- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book offers a multidisciplinary, holistic appraisal of the implications of the UK's withdrawal from the European Union (EU) for tourism and related mobilities. It attempts to look beyond the short- to medium-term consequences of these processes for both the UK and the EU. It is divided into four major sections: Context, Tourism Impacts, Implications, and Global Britain? The volume employs case studies to highlight Brexit's ripple effects on tourism, mobilities and immobilities. It will be of interest to researchers, students and policymakers in tourism, European studies, political geography, regional development, international relations and politics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Brexit and Tourism by Derek Hall,Prof. Derek Hall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Hospitality, Travel & Tourism Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The UK and ‘Europe’

The study of the EU is filled with theories of European integration. Brexit confronts us with the need to theorise European disintegration … [yet] Liberal inter-governmentalism draws in a mix of interests, institutions and ideas to highlight that Britain and the EU (especially Germany, France and other big states) are caught up in a deeply enmeshed set of interdependencies from which there is no easy escape whatever their leaders may want.

Oliver, 2015: 3

1.1 The UK-‘Europe’ Relationship

It is claimed (particularly by British authors) that it was Winston Churchill’s ‘United States of Europe’ speech in 1946 that helped to crystallise thinking towards a time when all Europeans would see themselves as part of a peaceful whole (Danta & Hall, 2000). Certainly, such ideals of a united Europe were the inspiration that led, via the setting up of the Benelux customs union in 1948, to Jean Monnet and Robert Schuman’s 1950 plan for an alliance between France and Germany that established the first instruments of European integration. These were the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), and, most significantly, the European Economic Community (EEC), which came into effect in January 1958.

While the waning empire/colonies persisted through the 1950s, Britain remained aloof from (mainland) European cooperation. And when in 1961 the United Kingdom applied for EEC membership, it was twice vetoed by the French president Charles de Gaulle (in 1963 and 1967), not gaining accession until 1973. Although, or perhaps because of, having sought refuge in England during much of the Second World War, de Gaulle recognised that because the UK had avoided the experience of both wartime occupation and defeat, the country did not appear to embrace those fundamental desires for the sharing of sovereignty with other European peoples that drove Monnet and Schuman. As Clement Attlee put it in 1957, ‘We’re semi-detached’.1

The insular UK tended to be dominated by a drive for mercantilism coupled with a misplaced sense of superiority that is still evident today, perhaps even magnified, in some circles. The Commonwealth, and a perceived ‘special relationship’ with the United States, diffused the country’s priorities.

Hence the focus on the economic aspects of integration that has been common among British politicians and has restricted their ability to play an influential and constructive part in some of the most significant developments … [including t]he EU’s potential contribution to making the world a safer place in fields such as climate change and peacekeeping. (Pinder & Usherwood, 2013: 3)

1.2 The ‘European Process’

While the UK looked on until 1973, a number of complementary bodies were established alongside the EEC to further its goals (Box 1.1).

The main institution’s name has changed over time, to some extent reflecting the evolving nature of its role and objectives. The EEC (also known in the UK as the ‘Common Market’ after a customs union came into effect in 1968), Euratom, and the ECSC combined during the 1980s to form the ‘European Community’ (EC). In 1993 the Community underwent a major re-organisation which subsumed, but did not replace, the EC; the overarching body now becoming the ‘European Union’ (EU).

Box 1.1 Complementary European institutions

European Commission: to handle the bureaucracy involved in running the institution

Council of Ministers: as the main decision-making body with respon-sibility for broad policy formation and implementation, with a Council Presidency rotating every six months

European Parliament: to provide a democratic forum for debate and to operate as a watchdog

European Court of Justice: to hear cases involving member states

European Council: of heads of states meeting at least twice yearly to discuss issues before the Community (and later Union)

Committee of the Regions: to bring local concerns to the attention of the Council.

Most functions have been carried out in Brussels, but with Luxembourg and Strasbourg also as important centres of activity.

The Community set out to work closely with other European organ-isations, such as: Organisation for European Co-operation (later the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: OECD)

North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO, founded 1949)

Western European Union (WEU, 1954)

Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE, 1973).

Sources: Danta and Hall, 2000: 6; Hall et al., 2006: 6.

Two broad courses of action that have characterised the EEC, EC and EU have been those of ‘deepening’ and ‘widening’. ‘Deepening’ (Box 1.2) has involved mechanisms aimed at bringing member countries into closer economic, political, administrative, and security ‘alignment’. Again, it is notable that strong foundations for this were established prior to the UK’s accession.

Box 1.2 Stages of ‘deepening’

Treaty of Paris (1951) established the ECSC

Treaties of Rome (1957) establishing the EEC and Euratom

Common Agricultural Policy (CAP, 1962)Completion of a

Customs Union (1968)

European Council (1975)

European Monetary System (EMS, 1979)

Single European Act (1986), which set the goal of creating a single market by 1993

Schengen Convention (1990) proposed the abolition of internal border controls and a common visa policy, creating the Schengen Area in March 1995. Formally, the agreements and rules adopted were sepa-rate from EC structures as they did not meet with consensus among EC member states.

Treaty on European Union (TEU), also known as the Maastricht Treaty (1993), set the goals of achieving monetary union by 1999; new common economic policies; European citizenship; common foreign and security policy; and common policy on internal security. Indeed, Maastricht’s three main pillars of economic and monetary union (EMU), commitment to a common foreign and security policy (CFSP), and internal security, including trans-border mobility and crime, changed the ‘architecture’ of the Union to which new appli-cants would seek accession.

Treaty of Amsterdam (1997), covering aspects of justice and home affairs.Common monetary policy and single currency, the euro (1999).

Although the Single European Act had marked a decisive shift towards majority voting in the Council, and the Maastricht Treaty transferred some powers to the European Parliament, decision-making remained something of a compromise between inter-governmentalism and cooper-ative federalism.

Sources: Danta and Hall, 2000: 7; Hall et al., 2006: 6–7.

Although set out in the Treaty of Rome, the EU’s ‘four freedoms’,2 covering the free movement of goods, services, capital and people, were extended under the ‘internal market’ rules introduced by the Single European Act. Such freedoms, however, may be seen to be potentially in conflict with the EU’s environmental goals of sustainability.

The 1993 Copenhagen criteria for accession included the development and sustaining of a functioning market economy, the capacity to accommodate competitive pressure and market forces within the Union, the development of democracy, the rule of law, human rights and the protection of minorities, and the ability of countries to accept the obligations of the Union which included some 20,000 laws and regulations of the acquis (Hall, 2017: 31), laws and regulations from which any member foolish enough to consider leaving the EU would need to disentangle themselves.

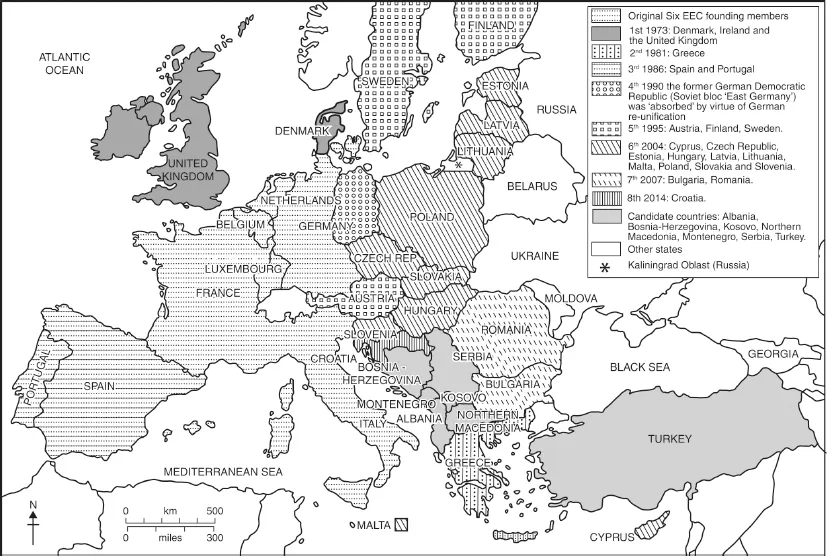

The second goal, ‘widening’ (Figure 1.1), has been pursued through a series of geographical enlargements, although from 1958 until 1973 the EEC consisted solely of the six members of the ECSC: Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg (the former Benelux members), France, Germany and Italy.

Certain ‘holdover’ countries have remained outside the Union for differing reasons. Norway applied for membership in 1962 and negotiations were concluded 10 years later, but referenda held in the country in 1972 and 1994 failed to return a sufficient majority in favour of entry, although the country has remained within the EEA. Switzerland’s desire for neutrality (and financial secrecy) has outweighed any perceived advantages of membership. The country rejected membership of the European Economic Area (EEA) and thus the possibility of EU entry in 1995. Iceland has also shown no interest in membership. Greenland (Kalaallit Nunaat) is one ‘country’ to have actually withdrawn from the European Union, in 1985, having become a self-governing overseas administrative division of Denmark in 19793 (Abbott, 2016). By contrast, Turkey first applied for membership in 1987.

UK public debate on the nature and significance of such experiences as possible pathways outside the EU tended to be limited and superficial (see Table 2.2).

Some of the most significant outcomes of the combination of deepening and widening processes have related to the encouragement of the free mobility of people within the EU. This has been reflected not only in tourism and leisure travel, but in education and employment mobility. The migration of relatively cheap labour from east to west has represented both a concern and a significant boost for some national economies, not least that of the UK, especially in terms of providing a flexible workforce for many elements of the tourism and hospitality sectors (Chapter 6) and seasonal labour in horticulture where local supply has appeared insufficient.

Figure 1.1 The European Union: Stages of ‘widening’

As a concomitant to the removal of internal barriers to the flow of people, goods and ideas within the EU, there has been a requirement to tighten the external borders of the Union, a dimension at the heart of the apparent mutual incomprehension between the EU and the UK government concerning the UK-Republic of Ireland border (Chapter 9). Crossing the external borders of the EU to enter one member state in effect provides legal entry to all EU member states, internal differentiation between Schengen zone and non-Schengen members notwithstanding. With tourism as an essentially national competence, EU mobility strategies have nonetheless emphasised the range of policy areas that impact upon tourism, including those for SME growth, supply chains, welfare and environmental sustainability (see Chapter 3).

Within this context, until relatively recently tourism had ‘… registered great difficulties in obtaining its legal and political recognition’ within the EEC/EC/EU frame (Rita, 2000: 434–435). Rita attributed this situation to three apparently interrelated factors:

(i) a misunderstanding of tourism’s breadth coupled to and resulting from an inadequate evaluation of its economic, social and cultural significance;

(ii) a political under-assessment of tourism activity and its potential for Europe’s future; and

(iii) obstacles within the Commission, successive presidencies and certain member states. (Rita, 2000: 435)

Certainly the EU has been significant in providing advisory frameworks and guidelines for the tourism sector within Europe, and perhaps most notably in the area of consumer protection. One of the better known examples of this being the 1993 Directive on Package Travel (updated 2013) which made it illegal for travel organisers and/or retailers to fail to provide their clients with necessary information on health needs.

While the European Commission has recognised tourism as one of the most significant activities in the EU in terms of economic benefits (employment, income and wealth creation in local communities), and social benefits (as a framework for the stewardship of distinctive cultures and environments), tourism has been denied a guiding policy that could be developed into a European model (Anastasiadou, 2011; Halkier, 2010; Manente et al., 2013).

As Estol and Font (2016) highlighted, tourism has remained a tool or ‘common action’ – in practice a means to an end – for such grander policy objectives as convergence to the Single Market (Anastasiadou, 2008b; Aykin, 2012), equity and social cohesion, sustainable development (Anastasiad...

Table of contents

- Frontcover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures, Tables, Boxes

- Abbreviations

- Preface

- Author Details

- Section A Context

- 1 The UK and ‘Europe’

- 2 Imbroglio

- 3 Tourism and the EU: Retrospect and Prospect

- 4 Theorising Brexit and Tourism

- Section B Tourism Impacts

- 5 Impact Assessments and Perceptions

- 6 Supply-side Issues

- 7 Demand-side Issues

- Section C Implications

- 8 Environmental Implications

- 9 Inconvenient Cross-border Mobilities I: Ireland

- 10 Inconvenient Cross-border Mobilities II: Expatriate Citizens’ Free Movement Rights

- 11 Inconvenient Cross-border Mobilities III: Gibraltar

- Section D Global Britain?

- 12 Commonwealth

- 13 Pursuing the Chinese Market: Symbol of a ‘Global Britain’?

- 14 Conclusion: The UK as a ‘Great’ Destination?

- References