- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

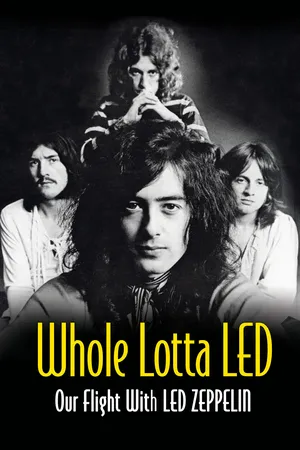

Whole Lotta Led: Our Flight With Led Zeppelin

About this book

In September 1968, four English lads gathered together for the first time in a small, stuffy London rehearsal room in a basement filled with wall-to-wall amplifiers. It was their first big tryout as musicians, and each of them was nervous. Would they come together as a band? Or would they crash and burn, becoming nothing but a rock footnote? Then the room exploded, with wailing chords, howling vocals, and a locked-tight rhythm section—a sonic assault of heretofore unknown power. Here for the first time was Led Zeppelin: the screaming rock guitar of Jimmy Page, the scorching blues vocals of Robert Plant, the driving jazz bass of John Paul Jones, and the power drumming of John Bonham. The session was amazing, electrifying, and stunning. The Zepp had arrived. There was no turning back. And rock entertainment would never be the same again.

Told by the band, the musicians, the groupies, and the fans themselves, this chronicle of one of rock's greatest and most innovative bands comes alive with the hiss of turntables, the sweat of the crowd at the Fillmore East, the hustle and bustle of backstage life, and the electricity of small clubs where rock history was about to be made. It's a story about a band's influence on two impressionable guys, and the countless others who came to get the Led out and stayed to become part of rock 'n' roll legend.

With exclusive and rare photos

Told by the band, the musicians, the groupies, and the fans themselves, this chronicle of one of rock's greatest and most innovative bands comes alive with the hiss of turntables, the sweat of the crowd at the Fillmore East, the hustle and bustle of backstage life, and the electricity of small clubs where rock history was about to be made. It's a story about a band's influence on two impressionable guys, and the countless others who came to get the Led out and stayed to become part of rock 'n' roll legend.

With exclusive and rare photos

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Whole Lotta Led: Our Flight With Led Zeppelin by Ralph Hulett,Jerry Prochnicky in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

“Shapes of Things”

Before there was Led Zeppelin, there were the Yardbirds. They ushered in the dawning of the heavy metal movement, of psychedelic music, of pushing back the boundaries of rock to someplace new. If there was just one word to describe the Yardbirds, it would be experimental. As suggested by the futuristic sound of their hit single “Shapes of Things,” this band pointed where rock music was headed. That direction was for the guitar to be the dominant instrument. In their five short years together, the Yardbirds became the training ground for three guitar legends to be: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Jimmy Page. There is also no other band that played such a pivotal role in the creation of Led Zeppelin.

Growing up with most 1960s bands meant that you followed the course of the artists’ singles and saved $3 to buy the next long-playing record. Yardbirds fans were different, especially on the West Coast where the band had a cult following. We often talked about how this band’s music sounded uniquely electric, nearly out of this world, and like no other British invasion group out there. We put Yardbirds concert posters and fliers from local music stores on our walls and religiously hunted down the latest releases and played them to our select friends. And some of us got really lucky and got to see the group live. But what made this band so different? They had no large mainstream following, like the Beatles or the Rolling Stones. The attraction of the Yardbirds was largely due to the free-form playing, with an emphasis on an unbridled, raw, and intense volume.

Because of the largely innovative nature of their material, they were ahead of their time, so they were unable to muster enough commercial appeal to regularly place themselves in the top 40 set. And underground FM rock radio hadn’t come into play yet. Plus, to their great misfortune the Yardbirds suffered from internal problems that perhaps kept the band from ever reaching its true potential. But there were still many exciting moments on their records, and at its height the music produced was on the cutting edge.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, while the Beatles were listening to Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, and Little Richard, the Yardbirds were searching record stores for rare sides by exotic names such as Howlin’ Wolf, Elmore James, Muddy Waters, and Sonny Boy Williamson. Formed in 1963, the Yardbirds (beat slang for a railroad hobo) consisted of Keith Relf, vocals and harmonica; Chris Dreja, rhythm guitar; Paul Samwell-Smith, bass; Jim McCarty, drums; and Eric “Slowhand” Clapton, lead guitar. Clapton’s ironic nickname was derived from the furious, speedy blues licks that he churned out onstage.

Looking for an opportunity to play their brand of music and to make beer money, in 1963 they auditioned and were hired at the famous Crawdaddy Club in Richmond, following the Rolling Stones’ residency there. Even though the Yardbirds had rhythm and blues roots like the Stones, they also slowly built their own style. This was prominently displayed on their stunning debut LP Five Live Yardbirds, which was recorded in 1964. It was also the first imported Yardbirds album that I laid eyes on.

I discovered it in a small record store in Laguna Beach, California, where my family had a small summer vacation home. This store was located downtown on the ocean side, where a variety of head shops were springing up, imitating San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury District. I walked along the Coast Highway to Cleo Street, where a two-story Victorian-style house had been converted into a vintage clothing store called Visions. I continued about three blocks north and stopped at a little shop at 533 Coast Highway that caught my eye. On the glass window were these red and orange letters that emanated out from a small pyramid-type design. In a psychedelic explosion of color and wild shape were the words Sound Spectrum.

Intrigued, I peered through the window. Nobody was inside. There were sawhorses with planks thrown across them, some paint buckets, and drop clothes. But there was something else, too: a plywood display wall with some imported records on it. I looked closer, pushing my head up against the window like any curious sixteen-year-old kid would do. My eyes scanned the display. They stopped at one in particular that had a huddled group of longhaired guys in a strange setting. The glare on the glass made it hard to see, so I shaded my eyes. Keith Relf and company stared back at me, looking like they were in jail behind an old, rusty, barred gate. Behind the group rose a high, imposing fortress-type wall. Below them was the name Five Live Yardbirds. I was spellbound. This was the debut Yardbirds album that I’d heard about from my friends, but I’d never seen it. Now it was staring me in the face! This little record shop would soon move half a mile south next to the Pottery Shack, but it has survived the passing years by always offering a little something or other you can’t find anywhere else.

The Beatles and Rolling Stones were gigantically popular in America by the mid-1960s with their Chuck Berry–and Buddy Holly–inspired form of rock and roll. By comparison, the Yardbirds played supercharged blues. Once I bought the Five Live Yardbirds album, a musical world entirely different from the Beatles and Rolling Stones was opened up. I always thought blues had to be played slowly, but I soon heard differently. All the songs seethed with fast-paced, rhythmic energy—they pulsated and flowed along in an array of blues-soaked intensity.

There was the frantically paced “Too Much Monkey Business,” where Clapton lived up to his nickname—notes flew out with lightning speed. Then there was “Smokestack Lightning” with its incredible interplay between Clapton’s guitar and Relf’s harmonica. Relf could blow a mean harp. The flow of the music rose to climaxes during “Respectable,” as well as the rollicking “Here ’Tis.” These both had a buildup of primitive rhythm and vocal interchanges that created images of natives in Africa, chanting and pounding their drums by jungle torchlight. The mixture of rock and blues was like nothing I’d ever heard; it was highly infectious and unbelievably exciting. There was a definite underground feel to this music. This constant improvisational rhythm that went back and forth like either gentle, rippling tides or violently crashing ocean waves came to be called the “rave up.”

This music was an early form of rock jamming, building more and more on the music’s inner rhythms than on a basic melody. The results were dynamic, with “Too Much Monkey Business” and “Smokestack Lightning” taking on long instrumental stretches. The harmonica and guitar moved together in geometric precision, sometimes wildly slicing the original song into segments that lasted as long as thirty minutes. For the most part, attention would be focused on the lead guitar. The first “Clapton Is God” graffiti appeared on buildings and walls all over London during his Yardbirds days.

As a lead player, Clapton would sound restrained in places and snake in notes during verses. But when a break came, all the power was forcefully unleashed. The Marquee Club audience whooped and shouted. But teenage girls didn’t scream wildly, tear their dresses, and throw panties and bras at the band, like they did at Rolling Stones shows. What shocking, crazy, and wild behavior! No, the Yardbirds’ audience was much more controlled. It was a strange irony: the music sounded chaotic, yet it didn’t create such wildness from the listeners. This could be because there was a basic blues framework that everything worked around, with the stabilizing force of Samwell-Smith’s bass, the chain-gang strumming of Dreja’s rhythm guitar, and McCarty’s precise yet unrestrained drums. Above it all soared Clapton’s leads, played with lighting-fast speed at times or stretched out slowly note by note. His blues playing style of bending notes and playing the guitar with an emotional feel was unheard of.

The live album was successful, but the group also wanted to break into the hit singles market and go national. Their two releases in June and October were failures, so the Yardbirds began to think seriously of changing directions. Change directions they did on their next single, “For Your Love,” which went straight to the top of the singles chart in 1965. The group hit pay dirt with a harpsichord and bongos sound. The harpsichord opening sounded so gothic coming out of AM radio. This was too much for Clapton, who considered himself a strict blues guitarist. He regarded “For Your Love” as a commercial betrayal of the band’s commitment to the blues. Disgusted, he packed his bags and joined John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers.

The Yardbirds had been wanting to replace Clapton with the session ace Jimmy Page. He was getting well known as a guitarist, having served an apprenticeship with anything the music business could throw at him. He had been anything but a late starter. At a young age, Page was seduced by the rock and roll of the 1950s. He was an only child and a loner who taught himself to play the guitar by practicing six to eight hours a day. The guitar was his salvation and sanctuary. In 1958, when Page was just fourteen, he had appeared on the BBC’s All Your Own program with his skiffle group, a British form that combined blues, folk, and country. Then in late 1960 Neil Christian saw Page playing in an amateur band. “He’d been in them about a year,” Christian remembered. “They started doing this Jerry Lee Lewis number and it was damn good. I knew the boy had something.... Jimmy lived and died by the guitar. Every time you went to see him he had a guitar around his neck.” Later, he did a stint with the newly formed Neil Christian and the Crusaders. The material they did was covers of Gene Vincent, Johnny Burnette, and Chuck Berry. Page now started to develop his own style and other guitarists came to watch him.

Despite the reputation he began to earn in the Crusaders, it came with a price. The band lived out of a van, at cafés, and at girlfriends’ homes. Sick with glandular fever, Page left the Crusaders in 1962 and decided to enroll in art school. He pursued painting and drawing, and became hugely influenced by the flamboyant and eccentric Spanish artist Salvador Dali. This painter created some of the most indelible visual images of the twentieth century that hold up in today’s surreal world. Excited about art, Page considered painting as a possible vocation. But he found that the guitar was still his first love, so his painting ambitions were put on hold.

He still kept in touch with the music scene by jamming at the Marquee Club. It was here that Page’s playing was noticed by the music arranger Mike Leander, who hired him as a session man. Page was now inducted into pop’s most subterranean universe, where the talents of unknown session players were almost as important as those of the artists whose names were on the records. The work was seven days a week, with three sessions lasting three hours each on a typical day. Page learned from producers and engineers how recording equipment worked, how arrangers made songs into records, and the way musicians interacted. In short, he got valuable studio experience for his later years with Led Zeppelin. The session singer and recording artist John Carter worked with Page during this time and praised Page’s ability. He noted, “Jimmy Page was a guy you could get a good performance from without trying. He was a very fast player, he knew his rock and roll and added to that. He would always get a good sound in the studio. He was very quiet and a bit of an intellectual (and interested in) all sorts of odd cult things.”

By 1965, session work had been incredibly productive and profitable for Page. He had worked with the Kinks and the Who, released a solo single, and became house producer at Immediate Records. He’d even produced some blues recordings with Clapton for Immediate and later recorded more blues jams at his Epsom home. Did Page want to turn his back on all this? Not yet; session work was going so well that Page turned down the offer to join the Yardbirds. But there was also another reason Page didn’t accept the position: Page and Clapton had become good friends. The two were going to dinner and sharing ideas about mutual subjects, such as art school, films, books, and music. To Page the offer may have looked too much like a cloak-and-dagger scenario. The Yardbirds’ manager came up to Page and offered him the guitarist spot in the band. Page considered this offer as being made behind Clapton’s back and so he turned it down.

Page recommended that Jeff Beck be offered the open position for the Yardbirds. This was no mere coincidence, because both musicians went back a long way. Both had been raised in Surrey, located just thirty miles south of London. They were the freaks—the 1 in 400 kids at school who played electric guitar. But their musical kinship brought them close together. As teenagers, they listened to and studied hard-to-get early American rock and blues albums that British teens treasured. Then they jammed and traded licks, inspiring and competing with each other.

Little did Page know that there were also three other teenage music freaks in England by the names of John Paul Jones, Robert Plant, and John Bonham. Jones first played church organ as well as piano. He wanted to be a bass player, although his dad insisted that he take up saxophone instead. But Jones had his mind made up, and the bass won over. He even had bass guitars drawn all over his schoolbooks and started playing bass at fourteen. Also, his dad’s shortwave radio picked up all sorts of radio stations. Jones was often glued to it, getting an earful of music education, and learned to play bass by playing along with whatever came on the air.

Robert Plant got his schooling from clubs instead of the classroom. He watched country, blues, and jazz performers and sat in the back, where he wouldn’t get noticed and thrown out for being underage. When he was fifteen, he decided to become a blues singer and learned to play harmonica. His influences ranged from Elvis Presley and Ray Charles to Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and especially Robert Johnson. For Plant, Johnson was a seductive music force whose playing weaved through both pain and anticipated pleasure. Plant started to concentrate on women and music instead of school subjects and let his hair grow long. Meanwhile, his parents wanted him to become an accountant or to go into some other profession. Their ambitions for him created too many conflicts. By the time he was sixteen, he had moved out to pursue music full time. He even went a step further and was living with his Calcutta-born girlfriend and future wife, Maureen, who he married when he was seventeen and had a baby girl, Carmen.

John Bonham always wanted to be a drummer, beating on his mom’s pots and pans. Even though he never had any drum lessons, one thing he never lacked was enthusiasm. He got his first snare drum at age ten and his first full drum kit by the time he was fifteen. Influenced by early soul records, he joined his first group. As a teenager, Bonham put in stints with various bands until he eventually met up with Plant, where he played blues in the Crawlin’ King Snakes. Their real schooling together, though, came with the next group, the Band of Joy. Like Plant, Bonham had married at seventeen. When Bonham wasn’t pounding the drums at night, he pounded a hammer by day at construction sites.

Unlike Page, Beck didn’t have any reservations about taking Clapton’s place in the Yardbirds. Beck recalled, “I was playing in a very good band called the Tridents, and they were always raving about the Yardbirds. I had never really heard them, but they were always talking about Eric Clapton this, and Eric Clapton that. I can tell you, I was getting pretty tired of that adulation for someone else. I was like, ‘Fuck Eric Clapton,’ you know, I’m your guitarist.”

In reality, Beck wasn’t making much money from the Tridents; there were times that he could hardly afford guitar strings. By March 1965 and for the next twenty months, Beck was in the lead guitarist’s chair for the Yardbirds. But whereas Clapton had kept the band firmly grounded in the blues, Beck’s impact on the Yardbirds was to push the band in a much more avant-garde direction. The power of his Fender Esquire electric guitar was unleashed via unearthly sounds filled with distortion, feedback, echo, and fuzz tone pumped hard through his twin Vox AC30s.

The first American Yardbirds album, For Your Love, was released the summer of 1965. Some singles cut with Clapton such as “I Ain’t Got You” were included, as was a Freddy King–style instrumental entitled “Got To Hurry,” which showed Clapton’s clear, precise, blues breaks. Beck emulated Clapton’s style with the licks on “I Ain’t Done Wrong,” but he added some new touches here and there as well, such as the use of fuzz tone. Page had used it on various sessions like on his work with the Who. Beck employed it on “I’m Not Talking,” the buzzing lead sounded like an angry wasp zooming about madly in a box, trying to escape. Beck’s creative playing was now a part of the Yardbirds’ sound. He would become a guitar hero, partly from his guitar work and partly from the image that he presented. The manager Giorgio Gomelsky had gotten Beck a pudding-basin haircut and flashy Carnaby Street clothes. Beck was being noticed more and more for his guitar workouts in London gigs. With his eyes closed, he used volume and striking his strings in ways that forced distortion from the amps. He’d lean his guitar against the amplifiers and get the tone droning, then wrench screams of feedback that virtually leaped out at the audience. He made playing feedback look easy. But Beck said about this gimmick that “your immediate reaction is to go over and turn it off. You think it’ll hurt the instrument, but after a while you find that it can contribute something. I like using many different effects and noises. It’s something very hard to control and it’s hard to do in tune.”

The Yardbirds left their British turf for the United States in the summer of 1965. “Heart Full of Soul” was a single then, and the group needed to generate support for it. Beck had only joined the group three months prior, and he was already leaving on his first tour. Before he left, he stopped by Page’s house. He handed Page a collector’s item in guitar circles: a 1958 Fender Telecaster. There had developed a musical kinship between the two that nearly surpassed friendship. As far as gifts went, Beck sure knew how to pick something for Page. This was the least he could do—after all, Page had placed Beck smack into stardom.

For a first tour, everything seemed to go well. According to Gomelsky, America was a whole new world and the group was enthusiastically received at shows. “I think people who saw those gigs will always remember them: the Yardies were possibly the most advanced group that was around then. The impact was made in those live performances. But the pressures of success can exhaust young and inexperienced people, which they all were. But no one had any experience of touring America: it was a completely new trip.”

Before 1965 ended, Bo Diddley’s “I’m a Man” and “Shapes of Things” both turned out to be huge hit singles in America. With Beck’s and Relf’s classic call-and-response between harmonica and guitar on “I’m a Man,” the Yardbirds’ wild rave-up rhythms pulsated for the first time ever on Top 40 radio. Beck held all six strings down on his guitar neck and stuck them at the same time, which made the sound of a chicken running madly across the road. Along with this was the pounding rhythm of Samwell-Smith’s bass and McCarty’s smashing drums The results were devastating: carved from the 1960s pop music was a new niche by the Yardbirds’ frantic, hardhitting music. As far as “Shapes of Things” went, it was aptly named, for this song took the Yardbirds into a new musical dimension. It stood out for Beck’s sonically charged guitar parts and the unique ending, where his Telecaster sounded like Ravi Shankar’s sitar as it faded out. Also, the lyrics made it an ahead-of-its-time antiwar song. The lyrics asked, “Shapes of things before my eyes, just teach me to despise, will time make man more wise?” Vietnam had some American advisors, but President Lyndon B. Johnson hadn’t escalated the war to the seething controversy that it would later become.

I asked my mother about Vietnam around 1966. Was it going to get worse? Would I have to go there when I was out of high school? She answered, “Don’t worry, you won’t be out of school for three more years. By then the whole thing will be over. The president will fix it. I wouldn’t worry about it at all, Ralph.” At the time, those words were pretty comforting to me, and I went back to pursuing the things that teenagers enjoy: hanging out with friends, listening to music, and playing sports like baseball and basketball. I started changing when I adopted the surfing lifestyle. There were great breaks in Laguna, like Brooks Street, which on a large swell boasted powerful waves, and also Thalia, a reef break a few blocks north that often had hollow, smaller waves. Communing with nature by riding wave...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- FOREWORD

- CHAPTER 1 - “Shapes of Things”

- CHAPTER 2 - “You Shook Me”

- CHAPTER 3 - “Over the Hills and Far Away”

- CHAPTER 4 - The Four Symbols

- CHAPTER 5 - Houses of the Holy

- CHAPTER 6 - Physical Graffiti

- CHAPTER 7 - Presence

- CHAPTER 8 - “Achilles Last Stand”

- CHAPTER 9 - “In My Time of Dying”

- EPILOGUE

- LED ZEPPELIN DISCOGRAPHY

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- ABOUT THE AUTHORS

- Copyright Page