- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Human Drug Metabolism

About this book

Provides a timely update to a key textbook on human drug metabolism

The third edition of this comprehensive book covers basic concepts of teaching drug metabolism, starting from extreme clinical consequences to systems and mechanisms and toxicity. It provides an invaluable introduction to the core areas of pharmacology and examines recent progress and advances in this fast moving field and its clinical impact.

Human Drug Metabolism, 3rd Edition begins by covering basic concepts such as clearance and bioavailability, and looks at the evolution of biotransformation, and how drugs fit into this carefully managed biological environment. More information on how cytochrome P450s function and how they are modulated at the sub-cellular level is offered in this new edition. The book also introduces helpful concepts for those struggling with the relationship of pharmacology to physiology, as well as the inhibition of biotransformational activity. Recent advances in knowledge of a number of other metabolizing systems are covered, including glucuronidation and sulphation, along with the main drug transporters. Also, themes from the last edition are developed in an attempt to chart the progress of personalized medicine from concepts towards practical inclusion in routine therapeutics. The last chapter focuses on our understanding of how and why drugs injure us, both in predictable and unpredictable ways. Appendix A highlights some practical approaches employed in both drug metabolism research and drug discovery, whilst Appendix B outlines the metabolism of some drugs of abuse. Appendix C advises on formal examination preparation and Appendix D lists some substrates, inducers and inhibitors of the major human cytochrome P450s.

- Fully updated to reflect advances in the scientific field of drug metabolism and its clinical impact

- Reflects refinements in the author's teaching method, particularly with respect to helping students understand biological systems and how they operate

- Illustrates the growing relationship between drug metabolism and personalized medicine

- Includes recent developments in drug discovery, genomics, and stem cell technologies

Human Drug Metabolism, 3rd Edition is an excellent book for advanced undergraduate and graduate students in molecular biology, biochemistry, pharmacology, pharmacy, and toxicology. It will also appeal to professionals interested in an introduction to this field, or who want to learn more about these bench-to-bedside topics to apply it to their practice.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

Introduction

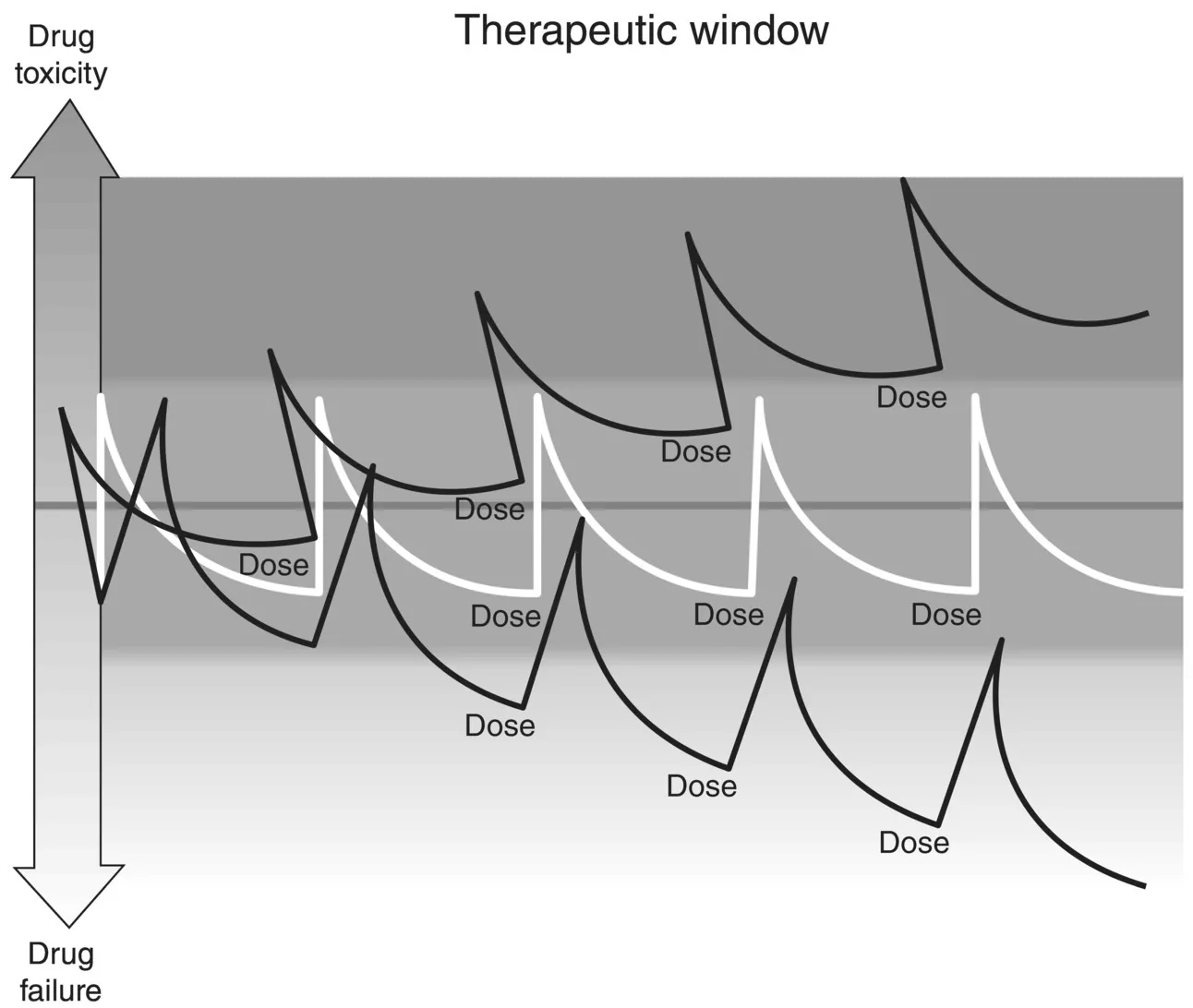

1.1 Therapeutic window

1.1.1 Introduction

1.1.2 Therapeutic index

1.1.3 Changes in dosage

1.1.4 Changes in rate of removal

1.2 Consequences of drug concentration changes

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Drug Biotransformational Systems – Origins and Aims

- 3 How Oxidative Systems Metabolise Substrates

- 4 Induction of Cytochrome P450 Systems

- 5 Cytochrome P450 Inhibition

- 6 Conjugation and Transport Processes

- 7 Factors Affecting Drug Metabolism

- 8 Role of Metabolism in Drug Toxicity

- Appendix A: Appendix ADrug Metabolism in Drug DiscoveryDrug Metabolism in Drug Discovery

- Appendix B: Appendix BMetabolism of Major Illicit DrugsMetabolism of Major Illicit Drugs

- Appendix C: Appendix CExamination TechniquesExamination Techniques

- Appendix D: Appendix DSummary of Major CYP Isoforms and Their Substrates, Inhibitors, and InducersSummary of Major CYP Isoforms and Their Substrates, Inhibitors, and Inducers

- Index

- End User License Agreement