most of this book deals with bacteria. Viruses and prions are covered later in a single chapter because so little is known about them. This chapter ends with some thoughts about future developments in the field.

WHO’S ON FIRST?

Let there be no doubt about it: the microbes were here first. It is a microbial world (Fig. 1.1). If the earth came into being at 12:01 a.m. of a 24-h day, microbes would arrive at dawn and remain the only living things until well after dusk. Around 9 p.m., larger animals would emerge, and a few seconds before midnight, humans would appear. The microbes were here first, they cohabit the planet with us, and they will be here after humans are gone. Life is not sterile. Microbes can never be (nor should they be) conquered, once and for all. The food microbiologist can only create foods that microbes do not “like,” manipulate the growth of microbes that are in food, kill them, or exclude them by physical barriers.

Figure 1.1

It’s a microbial world.

Bacteria live in airless bogs, thermal vents, boiling geysers, us, and foods. We are lucky that they are here for microbes form the foundation of the biosphere. We could not exist without microbes, but they would do just fine without us. Photosynthetic bacteria fix carbon into usable forms and make much of our oxygen. Rhizobium bacteria fix air’s elemental nitrogen into ammonia that can be used for a variety of life processes. Degradative enzymes allow ruminants to digest cellulose. Microbes recycle the dead into basic components that can be used again and again. Microbes in our intestines aid in digestion, produce vitamins, and prevent colonization by pathogens. For the most part, microbes are our friends.

FOOD MICROBIOLOGY, PAST AND PRESENT

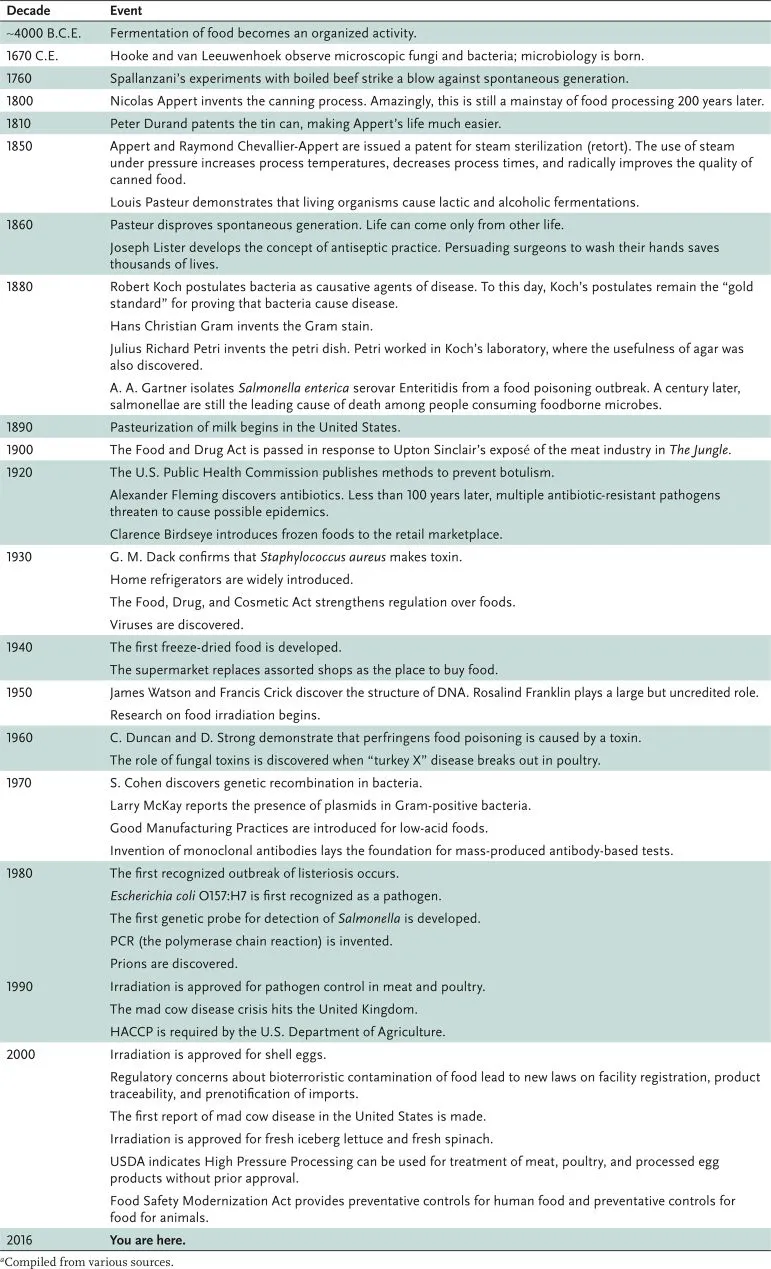

From the dawn of civilization until about 10,000 years ago, humans were hunter-gatherers. Humans were lucky to have enough. There was neither surplus nor a settled place to store it. Preservation was not an issue. With the shift to agricultural societies, storage, spoilage, and preservation became important challenges. The first preservation methods were undoubtedly accidental. Sun-dried, salted, or frozen foods did not spoil. In the classic “turning lemons into lemonade” style, early humans learned that “spoiled” milk could be acceptable or even desirable if viewed as “fermented.” Fermenting food became an organized activity around 4000 B.C.E. (Table 1.1). Breweries and bakeries sprang up long before the idea of yeast was conceived.

Table 1.1 Significant events in the history of food microbiologya

Humans remained ignorant of microbes for thousands of years. In 1665, Robert Hooke published Micrographia, the first illustrated book on microscopy that detailed the structure of Mucor, a microscopic fungus. In 1676, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (Fig. 1.2) used a crude microscope (Fig. 1.3) of Hooke’s design to see small living things in pond water. Microbiology was born!

Figure 1.2

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek.

Figure 1.3

Replica of van Leeuwenhoek microscope.

Nonetheless, it took another 200 year...