- 332 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dinosaurs of Darkness

About this book

"A valuable volume detailing an underexplored region of the world of dinosaurs . . . essential reading for any dino-devotee." —

ForeWord

Dinosaurs of Darkness opens a doorway to a fascinating former world, between 100 million and 120 million years ago, when Australia was far south of its present location and joined to Antarctica. Dinosaurs lived in this polar region.

How were the polar dinosaurs discovered? What do we now know about them? Thomas H. Rich and Patricia Vickers-Rich, who have played crucial roles in their discovery, describe how they and others collected the fossils indispensable to our knowledge of this realm and how painstaking laboratory work and analyses continue to unlock the secrets of the polar dinosaurs. This scientific adventure makes for a fascinating story: it begins with one destination in mind and ends at another, arrived at by a most roundabout route, down byways and back from dead ends. Dinosaurs of Darkness is a personal, absorbing account of the way scientific research is actually conducted and how hard—and rewarding—it is to mine the knowledge of this remarkable life of the past.

The award-winning first edition has now been thoroughly updated with the latest discoveries and interpretations, along with over 100 new photographs and charts, many in color.

Dinosaurs of Darkness opens a doorway to a fascinating former world, between 100 million and 120 million years ago, when Australia was far south of its present location and joined to Antarctica. Dinosaurs lived in this polar region.

How were the polar dinosaurs discovered? What do we now know about them? Thomas H. Rich and Patricia Vickers-Rich, who have played crucial roles in their discovery, describe how they and others collected the fossils indispensable to our knowledge of this realm and how painstaking laboratory work and analyses continue to unlock the secrets of the polar dinosaurs. This scientific adventure makes for a fascinating story: it begins with one destination in mind and ends at another, arrived at by a most roundabout route, down byways and back from dead ends. Dinosaurs of Darkness is a personal, absorbing account of the way scientific research is actually conducted and how hard—and rewarding—it is to mine the knowledge of this remarkable life of the past.

The award-winning first edition has now been thoroughly updated with the latest discoveries and interpretations, along with over 100 new photographs and charts, many in color.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dinosaurs of Darkness by Thomas H. Rich,Patricia Vickers-Rich in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Dinosaur Cove

“Collect butterflies.” After fifty days of tunneling for fossils in the fourth season at Dinosaur Cove, that was Tom’s heartfelt response to the question, “Well, what will you do if you give up searching for dinosaurs?”

In 1980, a small, then-unnamed cove facing the Southern Ocean in Australia’s southeast had yielded a few bits of fossil bone. Because of this discovery, the site was soon christened Dinosaur Cove. One hundred and six million years before, an ancient stream channel, whose soft sands and muds subsequently turned to stone, had flowed through the site.

Starting in 1984, digging in earnest for fossils at the Cove had slowly brought to light a modest collection that for the first time provided a glimpse of what the dinosaur fauna of southeastern Australia had been like one hundred and six million years prior. Until 1978, only one dinosaur bone had been found in all of the Australian state of Victoria and not a lot more elsewhere on the continent. This Victorian specimen was indeed the first dinosaur bone that had ever been found in Australia.

But after fifty days in the fourth year of digging at Dinosaur Cove, all known sources of dinosaurs from southeastern Australia seemed to have been totally and utterly exhausted. Future prospects of finding more seemed dim.

Background

The living mammals and birds of Australia are the most distinctive of those known on any continent. They are clearly a reflection of Australia’s isolation, and the ways in which these groups originated and then evolved on this continent have been a prime area of study and speculation for more than a century. On the basis of the fossil record known from other continents, mammals seem to have originated at about the same time as dinosaurs,1 approximately 204 million years ago. Birds are quite ancient as well, at least 150 million years old.

Primarily on the basis of their mode of reproduction, living mammals are divided into three groups: monotremes, marsupials, and placentals. Monotremes include the platypus and several species of echidnas, and all lay eggs. Marsupials are born at a very immature stage and immediately crawl to and fasten onto a nipple, which is often, but not always, located within a natural fold of skin or pouch. This embryonic neophyte remains there continuously for a period much longer than their short gestation period. Marsupials include kangaroos, wombats, koalas, and the American opossums. Members of the placentals are born at a more advanced stage than are marsupials. They include such animals as cows, dogs, rats, bats, whales, and us.

More than half the modern terrestrial native mammals of Australia are marsupials. Marsupials are far more diverse in Australia than on any other continent. This has long been explained by the hypothesis that marsupials reached Australia far earlier than placentals, about the end of the Mesozoic Era (the Age of Reptiles) or at the beginning of the Cenozoic Era (the Age of Mammals)—about 66 million years ago. The route of marsupials into Australia was presumably via Antarctica from South America, the continent with the second most diverse fauna of living marsupials (and a rich fossil history of them as well). At the time marsupials were thought to have arrived in Australia, these three continents lay much closer together. They had not yet been split asunder by the processes of plate tectonics, which subsequently carried Australia far north of Antarctica.

Bats seem to have reached Australia by 55 million years ago. No one has yet found the remains of a single fossil of an unquestioned terrestrial placental of middle Cenozoic age in Australia, a time for which the fossil record of land mammals there is reasonably good. About 5 million years ago, rodents reached Australia—the only terrestrial placentals to do so unassisted by humans. Unlike the marsupials, the rodents arrived in Australia from Asia via the Malay Archipelago.

With the discovery of a single tooth in southeastern Queensland near the town of Murgon in 1990, doubt was first cast on the idea that Australian mammalian history was the outcome of the fortuitous early arrival of the marsupials and long absence of placentals.2 The Murgon tooth belonged to an animal named Tingamarra porterorum, possibly a member of a placental ungulate group, the Condylarthra. Tingamarra porterorum is thought to be Early Eocene in age. The identification of the specimen as a placental has been challenged.3 One additional similar, although significantly larger, tooth has since been discovered at the Tingamarra site. This find, plus the discovery of jaws of other mammals at the Tingamarra locality, give us reason to expect that further work there will unearth specimens that may provide the evidence necessary to determine unequivocally whether T. porterorum was indeed a placental mammal.

The Beginning

Until the 1950s, the fossil record of mammals in Australia was almost totally restricted to the last 2.6 million years, only the last 1 percent of their history. This short record was sufficient to throw considerable light on the major episode of extinction of large mammals and birds that occurred in Australia during this period. This late extinction event was part of a worldwide phenomenon, for on most other landmasses, similar episodes of mass extinction occurred either during or after the most recent Ice Age. Prior to that event, however, the Australian fossil record of these groups was virtually unknown.

That gap in the first 99 percent of Australian mammal and bird history attracted Professor R. A. Stirton of the University of California, Berkeley, to Australia in 1953 in order to locate fossils sufficiently old to begin filling in the gap. With the help of the South Australian Museum and guided by a suggestion of Sir Douglas Mawson to search the country east of Lake Eyre, Stirton did find the first significant collection of terrestrial mammals and birds older than 2.6 million years.4

By the time Stirton died in 1966, the broad outline of the evolution of these two groups in Australia for the last 10 percent of their history was known. However, the first 90 percent still remained tantalizingly elusive.

How Did It Begin?

Some people’s interest in a particular topic begins imperceptibly. Others can pin down the moment when such an interest takes hold. Tom’s abiding interest in Mesozoic mammals, beasties that were totally unknown in Australia until 1984, can be dated almost to the hour. For Christmas 1953, he received a copy of the book All About Dinosaurs by Roy Chapman Andrews,5 who thirty years before had led the American Museum of Natural History expeditions into Mongolia. These famous expeditions turned up dinosaur eggs as well as a vast treasure trove of dinosaur skeletons. As Tom read Andrews’s book that afternoon in 1953, he learned that a person who studies fossils is a paleontologist, and he decided then and there to become one. The last chapter of the book is called “Death of the Dinosaurs.” Above the chapter title is an illustration showing two small, beady-eyed mammals eating dinosaur eggs. “Those,” he thought, “are the interesting animals, our ancestors when the dinosaurs were alive.” That idea captivated his imagination as no other ever has. He never stopped wanting to know more and more about this little-known phase of prehistory.

It was for this reason that the missing first 90 percent of the Australian mammal record tantalized Tom so much, for the Mesozoic Era is the period when the first two-thirds of mammalian prehistory occurred.

For her PhD dissertation, Pat had begun to study the fossil birds that “Stirt” had collected in Australia before his untimely death. Because of this interest, we eventually immigrated to Australia, arriving in 1973. It was not our first trip to the Antipodes, though. In 1971, we had been part of an American Museum of Natural History–South Australian Museum–Queensland Museum expedition led by Richard Tedford,6 a former student of Stirton, searching for fossil mammals and birds.

When Pat started work at Monash University and Tom became employed at the National Museum of Victoria (now Museums Victoria), our research program was directed toward throwing light on the earlier history of mammals and birds in Australia. The first step was to find sites where such fossils could be collected.

We began searching systematically for older sites, starting in the areas where Stirton and his colleagues had previously collected. We had considerable success collecting fossils from known sites as well as discovering new fossil localities. This refined somewhat the picture of Australian mammalian and avian evolution during the last 10 percent of their history. However, the desired older fossils simply could not be found.

1.1. Drawing from All About Dinosaurs.

The unstinting help of interested and thoroughly dedicated associates—be they colleagues, students, paid assistants, parents, or volunteers—was critical to the favorable results that we did have. Time and again, the volunteers were to play a vital role in our progress. One instance of this was the discovery of a fossil bone, which was to turn the direction of our research from birds and mammals to dinosaurs.

John Long and Tim Flannery are cousins, who as boys collected fossils from the beaches near Beaumaris, a seaside suburb of Melbourne, under the tutelage of longtime resident Colin Macrae. Their enthusiasm has carried them both to positions as prominent scientists and public figures. In 1978, after having assisted with our research program for a few years, they decided to work with geologist Rob Glenie to try to find more fossil bones where the one dinosaur fossil then known from Victoria had been collected at the turn of the 20th century.

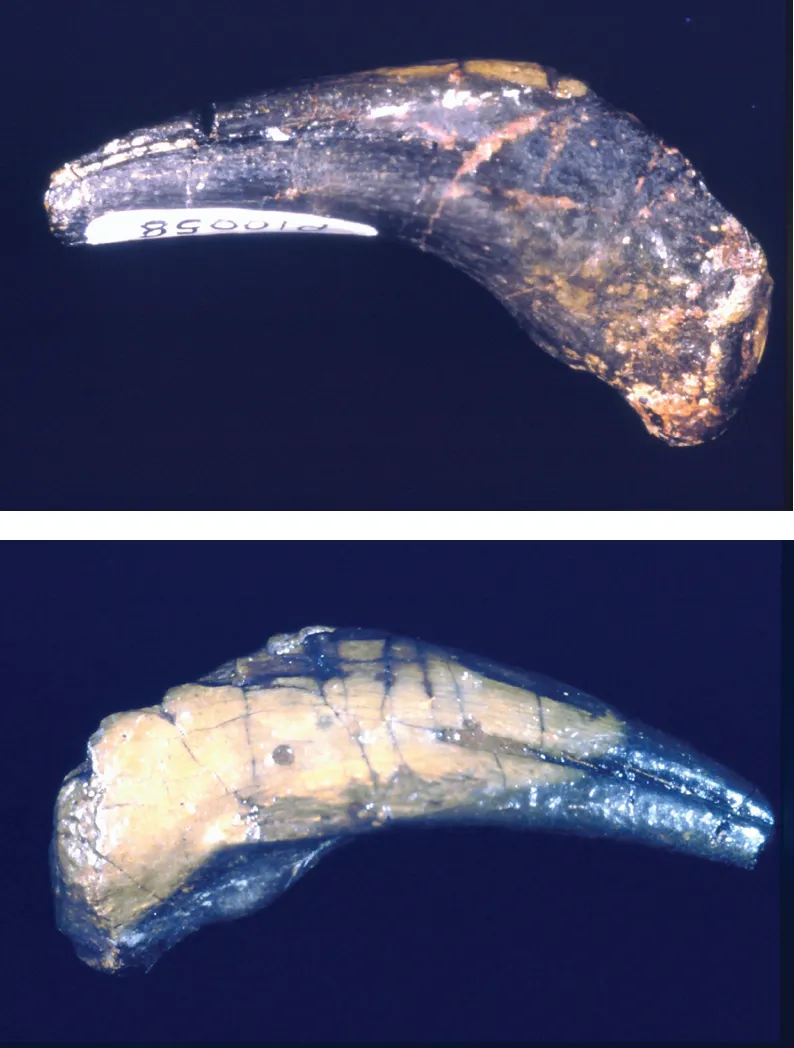

William Hamilton Ferguson was a Mines Department of Victoria geologist, who was searching for coal along the south coast of Victoria near the town of Inverloch in 1903. He possessed an uncanny knack for finding fossils where others could not. This is exactly what he did on that coast at a place immediately west of a prominent rock stack called Eagles Nest on May 7, 1903. There, he discovered and collected an isolated toe bone of a carnivorous dinosaur, the first dinosaur bone found in Australia to be described in a scientific paper. From the same site, he found a lungfish tooth. The locality of both specimens was meticulously marked on his exquisite geological map of the area.

1.2. The toe bone of the carnivorous dinosaur foun...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword by Frank C. Whitmore Jr.

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Dinosaur Cove

- 2. The Crossing of the Rubicon

- 3. Back to Dinosaur Cove

- 4. Interlude

- 5. Underground at Dinosaur Cove

- 6. New Explorations

- 7. Restoring the Life of the Past

- 8. The First Last Excavation of Dinosaur Cove

- 9. Other Eggs, Other Baskets

- 10. An Unexpected Surprise

- 11. Getting Through the Winter

- 12. Multiple Working Hypotheses

- 13. Showing Off the Polar Dinosaurs from Australia: Exhibitions and Popular Outreach

- 14. The Other Hemisphere

- 15. Where Are We Now and Where Are We Going?

- 16. Afterthoughts

- Index