![]()

1 Clubscapes

Poised urgency, wonder, and vulnerability still haunt the twenty-one songs of the double LP Clube da Esquina forty-eight years after its appearance in record stores in March 1972. Initially dismissed by many in the Brazilian music press for its elevation of rock and jazz above Brazilian styles, the collaborative recording led by Milton Nascimento (b. 1942, Rio de Janeiro) and Lô Borges (Salomão Borges Filho, b. 1952, Belo Horizonte) gradually gained international recognition as one of the country’s greatest post–bossa nova albums. The collection is sung in Portuguese save for one song’s use of Spanish and was recorded in Rio’s Odeon studios, making miraculous use of a two-track recording console, an unheard-of limitation at the time. Like Milton and Lô, many of the musicians and poets comprising the collective also known as the Clube da Esquina (referred to throughout as the Clube) have roots in the state of Minas Gerais, and came of age in the modern, provincial grit of its capital, Belo Horizonte (“Beautiful Horizon,” also BH, pronounced beagá [bay-ah-gah]). The first cited use of “Clube da Esquina” to describe the collective was by Milton three years after the LP’s release, in a November 1975 Veja magazine interview and review of his Minas album by critic Tárik de Souza.1 Conceived, recorded, and released during the dark years of Brazil’s right-wing military dictatorship, Clube da Esquina navigated censorship while balancing love songs, atmospheric ballads, and rock tunes imbued with imperatives of resistance, hope, and existential introspection. The music remains stubbornly relevant in the twenty-first century due, in part, to its powerful, thoughtful tone, stylistic diversity, and social justice themes. From among the explorational jazz and rock flavors, coded protest anthems, and sonic meditations, many fans were left still wanting to hear even more from the double LP, perhaps explaining Milton’s 1978 Clube da Esquina II, also a double EMI-Odeon album.

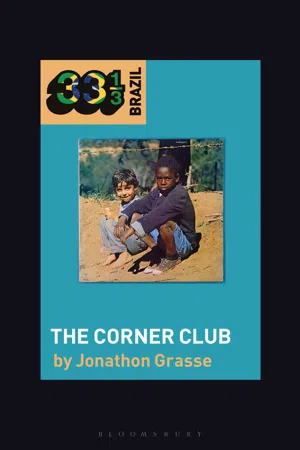

The album cover stares back at the world. I have always been touched by its simplicity and heartwarming innocence, and have gazed back, perhaps naively looking for some type of Brazilian essence in the faces of those two anonymous kids, and in the bands of yellow dirt and green foliage in the background. The rural image, resonating with the scenes I have grown familiar with in the Minas Gerais countryside, was, like the music of Clube da Esquina, effortlessly absorbed into my memories, ideas, and consciousness of Brazil. Fans did not just listen to the album. They looked at the intriguing artwork on the CD’s booklet and gatefold. Weaving through the album’s graphic maze are places and histories of a partially visible concept album about friendship and family, of meditations on identities of place. The Clube collective embraced the local and regional as they simultaneously faced outward to the world, and as Milton shared, these artistic visions were for everyone:

I think that the Club did not belong to a corner, to a group, to a city, but rather to those who, in the most distant part of the world, hear our voices and join us. Clube da Esquina is still alive in the songs, in the lyrics, in our love, our children and who else comes.2

For this author, listening to Tavinho Moura’s LP Como Vai Minha Aldeia (How Are You My Village) during my first visit to Belo Horizonte in 1987 led to one seemingly unrelated musical discovery after another. A few months later, in California’s southern Salinas Valley driving an isolated stretch of Highway 101 in search of San Lucas, I heard Lô Borges’s music for the first time, on cassette. Milton Nascimento’s voice and compositions began looming among these and other discoveries, such as Toninho Horta’s guitar playing (live in Belo Horizonte and at Kimbal’s jazz club in San Francisco). My small collection of their recordings grew with accompanying fascination, full of compelling compositions, expressive guitar playing and musicianship, and evocative voices. Each subsequent visit to Minas (too many to count), the Milton Nascimento concerts in Berkeley with thousands of fans passionately singing along, and snippets of news and information about what I began to discover as the Clube da Esquina collective, all added up to something bigger than these separate elements.

Clube da Esquina’s aesthetics, creative process, and broad musical pallet at times leave the orbit of early MPB (Música Popular Brasileira, Popular Brazilian Music), an acronym ascribed to a broad range of recording artists and repertoire emerging from nearly a half-century’s worth of Brazil’s great, eclectic performers beginning in the mid-1960s. Not a style, the meanings and uses of the MPB label have changed over time, claiming the best of what politically conscious Brazilian youth heard during the 1960s, 1970s, and after. The acronym has been misused as a default category for any Brazilian popular music (the least useful application), including repertoire lacking special connotations of identity and social meaning. Early MPB included a wide swath of Brazilian styles embracing samba, bossa nova, and pop, while, as Carlos Sandroni suggests, acting at times as a “national defense” initially resisting electric rock and other foreign influences. In this sense, MPB emerged for some in proximity to a critical position in which previous generations had placed folk-influenced popular music, and while broadening in the late 1960s to include international sounds and styles, MPB became, as Sandroni states, a “password of cultural-political identification” for Brazilian youth.3 The epic, eclectic Clube da Esquina sounds even more rock oriented and international in scope than the MPB that emerged before, with some of Milton’s compositions in particular also revealing structural complexities and idiosyncratic syntheses of styles never before heard in popular music.

This is one context in which the album sounded less mainstream Brazilian to those looking for bossa nova and samba, and yet attractive to certain MPB audiences yearning for new stylistic and political directions in the early 1970s. In focusing on the album’s eclectic internationalism, a nationalistic reception critical of rock overlooked what others recognized as Clube da Esquina’s salient Brazilian-ness, its rich representations of both rurality and modernity, and a music mixing jazz and rock styles in support of the powerful and sensuous vocal talents found in Milton’s orations and Lô’s youthful coolness. In the global marketplace years later, records like Clube da Esquina were joined with those of other international popular music stars in the music industry’s creation of the catchall “World Music” category, conjured in the late 1980s to promote myriad genres and styles of global popular music. EMI’s 1993 reissue of Clube da Esquina on their newly minted world music-oriented Hemispheres imprint helped to create one of the largest such catalogs at that time.

Referred to as post–bossa nova, the album likewise follows, and contrasts, the psychedelic confrontation and theatrical inventiveness of Tropicália, a short-lived yet highly influential movement of the late 1960s characterized by cofounder Caetano Veloso as a carnivalization of debauchery and scandal—in comparison to what he later described as the Clube’s “seriousness of intentions and sincerity of tone.”4 Clube da Esquina is also post-tropicalist. In addition to Veloso, a core of artists from Salvador, Bahia, grupo baiano (the group from Bahia), including Gilberto Gil, Tom Zé, Gal Costa, and the poets Torquato Neto and José Carlos Capinan, regrouped in São Paulo where they were joined by vanguard rock trio Os Mutantes members Rita Lee, Arnaldo Baptista, and Sérgio Dias. Tropicália musicians established innovative music directions with fusions of rock, pop, and traditional Brazilian popular music, and as a movement did much of the heavy lifting in removing barriers between genres, revolutionizing Brazilian popular music by freely incorporating diverse sounds and occasionally provoking audiences with kitsch, ironic juxtaposition of styles, and calculated mal gosto (bad taste) pointed at conservative society. Tropicália’s energizing music and notable media exposure engaged an increasingly politicized counterculture at a time when the dictatorship turned toward authoritarianism and censorship. MPB and Tropicália in the years leading to Clube da Esquina intertwined with televised song festivals, a popular nationwide phenomenon that bolstered Brazilian popular music’s freedom to explore both traditional and international music while deploying veiled confrontational stances against the dictatorship. Paulo Henriques Britto suggests that Brazil’s politicized counterculture inspired and initiated by MPB and Tropicália emerged slowly, and on a large scale only as a post-tropicalist phenomenon in the early 1970s.5 National political conflict marked the four years between the coalescence of Tropicália in 1968 and the Clube da Esquina LP, a period that witnessed a worsening of authoritarianism that would directly engage the lives of Clube artists, and provided grist for the album’s protest songs. As a post-tropicalist phenomenon, the Clube echoes some of Pedro Duarte’s characterizations of the Tropicalístas, who were also a collective.

They disputed the prevailing order, not only of institutional politics but also of moral conservatism. . . . They intended to make art the spearhead of life transformations. . . . We find in Brazilian Tropicalism three aspects that, since German Romanticism, have characterized modern avant-garde movements: collective production, artistic innovation, and cultural criticism.6

In their own post-tropicalist manner, the Clube associated themselves with trends in cinema, literature, poetry, philosophy, and photography, with roots in these influences going back to the pre-Tropicalist early 1960s. Comparing the two collectives, Paulo Thiago de Mello emphasizes the pop culture epicenter of Tropicália’s manifesto-based movement in contrast to the Clube’s intuitively derived collaboration.7 Belo Horizonte–based musician, songwriter, and producer Chico Amaral suggests the expressive tensions behind Tropicália’s rhetorical stances such as the juxtaposing of low and high art, and foreign rock versus homegrown bossa nova, were approached “musically” by the Clube’s distinct contributors whose influences were equally broad.8 Holly Holmes addresses another comparative aspect by noting how “[Milton’s] music sounded the rural landscapes of Minas Gerais as much as the Tropicalístas sounded urban pop culture,”9 with rural/urban distinctions forming important processes in Brazilian popular culture’s twentieth-century transformations of folk music, as in the case of samba, with its origins in regional, rural dance culture, becoming a nationally recognized popular urban form. Marcos Napolitano arguably locates the Clube position in his description of Milton’s rise in 1967, indirectly marking Clube da Esquina’s impact following its release:

Milton brought new sounds and poetic materials to MPB: complex harmonizations sustaining subtle and delicate melodies; traditions of the regional music of Minas Gerais, allied to a certain reminiscence (melodies and ornaments) of the sacred music of Minas Gerais. This material was influenced by the most recent international music (which, in Milton’s case, were very eclectic, absorbing jazz currents) . . . his poetic partners . . . broke away from forceful, epic tone and linear narrative, in favor of an intimate poetic perspective, structured in freer meter.10

Clube da Esquina finds inspired meditations on the nature of being Brazilian, fresh processes of musical and poetic creativity, and universal themes of citizenship, belonging, and friendship. Found also are rebellion, contradiction, and the rejection of outdated stereotypes of both Brazil and Minas Gerais. As a 1972 LP, as a collective, and arguably as an informal regional movement, the Clube da Esquina phenomenon engages cultural significance overlapping with, and running parallel to, MPB and Tropicália sensibilities while saying something entirely new. The album launched and furthered careers of over a dozen musicians and lyricists on whom the collaboration’s success relied, though the participants never formed nor maintained themselves as a distinct band. Symbolic of a neighborhood street intersection in Belo Horizonte, the “club” is this collective, whose music surfaced from a deep pool of talent and tastes, and not only from the dual artistic vision of songwriters Milton Nascimento and Lô Borges named on the album’s back cover. Some of that depth of talent began with the innovative Rio-based band Som Imaginário (Imaginary Sound), held together by Milton’s childhood friend and lifelong collaborator Wagner Tiso. All but two Clube da Esquina songs feature one of three lyricists: Fernando Brant, Lô’s brother Márcio Borges, and the Rio de Janeiro native Ronaldo Bastos. The record’s primary personnel include musicians emerging from Belo Horizonte, then a city more or less off of Brazil’s popular culture radar: Lô’s friend Beto Guedes (electric bass, electric guitar, twelve-string guitar, vocals, and percussion); Rubinho (d rums and percussion); guitarist Toninho Horta (also vocals, electric bass, and percussion); guitarist Tavito (also of Som Imaginário); and Nelson Ângelo (electric guitar, piano, and percussion). No two songs on the album have the same lineup of musicians.

Understanding the album’s Minas Gerais connections, and those to the creative environs of Belo Horizonte, provides an appreciation beyond its surface sensuality and inviting glow. Yet Milton and other Clube members were known to reject suggestions that Clube da Esquina was merely a regionalist product, or that the work represented only that of a group of mineiros (residents of Minas Gerais).11 The occasional downplaying of regionalist identity in the album and collective likely spoke to a fear of critics and the public belittling mineiro culture as being provincial and less sophisticated than that of Rio or São Paulo. This notion of negating the regionalist label is perhaps underscored by the fact that Milton, Wagner, and others of the collective had left BH for Rio years before making Clube da Esquina. Milton eked out a living in São Paulo during 1965–66 before shooting out into the world as a song festival winner with A&M and Codil record deals. None of Clube da Esquina tracks are specifically about Minas Gerais, and the place is mentioned neither in a lyric nor in print anywhere on the album. Despite the full bleed cover photo’s compelling suggestion of Milton and Lô in a fictive, rural Minas Gerais childhood, the shot of two anonymous kids was taken in the Rio de Janeiro countryside. What might be seen as a tension over the representation of a rustic Minas in Brazil’s modern world of bossa nova and industrialization adds to the album’s mystery. Holly Holmes points out that when referenced as regional, the work of the Clube is typically characterized as música mineira (music from Minas Gerais) rather than music from Belo Horizonte, emphasizing the broader scope of cultural symbolism associated with the entire region, and the gloss of rurality and rusticity over urban grit.12

Regional themes, however, poured from earlier efforts by the proto-collective since Milton’s first television appearance in 1967: Brazil already knew him and some of his musical friends as mineiros, and Clube da Esquina followed embryonic stages of previous albums and songs with a strong regional identity.13 The collective’s work after 1972, particularly Milton’s, includes direct, strong programmatic representations of Minas Gerais and its capital of Belo Horizonte as a set of unique cultural territories. Milton’s successful EMI-Odeon LPs Minas (1975) and, using an archaic spelling, Geraes (1976), the latter featuring a song titled “Minas Geraes” by Clube members Novelli (Djair de Barros e Silva) and poet Ronaldo Bastos, remain clear evidence of programmatically regional projects. The collective’s earliest phase is more strongly associated with MPB, further colored by bossa nova’s symbiosis with Milton’s innovative stylistic directions, his supporting musicians, and influential music arrangers. ...