![]()

1

Griffith and Mother Ireland

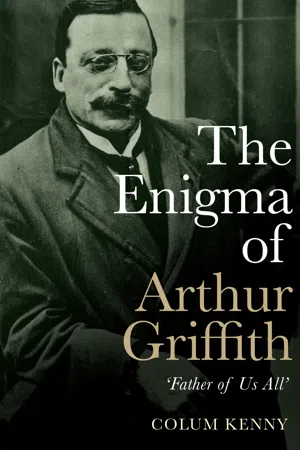

Arthur Griffith was ‘an enigma’, mysterious or difficult to understand, wrote his contemporary James Stephens. He was ‘the father and the founder’ of Sinn Féin, John Dillon MP informed the House of Commons in 1916.1

A photograph of Griffith taken in London during the treaty talks in late 1921, but published by The New York Times in 1922 above the caption ‘Head of the Irish Free State’ is a reminder of his resilience (Plate 1), – until civil war finally undid him.

Harry Boland, who fought against Griffith’s side in that civil war and who died just eleven days before him, is purported to have said of Griffith to a friend, ‘Damn it, Pat, hasn’t he made us all?’2 The first prime minister of the Irish Free State, W.T. Cosgrave, declared in 1925 that Michael Collins could but say ‘Griffith was the greatest man of his age, the father of us all.’3

Griffith was a politician and thinker, a cultural and economic analyst. Yet when the French journalist Simone Téry met him in Dublin in the summer of 1921, she remarked: ‘With his broad-shoulders, square fists and square face, Arthur Griffith looks more like a manual worker than an intellectual.’4

He was one of the founding fathers of the Irish state, if not indeed the founding father. It took courage and judgement for him to sign the articles of agreement for an Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921. Doing so after him, Michael Collins said that he had signed his own death warrant. Assessing Griffith – warts and all – tells us something about ourselves. For, like him or not, he shaped the political framework of modern Ireland. When he died, his devastated and loving widow Mollie bitterly described him as having been ‘a fool giving his all, others having the benefit’.5

James Joyce sought his advice when trying to get Dubliners published, and Griffith gave W.B. Yeats both paternal guidance and what John Hutchinson has described in his study of the Gaelic Revival as ‘invaluable’ aid.6 Joyce and Yeats had complex relationships with their own fathers, who were not very practical.7 Griffith’s helpful dealings with these men merit closer attention than they have received to date, and they are explored in this volume. Yeats has a reputation that sometimes seems to depend on diminishing Griffith, and Joyce cannot be fully appreciated if his interest in Griffith’s politics and his respect for Griffith’s journalism overall is discounted.

In the Dublin societies to which he belonged when young, Griffith’s friends loved him. They went rambling and cycling in the country. They swam naked at ‘The Forty Foot’ in Sandycove, sun-bathing nearby on the hidden roof of an old Martello Tower. James Joyce also visited that tower and located there the opening scene of his novel Ulysses (Plate 6). The era of Joyce’s Ulysses, set in 1904 but not published until 1922, was also that of Griffith. What is it about this shy, hard-working nationalist, who enjoyed a quiet glass of stout with his friends and delighted in street songs, that irks some people and can find him begrudged a generous mention on commemorative occasions?

This book will take a fresh look at Griffith’s life from its humble beginnings to its sudden end, and in the context of his relations with Maud Gonne, James Connolly, Éamon de Valera, James Joyce and W.B. Yeats, among others. His creation of Sinn Féin, his leadership of the treaty negotations in London and his presidency of Dáil Éireann are traced through exciting and disturbing developments of his day. But we also see Griffith the man, father and father figure, who whistled and sang ballads and arias; who was an influential journalist and a loyal friend and husband. Darker issues are also addressed, including Irish anti-Semitism and racism.

Politic Words

One morning recently, in the hushed surrounds of Ireland’s National Library where Griffith liked to read, I met someone suspicious of Griffith even yet. The man was struggling with a microfilm and requested my help. He informed me, in a strong Ulster accent, that he was trying to access back issues of The Freeman’s Journal. He asked me what I was researching and I told him. ‘Ah’, he said, giving me a certain look. ‘Some people didn’t like Griffith’. Then, ‘He signed The Treaty’ and ‘he wasn’t a republican’. I did not ask my neighbour to define ‘republican’.

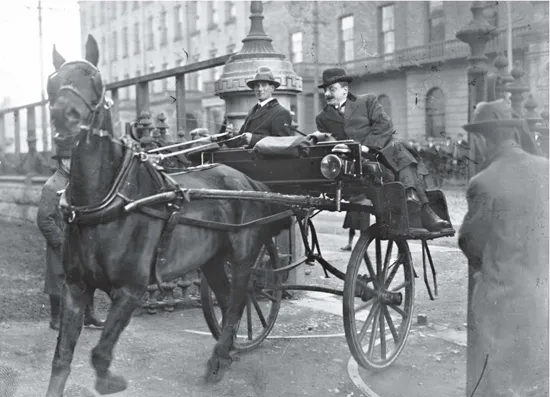

Griffith arrives at Earlsfort Terrace for Dáil Éireann’s treaty debate in December 1921 (National Library of Ireland (INDH386]).

‘Arthur Griffith, as the world knows, was the father of Sinn Féin,’ said Griffith’s acquaintance Kevin O’Shiel.8 Yet the notion that Griffith somehow let down a victorious struggle of which he disapproved, or that the treaty that he signed was to blame for partition, gained traction following his sudden death in 1922. This is despite the fact that partition was already a reality when negotiations for a treaty began. The parliament of Northern Ireland had opened. It was axiomatic that the Irish went to London to make concessions in return for concessions. An unbending demand for the political unity of the island of Ireland as a republic would not succeed where military action had already failed. It was not partition itself, nor the continuing use of some Irish ports by the British navy, but the form of oath prescribed for members of the new Dáil and the nature of the new state’s future relationship with the Crown that finally led to civil war.

In the early 1900s, Griffith laid out a constructive and principled path to independence and, within twenty years, he and his team agreed treaty terms in London that created the Irish Free State. The signing of those terms in Downing Street was an act of compromise and statesmanship by which they acknowledged that, with independence, came responsibilities. They were subsequently backed by a majority of representatives in Dáil Éireann, and thereafter by a majority of voters in a general election who chose candidates supportive of the treaty. Griffith told the people that the treaty was the basis for further developments: ‘It has no more finality than we are the final generation on the face of the earth.’9

Griffith and his treaty delegation in London engaged in real politics with a United Kingdom government that was itself vulnerable to its own domestic pressures. The emotive and shifting nature of such constitutional negotiations has been clearly evident again during the recent Brexit debates in Britain. Brexit has been a reminder of the great challenges involved in reconciling very different perspectives, both cultural and political. Irish people, then and since, might too easily overlook the difficulties on the British side in 1921. And de Valera’s refusal to attend the crucial negotiations with Prime Minister David Lloyd George from October to December 1921, no matter what his rationale, greatly complicated the challenges involved.

Griffith, like any revolutionary or politician, had both strengths and weaknesses. This book is a critical assessment, not the hagiography of a saint. It will contextualise his occasionally problematic attitudes but not seek to excuse them. Was he ‘narrow’ as some detractors allege? Overall, his voluminous journalism suggests otherwise. However, given how much he wrote and that he did so usually to a tight deadline, it is unsurprising to find that Griffith sometimes penned or printed regrettable statements. He was no perfect Marvel-comic hero. He was a small, limping, lower-middle-class politician with poor eyesight, an unglamourous wife, an aversion to dramatising violence and a tendency to sharp comments. Yet his leadership inspired a generation.

Was Griffith also among those who regarded art or literature ultimately as ‘the scullery maid of politics’? W.B. Yeats used that term dismissively about people whom he distinguished from ‘the men [sic] of letters’ and from those ‘who love literature for her own sake’ (whatever that might mean). It is true that Griffith believed literature should serve purposes other than those of mere entertainment or even speculation. Yet for him the priority of Irish independence by no means precluded art from providing pleasure or enlightenment. While he was strongly critical of The Playboy of the Western World, his antipathy to John Millington Synge has been somewhat exaggerated, and the weekly papers that he edited for twenty years bear eloquent witness to the fact that he was no philistine. In any event, literature is never entirely free of ideological, social or political implications.

Griffith is an awkward father figure, the one who cannot be denied but whose actions and foibles risk exposing characteristics and contradictions in ourselves that we would rather not see. In the case of Yeats, it is instructive to recall the period when that poet was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), and when Griffith boosted Yeats’ career. Yeats later wished to put behind him his former IRB membership but it possibly helped him to win a seat in the senate of the new Irish Free State.10 When considering the dynamics of the relationship between Griffith and Yeats it should be remembered too that both men were closely involved with the dazzling Maud Gonne, a fact that the patrician Yeats turned to his reputational advantage even as the paternal Griffith did not.

Born in the heart of Dublin, Griffith was a hard-working artisan who married late due to his poverty, who then had two children whom he deeply loved. He was ready to compromise, including with unionists, but firm in his resolve that independence was Ireland’s right and that the Irish Free State was a stepping-stone towards greater things. ‘How time has justified the Irish Treaty,’ wrote the ambassador Michael MacWhite to W.T. Cosgrave as the Irish Free State became a republic in 1949. ‘We know now what Griffith meant when he wanted freedom to achieve freedom,’ he added.11 The fact of partition was already a reality when Griffith signed the agreement for a treaty and, contrary to a widespread misunderstanding, was not the immediate cause of de Valera’s resignation as president of a Dáil that then voted to accept the document that Griffith and Collins had signed in London.

Mother Ireland

A constellation of defeat, dependency, despondency and martyrdom – in the face of sometimes brutal imperialism – gave strength over centuries to the myth of Mother Ireland as a poor woman reduced to demanding the self-sacrifice of her sons for an almost hopeless cause. That woman, known as ‘My Dark Rosaleen’, ‘Kathleen Ni Houlihan’, ‘Shan Van Vocht’, ‘Éire/Erin’ etc., was both an object of desire and a pietà, whose beloved children’s blood watered a tree symbolising national regeneration or resurrection. For James Joyce’s Stephen, Ireland was ‘the old sow that eats her farrow’.12 Griffith himself invoked regeneration by using the word ‘resurrection’ in the title of his key 1904 tract on the constitutional and economic salvation of Ireland (The Resurrection of Hungary), while the weekend that rebels chose for the ‘rising’ in 1916 was significantly that of the festival of Christ’s resurrection. In 1917 Yeats wrote of Ireland that ‘There’s nothing but our own red blood can make a right Rose Tree,’ while also expressing dismay that ‘a breath of politic words has withered our Rose Tree’. He was still singing in 1938, as he flirted with fascist ideas:

And yet who knows what’s yet to come?

For Patrick Pearse had said

That in every generation

Must Ireland’s blood be shed.

Griffith preferred ‘politic words’ to bloodshed, regarding them as an art and a democratic necessity rather than a withering disease. Yet, he was no pacifist, for he advocated defensive force and even countenanced attack where it was necessary. In 1914 he attended a key private meeting with Patrick Pearse and other future signatories of the 1916 proclamation and, as will be seen, agreed a broad strategy with them. He participated in the Howth gun-running of 1914 and later drilled dutifully with the rifle that he got there, although he was not at the barricades on Easter Monday 1916. He subsequently became acting president of the provisional government during the War of Independence, when de Valera went to America for eighteen months.

Griffith informed and guided the political consciousness of a cultural revival that had floated on an ocean of sentimental affection for the idea of Mother Ireland, or ‘Erin’ – that poor old woman worn down, but destined to come into her queenly inheritance and be rejuvenated: ‘There was much Kathleen Ni Houlihan, Dark Rosaleen poetry written,’ Mary Colum later remarked somewhat sarcastically of the period.13 Griffith himself was not adverse to idealising Ireland and Irish women when articulating his vision of an Ireland that he hoped would be self-sufficient, while also being less materialistic than England. However, his unifying emphasis was ultimately modern and pragmatic....