eBook - ePub

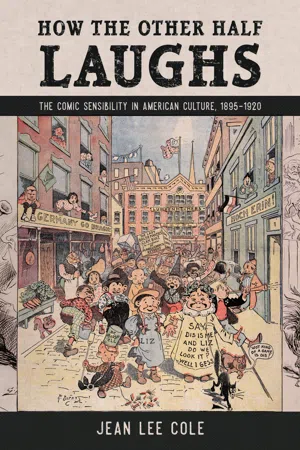

How the Other Half Laughs

The Comic Sensibility in American Culture, 1895-1920

- 214 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

2021 Honorable Mention Recipient of the Charles Hatfield Book Prize from the Comics Studies Society

Taking up the role of laughter in society, How the Other Half Laughs: The Comic Sensibility in American Culture, 1895–1920 examines an era in which the US population was becoming increasingly multiethnic and multiracial. Comic artists and writers, hoping to create works that would appeal to a diverse audience, had to formulate a method for making the "other half" laugh. In magazine fiction, vaudeville, and the comic strip, the oppressive conditions of the poor and the marginalized were portrayed unflinchingly, yet with a distinctly comic sensibility that grew out of caricature and ethnic humor.

Author Jean Lee Cole analyzes Progressive Era popular culture, providing a critical angle to approach visual and literary humor about ethnicity—how avenues of comedy serve as expressions of solidarity, commiseration, and empowerment. Cole's argument centers on the comic sensibility, which she defines as a performative act that fosters feelings of solidarity and community among the marginalized.

Cole stresses the connections between the worlds of art, journalism, and literature and the people who produced them—including George Herriman, R. F. Outcault, Rudolph Dirks, Jimmy Swinnerton, George Luks, and William Glackens—and traces the form's emergence in the pages of Joseph Pulitzer's New York World and William Randolph Hearst's Journal-American and how it influenced popular fiction, illustration, and art. How the Other Half Laughs restores the newspaper comic strip to its rightful place as a transformative element of American culture at the turn into the twentieth century.

Taking up the role of laughter in society, How the Other Half Laughs: The Comic Sensibility in American Culture, 1895–1920 examines an era in which the US population was becoming increasingly multiethnic and multiracial. Comic artists and writers, hoping to create works that would appeal to a diverse audience, had to formulate a method for making the "other half" laugh. In magazine fiction, vaudeville, and the comic strip, the oppressive conditions of the poor and the marginalized were portrayed unflinchingly, yet with a distinctly comic sensibility that grew out of caricature and ethnic humor.

Author Jean Lee Cole analyzes Progressive Era popular culture, providing a critical angle to approach visual and literary humor about ethnicity—how avenues of comedy serve as expressions of solidarity, commiseration, and empowerment. Cole's argument centers on the comic sensibility, which she defines as a performative act that fosters feelings of solidarity and community among the marginalized.

Cole stresses the connections between the worlds of art, journalism, and literature and the people who produced them—including George Herriman, R. F. Outcault, Rudolph Dirks, Jimmy Swinnerton, George Luks, and William Glackens—and traces the form's emergence in the pages of Joseph Pulitzer's New York World and William Randolph Hearst's Journal-American and how it influenced popular fiction, illustration, and art. How the Other Half Laughs restores the newspaper comic strip to its rightful place as a transformative element of American culture at the turn into the twentieth century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access How the Other Half Laughs by Jean Lee Cole in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Comics & Graphic Novels Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University Press of MississippiYear

2020Print ISBN

9781496826534, 9781496826527eBook ISBN

9781496826541CHAPTER ONE

The Comic Grotesque

Technique, did you say? … Guts! Guts! Life! Life! That’s my technique!

—George Luks1

—George Luks1

By the early 1890s, Mark Twain had been recognized for decades as the foremost of “American humorists.”2 Yet in his golden years, he seemed to have lost his way; he certainly wasn’t funny, at least to most people most of the time. Scholars have noted Twain’s “turn to darkness,” reflected in the increasing bitterness of his social commentary, veering toward invective, especially regarding the United States’ ventures in Hawaii, the Philippines, and Cuba. He seemed to have lost his footing in the American comic landscape as well. In “How to Tell a Story,” he lambasted the teller of what he described as the “comic story,” who tells his joke “with eager delight” and “is the first person to laugh when he gets through.” The punch line? “He shouts it at you—every time.” For Twain, the problem with the joke—a staple of the New Humor of the 1890s—was that it demanded no subtlety or nuance. No sleight of hand was needed to tell a joke; a “machine could tell” it. In short, he lamented, “It is a pathetic thing to see.”3 Daniel Wickberg writes that Twain’s objections to the joke reflected a shift in the perception of humor, a shift away from the personality or skill of the teller and onto the content of the joke itself. If the punch line could be shouted, delivered by a machine, it could be delivered by anyone.4 Indeed, during this time, jokes became a cultural commodity, produced by the hundreds—even thousands—by professional joke writers, whose products were sold to the popular humor weeklies such as Puck, Judge, and Life and printed and reprinted, without byline or attribution, in magazines and newspapers all over the country.5

If a joke could be told by anyone, even a machine, then had not humorists become reduced to machines themselves? Susan Gillman notes that Twain’s writing during this period revolved around questions of his identity as an author;6 in an environment where authors had become celebrities, “personalities,” paid by the word or by the inch for their poetry, stories, and novels, were authors autonomous creators of art? Or were they, like the professional joke-tellers, interchangeable and faceless producers of cultural matter, mere manufacturers of entertainment?7

At the same time that Twain felt himself erased as an author, he also found himself more and more alienated from his fellow citizens, people whom he felt distinctly unlike, yet was called upon to include in his vision of the American nation. Twain’s writings on Siamese twins, culminating in the twin narratives The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson and The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins (1894), explore the possibility of “a unitary, responsible self” in an American society that seemed increasingly chaotic or even anarchic in its makeup. On the one hand, individuals seemed nothing more than machines, identical and endlessly reproducible; on the other, the polyglot society of the late nineteenth-century United States seemed unmendably fractured. Gillman writes that in works like Pudd’nhead Wilson, Twain appealed to legal and scientific definitions of personhood in order to determine who was real and who was not, to determine “whether one can tell people apart, differentiate among them.” For, “without such differentiation, social order, predicated as it is on division—of class, race, gender—is threatened.”8

In both Pudd’nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins, Twain calls upon what Leonard Cassuto has termed the racial grotesque in his exploration of identity, classification, and differentiation. Tom Driscoll, born Valet de Chambre, believes he is white and unthinkingly assumes all of the privileges his presumed whiteness affords him; the real Tom Driscoll, switched for Valet de Chambre by his desperate mother, Roxy (who is only one-sixteenth black and could pass for white herself), believes he is “all black.” As a result, Chambers, as he is known, adopts the “manners of the slave”: he becomes subhuman, if not almost absent of human characteristics altogether. When their “real” identities are revealed, Tom and Chambers are unable to embody them. Of Chambers (the real Tom), Twain writes: “The poor fellow could not endure the terrors of the white man’s parlour, and felt at home and at peace nowhere but in the kitchen. The family pew was a misery to him, yet he could nevermore enter into the solacing refuge of the ‘nigger gallery’—that was closed to him for good and all.”9 Chambers becomes, in Cassuto’s words, “the anomalous embodiment of cultural anxiety,” the racial grotesque, which “is born of the violation of basic categories. It occurs when an image cannot be easily classified even on the most fundamental level: when it is both one thing and another, and thus neither one.”10 Those Extraordinary Twins, Twain’s supposedly comic story of the Siamese twins Luigi and Angelo Capello, also ends in a grotesque tableau, albeit one based on their identity as “freaks” (or as a single freak), rather than their racial difference. The twins are judged as separate individuals, one innocent, one guilty. However, when Luigi is hung for the crime he has committed, Angelo must die along with him; in the end, they comprise a single biological entity, a single body.

As his depiction of the Capello twins implies, Twain’s notion of the grotesque applies not just to race and ethnicity, but also to the essential composition of the human body. In Playing the Races, Henry Wonham performs an extended reading of Twain’s late work “Three Thousand Years Among the Microbes,” where Twain imagines a cholera microbe (oddly given two names, Bkshp and Huck) coursing through the body of a recent Hungarian immigrant named Blitzkowski. While Blitzkowski is easily identified as the quintessential, stereotypical Eastern European immigrant (“wonderfully ragged, incredibly dirty”), Bkshp/Huck discovers that Blitzkowski’s body “contains swarming nations of all the different kinds of germ-vermin that have been invented for the contentment of man.”11 Wonham writes of this anecdote that “the joke might be summarized as follows: what appears to be one turns out to be many”; what appears to be “a knowable, unitary type” is revealed to be “a complex of different entities and energies.”12 This is, of course, exactly how the author/humorist Twain wished to view himself, as a complex individual rather than a unitary “type.” At the same time, Blitzkowski is no different from anyone else: we are all simply collections of molecules, not to mention microbes. Yet certainly Bkshp/Huck—much less Twain—clearly is repulsed by him; he wishes to be differentiated from him.

The grotesque, as it emerges in Twain’s work, is a twin realization that things that appear to be different are actually equivalent, and also, that what appears to be a single entity is in fact full of difference. Hungarian immigrants and native-born Americans (not to mention blacks and whites and Siamese twins) have differentiating characteristics, yet they are all members of the same species, Homo sapiens, and also, ostensibly, the same nation, the United States. At the same time, no one, least of all Twain, could deny that the unum that comprised the American nation was also the pluribus, whether that plurality was made up of different ethnicities or simply human individuals. Cassuto writes that the racial grotesque reflects a “desire for order” but also is an acknowledgment of actual disorder; if the categories and classifications by which one builds societies are shown to be permeable and fluid, then society itself is shown to be nothing more than a willful act of the imagination.13

Regardless of whether difference is rooted in race, ethnicity, or biology, few thought any of it was funny. Twain himself seemed far more disturbed than amused by the grotesque form of American society at the end of the nineteenth century. In the “Final Remarks” he wrote at the conclusion of the combined edition of Pudd’nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins, Twain apologized for having subjected his readers to such “an extravagant sort of tale,” one that “had no purpose but to exhibit that monstrous ‘freak’ in all sorts of grotesque lights.”14 He explains that having begun the story of Tom, Roxy, and Chambers, it “began to take a tragic aspect,” while the characters comprising the “twin-monster,” the Capello twins, “were merely in the way.” Unlike Siamese twins, he decided, his stories had “no connection between them, no interdependence, no kinship.” And so he split the story into two, in what he described as a “literary caesarean operation.”15 Critics have found Pudd’nhead Wilson a puzzling if not wholly inferior work within Twain’s oeuvre, even while acknowledging the general unevenness of Twain’s work as a whole. Malcolm Bradbury, for one, succinctly described it as “a bad book with a good book inside it struggling to get out.”16 Bradbury yearns for the “good” Twain, the affable, genial, funny Twain, to “get out”—but all the “bad” societal stuff gets in the way.

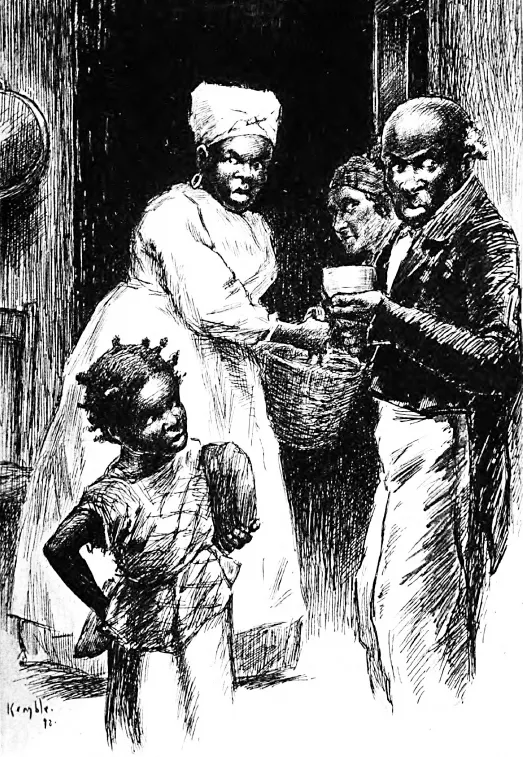

Gillman, for her part, finds it strange that Twain was unable to recognize the impossibility of separating the pseudo-tragic narrative of Pudd’nhead Wilson from the pseudo-comic one of the Capello twins, especially considering his deep understanding of societal contingency and his doubts about individual agency.17 The illustrators for Pudd’nhead Wilson also seemed to be unable to reconcile Twain’s turn to the grotesque with their expectations of the comic, humorous Twain. Louis Loeb drew the illustrations for the initial serialization of the novel in the genteel Century magazine, while E. W. Kemble, who had earlier illustrated The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and was generally known for his comical drawings of “pickanninnies” and “plantation types,” drew the illustrations that appeared in the 1899 edition published by Twain’s own American Publishing Company. Both appear literally unable to draw Roxy, choosing to depict her, when she is depicted at all, in the shadows or behind other characters, her features, especially her hair, obscured by her clothing (see figure 1.1). Both Twain and his illustrators display their desire to maintain the fixed differences and racialized distinctions that comedy heretofore had depended on—and their inability to do so.

Gillman relates how Twain described, in his notebooks, a dream in which he is invited to share a pie with a black woman, an act that “disgusts” him yet also elicits fantasies of sexual union and the sharing and mixing together of bodily fluids.18 Perhaps Roxy is the fictional analogue of Twain’s dream mistress-wife, the literary manifestation of Twain’s latent fascination with racial mixing and his anxieties about his own unified subjectivity. Twain was not alone in his anxious fascination with the grotesque; James Goodwin notes that “in the early decades of nineteenth-century American literature the grotesque is commonly invoked through the presence of strange, misshapen, or intimidating forms, and these in turn often reflect anxiety over an encounter with ‘foreign’ or ‘alien’ elements.” These “elements,” he writes, ranged from “Native Americans, black slaves, Italians, the Dutch, and Turks to untracked nature, mysterious strangers, Catholic icons, masquerade disguises, and political spies.”19

Figure 1.1. Roxy’s head, obscured by a headscarf, peeks out from the shadows behind three of the other Driscoll servants. E. W. Kemble, Roxy Harvesting Among the Kitchens, Pudd’nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins, vol. 14 of the Authorized Works of Mark Twain (American Publishing Company, 1908), frontispiece. This illustration also appeared in the 1899 Harper and Brothers edition, and was used as the frontispiece for the 1922 “Authorized Edition” published by Collier’s.

Elsewhere, however, many found opportunities for amusement in the conundrum of identity and differentiation. In Techniques of the Observer, Jonathan Crary describes children’s games and optical toys that engaged the playful possibilities of twinning, doubling, and attempts at differentiation. The thaumatrope, for example, presented two different images: a bird and a cage, for instance—or a man’s face and a lion’s body. Each image would be applied to one side of a paper disk; strings attached on either side, when twisted and then pulled taut, would spin the disk, whirling two images together into one. (Alternately, the disk could be mounted on a vertical stick, which could be spun by quickly rubbing it between the hands.) The stereoscope, in contrast, presented two similar photographs, usually of the same scene but taken from slightly different vantage points. The two photographs would be placed in a viewer that would allow each eye to see one, but not both, of the images. Through the process of binocular vision, the viewer’s eyes would combine the two separate images into a single, seemingly three-dimensional one. The fascination with the stereoscope, Crary writes, comes from the viewer’s simultaneous knowledge that he or she “perceives with each eye a different image,” yet is seeing it “as single or unitary”; one becomes increasingly conscious of the imaginative and even muscular effort required, moreover, the closer one gets to the perceived object(s).20 (The phenomenon of binocular vision continues to amuse, in the form of the View-Master as well as in 3-D projection). These optical toys illustrated the merger between the crisis of vision and national perception in the United States at the end of the nineteenth century. Jennifer Greenhill describes a children’s game called Sliced Nations, where players were challenged to reassemble national types from their sliced-up bodies—and names—suggesting simultaneously that people of different nationalities and ethnicities could be made whole and also endlessly combined (see figure 1.2).21

The popular press, too, played with notions of duality, replication, and identity. A hallmark of the New York World’s feature pages and Sunday magazine, for example, was the article informing readers of ways to identify criminals, the insane, or, in contrast, the rich or the intell...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Comic Sensibility

- Chapter One: The Comic Grotesque

- Chapter Two: Rising from the Gutter

- Chapter Three: Illustration and the Narrative Quality of Appeal

- Chapter Four: The Black Comic Sensibility

- Coda

- Notes

- Works Consulted

- About the Author