eBook - ePub

What Really Sank the Titanic:

New Forensic Discoveries

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Was the ship doomed by a faulty design?

Was the hull's steel too brittle?

Was the captain negligent in the face of repeated warnings?

On the night of April 14, 1912, the "unsinkable" RMS Titanic, with over 2,200 passengers onboard, struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic and plunged to a watery grave. For nearly a century, the shocking loss has haunted the world. Now the same CSI techniques that are used to solve modern murder cases have been applied to the sinking of history's most famous ship. Researchers Jennifer Hooper McCarty and Tim Foecke draw on their participation in expeditions to the ship's wreckage and experiments on recovered Titanic materials to build a compelling new scenario. The answers will astound you.. . .

Grippingly written, What Really Sank the Titanic is illustrated with fascinating period photographs and modern scientific evidence reflecting the authors' intensive study of Titanic artifacts for more than ten years. In an age when forensics can catch killers, this book does what no other book has before: fingers the culprit in one of the greatest tragedies ever.

"A fascinating trail of historical forensics."

--James R. Chiles, author of Inviting Disaster>/I>

"An essential facet of Titanic history. Five stars!"

--Charles Pellegrino, author of Her Name Titanic

With 16 pages of photos

Was the hull's steel too brittle?

Was the captain negligent in the face of repeated warnings?

On the night of April 14, 1912, the "unsinkable" RMS Titanic, with over 2,200 passengers onboard, struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic and plunged to a watery grave. For nearly a century, the shocking loss has haunted the world. Now the same CSI techniques that are used to solve modern murder cases have been applied to the sinking of history's most famous ship. Researchers Jennifer Hooper McCarty and Tim Foecke draw on their participation in expeditions to the ship's wreckage and experiments on recovered Titanic materials to build a compelling new scenario. The answers will astound you.. . .

Grippingly written, What Really Sank the Titanic is illustrated with fascinating period photographs and modern scientific evidence reflecting the authors' intensive study of Titanic artifacts for more than ten years. In an age when forensics can catch killers, this book does what no other book has before: fingers the culprit in one of the greatest tragedies ever.

"A fascinating trail of historical forensics."

--James R. Chiles, author of Inviting Disaster>/I>

"An essential facet of Titanic history. Five stars!"

--Charles Pellegrino, author of Her Name Titanic

With 16 pages of photos

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access What Really Sank the Titanic: by Jennifer Hooper McCarty,Tim Foecke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THE BACKGROUND

CHAPTER 1

THE YARD

The morning sun rose up from behind the Queen’s Road tramcar as it clattered along the track, jostling the dark coats and caps clinging to every last joist on the way toward Queen’s Island. As it slowed on the approach toward The Yard, the passengers disembarked into a sea of black, the hustle and bustle of thousands of shipyard workers, undulating back and forth, as crowds merged and streams of men descended from other trams. Here the crowd swelled into a parade of marchers, then narrowed into a long black ribbon, scurrying along the edge of the tracks to beat the 8 a.m. horn.

From another direction, a more distinguished set of men trickled into the main offices, while preparations were underway for a meeting of the managing directors. The board had gone into crisis mode. Faced with the daunting construction of several large vessels at once, the loss of workers to other yards, and a dwindling sense of worker efficiency, Lord W. J. Pirrie, chairman of Harland & Wolff, and his associates were forced to consider a reorganization of laborers that would improve their situation.

The riveters’ work at the Yard had been tough during the last few months of 1911 and into the winter of 1912. According to shipbuilding records, the foreman, Mr. Kingan, had resorted to becoming unduly stern with the workers, formally complaining of their idling on the job. Harland & Wolff was one of the most powerful shipbuilders in the world, yet in the early spring of 1912, it certainly didn’t need to add laziness to its latest troubles. For the first and last time in history, the White Star sisters Titanic and Olympic found themselves quartered next to one another at the gantry in Belfast, Ireland, as seen in plate 1.1 On March 2, 1912, the older sister, Olympic (on the left), was dry-docked after a collision stripped her of a propeller blade, and the Titanic, poised to break the record books, instead wallowed months behind schedule, now bereft of a propeller blade.

Each day the workers were forced to move faster, accelerating their speed, pounding away with the precision of a well-oiled machine. Harland & Wolff’s board members took to panicking over lost days and diminishing materials, setting in motion a pandemonium of activity to finish the job at any cost, be it financial or human. According to Harland & Wolff’s records, before the Titanic even left the River Lagan, eight people had died on the job, and a list of those maimed or injured because of work-related accidents “read like a roster of the wounded after battle.” A total of 254 work-related accidents occurred during her construction. It’s hard to say which employees got the brunt of the criticism; however, it was the riveting squads who were deemed most crucial to the shipbuilder’s fame. The faster they worked, the earlier Titanic’s structure would take shape and the sooner Harland & Wolff could breathe a sigh of relief.

Even the less-experienced rivet boys, some as young as thirteen, knew that a ramp-up in production meant pressure on the lines. Every iron rivet had to be perfectly heated to just the right color of flaming cherry red. If too hot or too cold, they didn’t “rivet up” properly—the shipbuilder’s way of saying that the rivet was too loose to create that all-critical watertight seal between the plates.

It was the rivet counter’s job to oversee the whole process—a duty that became a source of real animosity among the riveting gangs. In between pointing out weaknesses and reprimanding the lollygaggers, the rivet counter inspected the completed rivets, or at least as many as he could conceivably check during a shift. This manual inspection was more than merely a daunting task—it became an impossibility on a ship built with over three million rivets.

On the production lines, the rivet boys pumped the stove bellows with their feet until they sweat, getting the coke stoked just right. Fresh in their teens, local boys were plucked for the job from around the Belfast countryside when Harland & Wolff was looking for workers to help on the new passenger steamers. The conditions were gruesome, standing for a nine-hour shift in the bitterly cold weather and unbearable noise. For many, even the hot stove and the steady pumping of their feet weren’t enough to warm them from the cold, wet Belfast winter. Despite the hardship, at least it provided the working class with some income.

The magic of the Edwardian Age was that it managed to prolong the Victorian belief in progress and the energy for invention, despite the rampant poverty that pervaded the working class. Belfast had become the industrial powerhouse of Ireland, wooing skilled workers from the surrounding areas to participate on the manufacturing lines. Yet, at the same time, a mass emigration from the surrounding counties supplied Harland & Wolff’s inexhaustible needs for unskilled labor. Belfast yards paid more than most to the skilled engineering workers, but only about half that much was offered to unskilled laborers and apprentices, a wage consistently lower than in most shipbuilding centers.

At the Yard, Monday morning was the busiest time, because the rivet gangs rushed to drive the first rivets of the workweek. As soon as the horn blew, heater boys clamped their rivets over the coals and watched them heat up until glowing red. The familiar smells of grease, rust, and hot metal wafted through the air, and the men bustled about the gantry, a steel goliath looming over them, while the heater boys picked up Titanic rivets in their tongs. The bright red slugs of metal warming their faces signaled a critical moment in the production lines. Once installed, the rivets were the glue that held the ship together, the watertight seals that ensured her flotation. In most cases, ships faced the typical stresses and strains caused by high winds or rough wave patterns at sea. The stakes rose dramatically when a ship’s structure was challenged to withstand an iceberg collision.

The evidence to interpret history’s most famous marine disaster begins at her beginning—at the shipyard in the hands of common people. Their focus on the job, the attention to detail, and the quality of the materials they used had a direct influence on the success of the ship’s maiden voyage, whether good or bad. In 1911, there were 1,728 unskilled workers at the Harland & Wolff shipyard, comprising between 17 percent and 23 percent of the workforce in any one month. They were overworked and under pressure. On October 16, 1911, Lord Pirrie decided against an incentive measure to increase wages for riveters who kept good time on the job. During the next six months, the board discussed idleness on the job, reorganization of the labor force, and sources for additional riveters at every single meeting. Between December 1909 and January 1912, at least four forges were utilized as suppliers of rivet material to make more than fifteen different types of rivets. Just as the great ship, No. 401 Titanic, sat poised for completion, a coal strike forced the Harland & Wolff board members to reevaluate the speed of their ships and the distances they could travel. Did any of these factors play a part in the sinking of the unsinkable ship Titanic? The human factor cannot be avoided in disaster analysis, and what we know about the lives of the builders of the Titanic may help in sifting through the facts.

The shipyard workers and the city of Belfast celebrated with admiration as the ship born from their sweat sprung from the Queen’s Island docks into the Belfast Lough on April 2, 1912. The feelings of ownership and the sense of worth that had emerged among a society torn apart by religious animosity and bigotry were overwhelming. The Titanic was on view for the entire world to see—a product of the hardworking Irish and a masterpiece formed by the united hands of a city plagued by political strife. The citizens were direct contributors and their men the creators, designers, and builders of the largest manmade moving object on Earth. Spectators crowded together to wave good-bye to the grand manifestation of their hopes and dreams, never suspecting that it would soon become the greatest source of loss and bewilderment that the country had ever experienced.

CHAPTER 2

BUILDING THE GREAT LEVIATHAN

A Guide to Titanic’s Details

Despite the workers’ plight of the early 1900s, the optimism of early-twentieth-century science and technology could not be squelched. Discoveries and inventions that claimed new feats of mastery over nature were becoming almost commonplace: the discovery of X-rays (1895), the invention of the Zeppelin airship (1897), the first powered flight by the Wright brothers (1903), Einstein’s Theory of Relativity (1905), the launching of the first Dreadnought (1906), and Rutherford’s model of the atom (1911). The steel industry, the design of huge machinery, and the invention of the internal combustion engine had changed passenger transport forever. The transatlantic Blue Riband race (the world’s most glamorous speed record for crossing the Atlantic) began in 1838 and instigated construction of the fastest steamships in the world. People were swept up in a bubble of confidence, marveling with pride at the technological miracles and new discoveries that had carried through the turn of the century. The New York Times brilliantly expressed the sentiments of the Golden Age on New Year’s Eve 1899, “We step upon the threshold of 1900, which leads to the new century, facing a still bright dawn of civilization.”

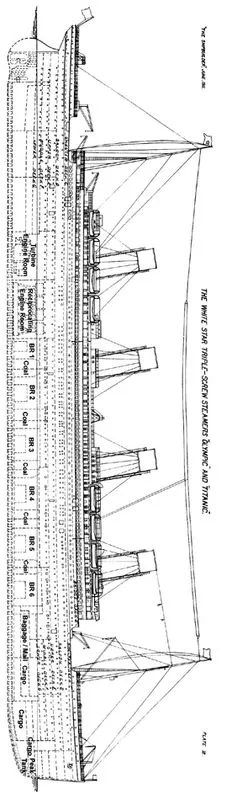

Figure 1

FLOATING PALACES

In the early 1900s, Britain dominated the shipbuilding industry in terms of output, but not without some serious rivalry. For centuries, enormous quantities of available coal and rapid advances in iron and steel production made her impervious to competition from the Germans or the Americans. But by the late 1800s, other players entered the ring. In 1897, British smugness was quickly broken by Germany’s offering to the transatlantic passenger trade because the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse won the coveted Blue Riband trophy. At 627 feet in length and 14,349 tons, this North German Lloyd creation was the first modern luxury liner and received a huge portion of transatlantic business. Soon after, the company followed with three similar ships, and the Hamburg-Amerika line chimed in with the four-funneled Deutschland. The Germans had seized the Blue Riband and, with it, Britain’s national prestige. The White Star Line had countered with the Oceanic in 1899, but this largest and most luxurious liner was not the fastest because her designers favored passenger comfort over speed. In 1902, the American business tycoon J. Pierpont Morgan bought out the White Star Line as part of his conglomerate, the International Mercantile Marine Company, and happily used his capital to extend the sumptuous style and lavish artistry of the company’s ships. Morgan deftly formed a partnership with North German Lloyd as well.

Meanwhile, the British government was horrified that the roost it had ruled for centuries was being simultaneously culled by the Germans and gobbled up by the Americans. British businessmen anxiously followed the dwindling passenger lists, sickened by the losses that competing foreign lines had scooped up. A member of the North East Coast Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders summed it up in a presentation to his colleagues: “There is ... the larger and more important national view which has to be borne in mind ... that by far the larger number of the passengers crossing the Atlantic are now carried by the German and the French lines, whilst only a comparatively small number are patronizing the English boats.”

The government was certainly not immune to this public embarrassment, and so in support of regaining the transatlantic speed record, it subsidized Cunard to build the world’s next great liners: Lusitania and Mauretania, both Blue Riband winners. Not only did Cunard succeed, the company managed to design the largest, fastest, most luxurious passenger ships to date, using the extravagance typical of English stately homes to create floating palaces. Cunard’s creations ushered in the transformation of twentieth-century liners from frugal seagoing transportation to regal accommodation, replete with plush bedrooms, glistening ballrooms, and the very latest in haute cuisine. Cunard’s feat won incredible support and popularity from the public and quickly stripped the White Star Line of any claims to fame. Under pressure from the success of Cunard’s masterpiece and speculation over the lucrative future of German ventures, Lord Pirrie, head of Harland & Wolff, and Bruce Ismay, managing director of the White Star Line, came to the table to devise a counterattack, whose sheer size and m...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- PART I - THE BACKGROUND

- PART II - THE FACTS

- PART III - THE ANALYSIS

- PART IV - THE REST OF THE STORY

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- GLOSSARY

- WHO’S WHO - in What Really Sank the Titanic

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Copyright Page

- Notes