![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE PREINDUSTRIAL CITY

Before the Civil War … the better classes were very particular with whom they associated; … the leveling principle was not tolerated; but where worth was found it was always recognized.

—planter’s son J. B. Alexander

PRIOR TO ITS New South industrial awakening, Charlotte functioned quietly for more than a century as an agricultural trading village, the courthouse town for Mecklenburg County. The difficult geography of the Carolina “backcountry” meant that Mecklenburg possessed few of the sprawling plantations of Old South lore. Nonetheless, the county’s larger landowners securely controlled economic and political life, and they expected deference from the rest of society. The hamlet the planters built at the county’s center reflected this society both in its process of city planning and in its arrangement of dwellings and shops. In the 1850s the construction of railroads would set Charlotte apart from surrounding backcountry towns and put it on the road to prosperity. This commercial growth, however, would do little initially to disrupt either traditional social patterns or urban forms.

TRADING HAMLET, 1750S–1850S

Charlotte’s first white settlers arrived in 1753, choosing a hilltop site where two Native American trading paths crossed.1 The Catawba River flowed a few miles away but the newcomers paid it little mind. Charlotte lay in the Carolina piedmont region, the band of rolling hills betwixt the Appalachian mountains to the west and the flat coastal plain along the Atlantic to the east. In the piedmont, frequent waterfalls and rocky rapids made rivers mostly unusable for transportation. Instead, the settlers followed the example of the Catawba Indians before them and did their trading overland via the old native trail southward to the port of Charleston (still in use as Interstate 77) or the Great Trading Path that ran northwest into Virginia (Interstate 85 today).2 To better attract the commerce of surrounding farmers, the settlers pushed for designation as the county seat. They named their village in honor of England’s Queen Charlotte, promised to call the county after her birthplace of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Germany, and for good measure designated their main thoroughfare Tryon Street to flatter the colonial governor. Governor William Tryon granted the community its wish, signing Charlotte’s official city charter as a courthouse town in 1768.3

By the time of the American Revolution, Mecklenburg County already was growing and processing enough corn and wheat to make it a military objective in the southern campaign of British general Lord Cornwallis. “The mills in its neighborhood were supposed of significant consequence,” wrote a British officer, “to render it for the present an eligible position, and in the future a necessary post when the army advanced.”4 Cornwallis captured Charlotte and made it his base of operations but found little welcome from the local populace.5 As early as 1775 Mecklenburgers had defiantly published a document called the Mecklenburg Resolves, which declared all royal commissions “null and void” and urged citizens to elect military officers “independent of Great Britain.” They had even—local tradition holds—signed a Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence a year before the United States officially broke with Britain.6 “The counties of Mecklenburg and Roban [neighboring Rowan] were more hostile to England than any in America,” a British veteran of the southern campaign later remembered.7 With British troops suffering harassment at Charlotte and defeat at the nearby Battle of Kings Mountain, Lord Cornwallis retreated, muttering that Mecklenburg was a “hornets’ nest of insurrection.”8 Charlotte citizens proudly adopted “the Hornets’ Nest” as their village’s nickname.

In the generation following the Revolution, corn and wheat production continued to drive the economy, along with two new products of the land, cotton and gold. The gold strike came in 1799 when a farm boy playing in a creek twenty-five miles east lugged home a glittering seventeen-pound nugget.9 Charlotte, the closest well-established town, now became the trade center for America’s first gold-producing region. The city experienced no wild gold rush, but it did draw miners from as far as Europe, who sank shafts literally under Charlotte streets as well as across the surrounding countryside. To handle the wealth, a branch of the North Carolina State Bank opened in 1834, the town’s first such institution.10 In 1837 an imposing U.S. Branch Mint went up at the corner of Mint and Trade Streets, coining $1.6 million in gold pieces within a decade.11 The mining bubble burst in 1849, however. Much richer discoveries in California eclipsed the Carolina deposits, and miners streamed westward in that now-legendary rush. Charlotte settled back into its agricultural ways.

The arrival of cotton farming meant more to Mecklenburg’s long-term growth than did the discovery of gold. In 1793 American inventor Eli Whitney created the cotton gin, which allowed cotton to be farmed economically for the first time across much of the South. The new crop made its most dramatic impact in the coastal plain, where good river transportation enabled farmers to create huge plantations producing the fleecy staple. But cotton also found its way into the backcountry, taking hold particularly in the productive soils of Mecklenburg and a handful of adjoining counties in the Carolina piedmont. As early as 1802 Mecklenburg County led the entire state of North Carolina in number of cotton gins.12 The enumerator for the 1810 U.S. census confirmed the county’s impressively high output: “103 cotton gins … 3512 bags of cotton … Each bag about 250 wt. … and all sent to market principally Charleston, South Carolina.”13

The offhand phrase, “all sent to market principally Charleston,” made cotton selling sound simple. In fact it was anything but easy for Mecklenburg residents to get their crop to market, and that reality decisively shaped the nature of farming in the county. Farmers had to pile their cotton in wagons, then haul it southward along rutted dirt paths eighty miles or more to the nearest river port. At the fall line towns of Columbia, Camden, or Cheraw in South Carolina, they transferred the cotton to boats for the journey to Charleston. “All know what it costs to take a load of cotton to the nearest market,” complained the Charlotte Journal in 1845. “It generally takes from 6 to 8 days—this at $3 per day would be at lowest calculation $18 to get a load of cotton to market, which at the present price of the article makes a great inroad into the amount received.”14

The arduous journey to market meant that the backcountry had a structure of opportunity much different from that of the coastal plantation belt.15 For lowcountry agriculturalists, a simple formula of “more land, more slaves, more cotton” seemed the surefire strategy to wealth. Historians consider twenty slaves and a hundred acres of cultivated land the minimum for a “plantation,” but many planters in the coastal Carolinas amassed far more. It was not unusual to find lowcountry plantations with more than 200 slaves and thousands of acres of cotton fields, controlled from white-columned mansions or elegant Charleston townhouses.16 In the backcountry, things were less simple. Because of the “great inroad” that difficult transportation made on profits, backcountry farmers could not rely on a single cash crop. Instead of concentrating on cotton, they found they had to raise a mix of crops, calculating what might bring a profit if cotton prices should drop too low to cover transportation costs. The same census taker who noted all the cotton flowing out of Mecklenburg County in 1810 also remarked on the high wheat and corn production. The county had twenty-one grist mills, plus a whopping sixty-two stills, corn liquor being the most efficient form in which to transport the yellow grain to the docks at Charleston.17 By the 1850s Mecklenburg stood near the top of North Carolina agriculture in nearly every crop except tobacco.18 Among the state’s seventy-five counties, Mecklenburg placed third in cotton output, fourth in butter, eleventh in corn, and twelfth in wheat production—despite ranking only twentieth in population. At the same time Mecklenburg stood far ahead of coastal plantation counties in dollars invested in farm machinery, a testament to the way that the lack of an easy cash crop pushed backcountry individuals to innovate.

This structure of opportunity shaped Mecklenburg’s society as well. In contrast to lowcountry counties, only a single farmer here on the eve of the Civil War possessed as many as fifty slaves.19 Those few men who owned twenty slaves and thus qualified as planters usually also kept a store in town, practiced law or medicine, or pursued other nonfarm endeavors as a hedge against agricultural uncertainty. While big planters were relatively scarce in Mecklenburg, the county’s fertile soil helped make smaller slaveholders unusually numerous. More than 800 households owned between one and twenty laborers, putting Mecklenburg near the top of North Carolina counties in this category. This situation boded well for town development. In the lowcountry, big plantation owners traded directly with brokers in Charleston or Wilmington and often simply ignored local towns. Mecklenburg’s smaller slaveholders, by contrast, could seldom muster the time, expertise, or economic clout to deal directly with the coast and instead traded their crops to Charlotte storekeepers.

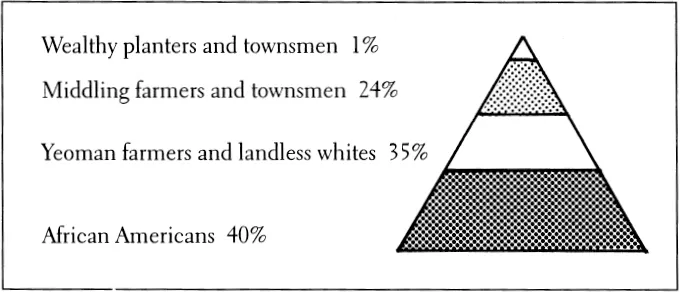

Having few planters and many small slaveholders did not make Mecklenburg a society of equals. Rather, the social structure resembled a pyramid, narrow at the peak and broad at the base. At the pinnacle stood the planters, less than 1 percent of Mecklenburg families.20 Just below them came the merchants and smaller farmers who owned fewer than twenty slaves. Taken together, all these slaveholders made up a distinct minority of the county, roughly a quarter of the total population. Nonslaveholding whites occupied the next level of the pyramid, around 35 percent of county residents. At the bottom of the pyramid stood African Americans, whose labor made cash-crop agriculture profitable. From just 14 percent of Mecklenburg population in 1790, the number of slaves increased steadily with the rise of cotton farming until, by the 1850s, they comprised fully 40 percent of the county’s inhabitants.21

Social and political power rested firmly at the top of the pyramid. Mecklenburg held to traditional ideas of social organization that historians have often noted in early agricultural America.22 The family rather than the individual constituted the basic unit of society, and all members within a family were expected to defer to its senior or most able male. This family model of deference extended to the community. The most able family heads—those who amassed sizable amounts of property—controlled community affairs. Men who owned no land held only limited voting rights (women and other “dependents” possessed no voting rights at all). Community leaders thus came almost entirely from the wealthiest strata of society, and unless they proved notably rude or incompetent, they could expect to enjoy deference from their lesser fellows. As a leading historian has written of George Washington’s Virginia,

FIG. 6. MECKLENBURG’S SOCIAL PYRAMID

Before the Civil War Mecklenburg society resembled a pyramid with a small number of slaveholders at the top. Slaveowners made up only a quarter of the county’s population, but that minority held considerable power over the society as a whole.

The overwhelming majority of men were agriculturalists, differing in the scale of their operations more than in the nature of them. … Nearly every [elected official] was a representative of agriculture; there was little else in Virginia he could represent. Under these circumstances, those who achieved most in nonpolitical life could be vested with political power without seriously endangering the interests of less successful men. It was more or less appropriate for the large planter to represent the small farmer, and the farmer accepted this leadership as natural and proper.23

By today’s standards Mecklenburg before the Civil War was far from a democracy. Women, of course, could not cast ballots, nor could African Americans, not even the handful of free blacks.24 Even among white men the vote was strictly limited.25 Only men owning substantial amounts of land could participate fully in government. Well into the 1850s North Carolina law prohibited those with less than fifty acres—more than half the white population—from voting in senatorial elections. Men who wished to run for office faced much stiffer property requirements, from 100 acres for a seat in the state legislature to several hundred acres for governor. Even jurors, sitting in judgment at the humblest trial, had to be men of property. For most local offices the governor or state legislature simply appointed officials rather than going to the trouble of holding elections. Not surprisingly they tended to pick men who were landholders like themselves. This was true in Charlotte, where the legislature appointed the first city commissioners, who afterward picked their own successors, and it was true in Mecklenburg County, where most affairs rested in the hands of state-appointed justices of the peace, who typically served for life and enjoyed the informal title “squire,” in open emulation of the English gentry.26

Men of wealth felt at ease in their position atop society before the Civil War. J. B. Alexander, scion of a leading Mecklenburg planter family, later recalled, “A half century ago the better classes were very particular with whom they associated; that is they would not allow their daughters to go riding, or attend social parties, or in any way be thrown together with people of a lower caste.” This “old-time aristocracy,” secure in its control of the ballot box, looked after society’s interests as it saw them. Those who met the elite’s approval might attain admittance to the apex of the pyramid; wrote Alexander, “Where worth was found it was always recognized.” From the general populace, though, Mecklenburg’s “better classes” expected obedience and deference. “Fifty years ago,” Alexander remembered nostalgically, “the leveling principal was not tolerated.”27

RAILROAD TOWN, 1850S–1870S

Despite the prosperity promised by its fertile soil, and despite the willingness of its slaveholders to experiment with crop mix and invest in new machinery, Mecklenburg County faced a frustrating barrier to growth. Geography held the county prisoner. Some cash crops could go out overland, but high transportation costs meant that most trade remained local and self-contained—nearby farmers meeting at the courthouse square to exchange surplus goods mostly with each other. By the end of the 1840s Charlotte boasted a population of 1,065.28 It was almost exactly the same size as half a dozen other courthouse hamlets scattered over the Carolina piedmont. Salisbury, Salem, Greenwood, Abbeville, Greenville, and Spartanburg each performed similar functions f...