The Student's Guide to Cognitive Neuroscience

- 526 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Student's Guide to Cognitive Neuroscience

About this book

Reflecting recent changes in the way cognition and the brain are studied, this thoroughly updated fourth edition of this bestselling textbook provides a comprehensive and student-friendly guide to cognitive neuroscience. Jamie Ward provides an easy-to-follow introduction to neural structure and function, as well as all the key methods and procedures of cognitive neuroscience, with a view to helping students understand how they can be used to shed light on the neural basis of cognition.

The book presents a comprehensive overview of the latest theories and findings in all the key topics in cognitive neuroscience, including vision, hearing, attention, memory, speech and language, numeracy, executive function, social and emotional behavior and developmental neuroscience. Throughout, case studies, newspaper reports, everyday examples and studentfriendly pedagogy are used to help students understand the more challenging ideas that underpin the subject.

New to this edition:

- Increased focus on the impact of genetics on cognition

- New coverage of the cutting-edge field of connectomics

- Coverage of the latest research tools including tES and fNIRS and new methodologies such as multi-voxel pattern analysis in fMRI research

- Additional content is also included on network versus modular approaches, brain mechanisms of hand-eye coordination, neurobiological models of speech perception and production and recent models of anterior cingulate function

Written in an engaging style by a leading researcher in the field and presented in full color including numerous illustrative materials, this book will be invaluable as a core text for undergraduate modules in cognitive neuroscience. It can also be used as a key text on courses in cognition, cognitive neuropsychology, biopsychology or brain and behavior. Those embarking on research will find it an invaluable starting point and reference.

This textbook is supported by an extensive companion website for students and instructors, including lectures by leading researchers, links to key studies and interviews, interactive multiple-choice questions and flashcards of key terms.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introducing cognitive neuroscience

Cognition

Cognitive neuroscience

Mind–body problem

Dualism

Dual-aspect theory

Reductionism

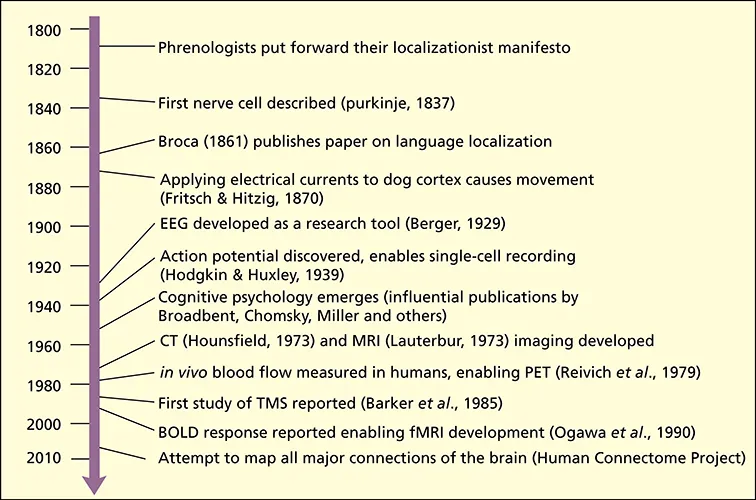

Cognitive Neuroscience in Historical Perspective

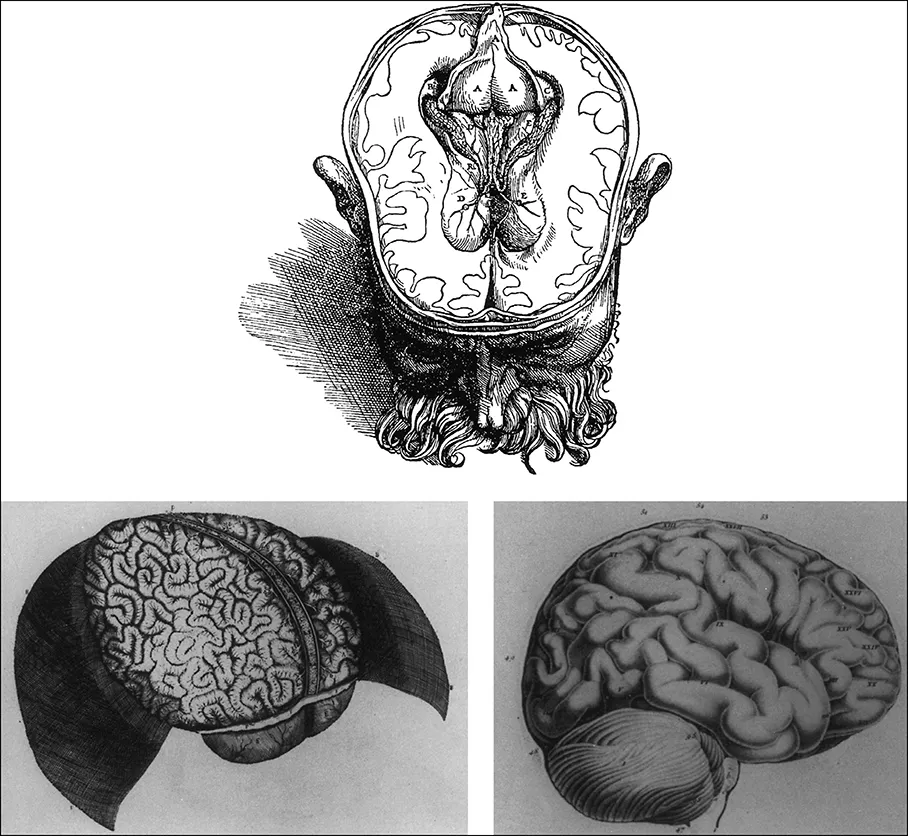

Philosophical approaches to mind and brain

Scientific approaches to mind and brain

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- The Student’s Guide to Cognitive Neuroscience

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- About the author

- Preface to the fourth edition

- 1 Introducing cognitive neuroscience

- 2 Introducing the brain

- 3 The electrophysiological brain

- 4 The imaged brain

- 5 The lesioned brain and stimulated brain

- 6 The developing brain

- 7 The seeing brain

- 8 The hearing brain

- 9 The attending brain

- 10 The acting brain

- 11 The remembering brain

- 12 The speaking brain

- 13 The literate brain

- 14 The numerate brain

- 15 The executive brain

- 16 The social and emotional brain

- References

- Author index

- Subject index