![]()

1 Tourism Routes and their Identity

This first chapter introduces the fundamental nature of tourism routes.

1.1. The Taking and Following of Routes and Trails. A route is an itinerary that is known and determined. It can be planned and followed. It generally has a practical purpose, to guide people to a destination; but a route has other values.

1.2. Tourism on the Move. Routes are about travel and movement. They are ways of describing and defining the movement of travellers, for the convenience of the traveller and the benefit of local stakeholders.

1.3. Routes and Trails Providing Structure. Routes are ways of structuring tourism, of bringing together sites and tourism assets under a single brand and presenting them as a single experience.

1.4. Routes, Trails and Adventure. Routes enable connections between travellers and host communities, the environment and with themselves.

1.5. Routes and Identity. In all cases, routes have an identity and personality, more or less powerful, just as tourism destinations do.

1.1 The Taking and Following of Routes and Trails

This chapter asks some basic questions and starts with a first principle: that a route is a means of getting to a defined destination.

‘Route’ is a highly generic term. The ‘route to work’ may represent a walk to the end of the road we live on, followed by a bus ride along streets travelled every day. At the other end of the spectrum, in earlier centuries, the great explorers and traders of China and Europe opened up sea routes from one continent to another. What do these two examples have in common?

Routes are ‘discovered’ and trails are ‘followed’. It is as if they existed before there was anyone to travel them. The Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama ‘discovered’ the route to the Indies via the Cape of Good Hope. It implies that the journey is not some random wandering, but something that has been determined. A route is ‘looked up’ or ‘checked out’ on a map or on the Internet. A trail is ‘mapped’ or ‘planned’.

In many cases, routes and trails are attributed a value. Once, travellers might have wished to see holy sites along the way, or great cities, or markets where they could trade. In modern times, we might take the ‘scenic route’ or plot a route that allows us to stop off and see tourism sites, to eat in good restaurants, to visit friends. Our motivations, priorities and interests therefore accord some routes and trails greater value than others.

If we take as an example the route from Paris to The Hague, this same route is travelled by:

• People on business, motivated by work with the priority to get from A to B as quickly as possible.

• Families motivated to visit friends with the priority to break up the journey with functional stops.

• Leisure travellers motivated to drive between two cities with the priority to spend time in places of interest along the way.

The three journeys of this example provide different levels of route use and personal reward.

That there is a value in the journey itself isn’t a new idea. The Canterbury Tales by William Chaucer, written in Middle English in the 14th century, tells the story of a group of pilgrims riding from London to Canterbury, entertaining each other with stories as they rode. More than six centuries later, it will strike a chord with anyone who has taken a holiday with friends, or who has struck up friendships while on a cruise or tour.1

1.2 Tourism on the Move

Despite occasional inconvenience and discomfort, travelling is largely seen as a positive experience. We complain about crowded airports, delayed trains and cramped seats on planes, but – with the exception of jaded business travellers – leisure travel remains a pleasure and an adventure, even a relaxation. It may be a distant memory of a time when journeys were made to find better pastures or more plentiful game. Or it may simply be that a journey represents a break from routine or from a sedentary, urban lifestyle.

This book is about tourism on the move; the ‘places’ are steps or stages along the way. A route may have a final destination, but not always.

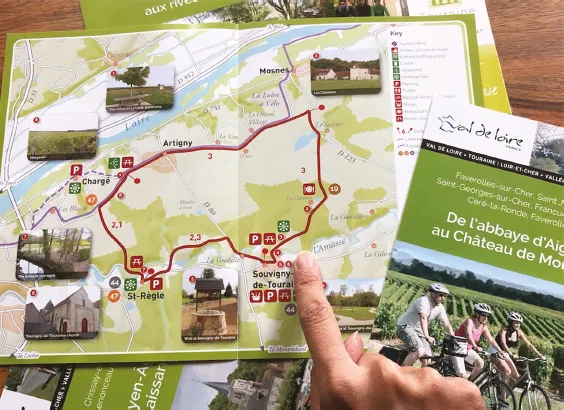

Fig. 1.1. The unity and identity of the Loire Valley is strengthened by its cycling routes and networks. Image: David Ward-Perkins.

Put simply, a tourism route is a way of structuring a journey, so that it is enjoyable for the traveller. An example is the Loire Valley (France), where the many tourism assets – including towns, castles, gardens – are typically presented and sold as routes or itineraries, to be travelled by car, by bicycle, by boat or on foot.

If presented any other way, tourists could be overwhelmed by the mass of information and choices.

1.3 Routes and Trails Providing Structure

A route can therefore be seen as a way of linking multiple sites in a structured and understandable way. It enables attractions and destinations to raise their profile, and to gain the attention of the market as part of a bigger entity in the fragmented and ultra-competitive tourism industry.

A good example is the Burgenstraße or German Castle Route. To quote a Route review by Tripsavvy:2 ‘If you want to see as many castles as possible in the least amount of time in Germany, take a ride on the Castle Road, one of Germany’s Best Scenic Drives. This themed route is lined with 70 castles and palaces, enough to make you feel like a King (or Queen)’.

Many tourists may indeed have limited time, and they will find the ability to visit numerous destinations along a single itinerary attractive. With good scheduling and a little advance planning, they can also take part in activities, events and festivals in towns along the way.

This ‘efficiency of experience’ can be seen as one of the primary purposes of a tourism route.

On the supply side, this has numerous implications:

• A need for excellent communication between the sites and attractions along the route, for example by developing a common calendar of events.

• Quality of information. The consumer needs to be able to access reliable and updated information, as much as possible from a single source.

• Providing information about access, transport and accommodation.

Such coordination becomes easier if the information is packaged under a single brand, like a named Route or Trail.

Multiple destinations mean multiple accommodations, transfers, tickets and so on, increasing the complexity and risk that something might go wrong. The richer the information, the more attractive it becomes when obtained through a single, branded source. It can be seen as a form of ‘clustering’, over an extended geographical area.

A strongly branded route will also be able to support the work of tour operators and other private enterprises. Working with accommodation providers and local guides, the modern tour operator can use the infrastructure to provide attractive, flexible packages. A tourism route therefore serves the interests of the whole tourist industry chain.

The example of the Burgenstraße is an excellent illustration of these principles.

1.4 Routes, Trails and Adventure

Travelling a route creates a connection between the traveller and the host communities encountered; with nature and wildlife and, most meaningfully, with themselves.

In the modern era of travel since the 1950s, a growing population of travellers has been motivated by these same desires: for a fresh experience, an expanded worldview, learning, challenge, meaningful connection, and often with an overall intention of some sort of personal transformation. To achieve their goals, they embark on independent or commercially supported ‘adventure travel’.

The Burgenstraße or German Castle Route

Starting in Mannheim and ending in Prague, the Burgenstraße is over 1,200 km (745 miles) long and links with over 70 castles and palaces. Crossing Germany from west to east through some of the country’s most famous heritage towns, the drive usually takes three or four days, although travellers may take much longer.

How the route developed

Launched in March 1954, the route was conceived as an initiative of the town of Heilbronn in partnership with the municipalities of Mannheim, Heidelberg, Rothenberg ob der Tauber, Ansbach and Nuremberg.

Early success was due in part to the creation of a public bus line called the ‘Burgenstraße’ that roughly followed the same itinerary. This name and this route became well known throughout Germany, as well as in neighbouring countries. Over time, other sites and towns entered the network. Following the fall of the Iron Curtain and the opening of the eastern border in 1989, the route was extended as far as Prague in 1994. Today the German Castle Route includes around 40 different towns and municipalities and promotes six different self-drive or guided itineraries.

Qualifying criteria to be part of the network include that the town must have a fortress, a castle, a palace, a monastery or an historic old town. Members are expected to maintain close and cooperative relations with each other, and with institutional and commercial partners including state-owned palaces and gardens and Premium Partner Hotels. Their goal is to provide the widest possible range of services and experiences to travellers on the route. The Burgenstraße is funded largely through its membership and through agreements with its partners.

Fig. 1.2. View from the Burgenstraße, a historic German driving route. Image: Electricmango/Dreamstime.com

Consumer marketing

The German Castle Route’s website, www.burgenstrasse.de, is the traveller’s main point of contact, offering route maps for inspiration, and suggestions to guide the selection and choice of different association partner restaurants and hotels.

Six different suggested itineraries involve a selection of destinations, where subpages give further detail about its characteristics, attractions and services. It acts as a portal directing consumers to the websites of accommodation providers and restaurants, venues with special events and their programmes.

The route is promoted with broad appeal for different types of tourists such as caravanners, cyclists and families travelling with children. This enables the website to provide focused guidance and suggestions targeting these specific audiences.

The business model

Perhaps mindful of the EU Package Travel Directive requirements, the association does not provide a direct booking service for the different attracti...