Part 1

The Contentsization of Literary Worlds

1The Contents Tourism of Jane Austen’s American Fans

Philip Seaton

The UK is one of the leading nations for literary tourism. Many famous writers from William Shakespeare to J.K. Rowling have penned works that have induced major tourism phenomena. However, in the digital age, the written word frequently reaches consumers simultaneously via multiple other formats – such as screen adaptations, graphic novels and theatre – and fans themselves are engaged as prosumers – consumers who also produce spin-off works, events, fan websites and travel books/blogs. When such multi-use occurs, an author (Jane Austen), character (Harry Potter) or franchise (Game of Thrones) can become a byword for a broader ‘narrative world’. When this narrative world induces tourism, it becomes more appropriate to talk of a ‘tourism imaginary’ (Chronis, 2012), ‘places of the imagination’ (Reijnders, 2011) or contents tourism (Beeton et al., 2013; Seaton et al., 2017), rather than ‘literary tourism’.

While accepting that examples of discrete media format tourism do exist – Lord of the Rings tourism in New Zealand is film-induced tourism, and travel to Thomas Hardy sites by someone who has only ever read the books is literary tourism – such examples are getting ever harder to identify in our increasingly media-saturated world. In the Introduction to this book, Takayoshi Yamamura identified the concept of ‘contentsization’ as a ‘continual process of the development and expansion of the “narrative world” through both mediatized adaptation and tourism practice’. This chapter argues that the current popularity of Jane Austen, one of English literature’s most revered authors, is more than a phenomenon of ‘convergence’ (Jenkins, 2006) or ‘transtextual worlds’ (Hills, 2015), whereby the original novels have triggered multiple adaptations in various formats by both professional media producers and amateur fans. Tourism and the fan performances at tourist events (such dressing up in period costumes at the Jane Austen Festival in Bath) play a central role in the process of contents expansion and the ongoing development of ‘Austen’s world’. In this sense, the current Austen boom is an archetypal example of contentsization. So, while Austen-related tourism has typically been treated as literary tourism (for example Crang, 2003; Herbert, 2001; Wells, 2011: Chapter 4) – and I would concur that in its early stages it was primarily ‘literary tourism’ – there has been a paradigmatic shift in the nature of Austen-related tourism towards contents tourism, with the year 1995 as the key moment in that transition.

The chapter starts with an historical overview of this evolution in ‘Jane’s Fame’ (Harman, 2009) and its relationship to Austen-related tourism. Then, with a focus on Austen’s American fans, the motivations for Austen-related contents tourism are examined, and in particular the ways in which Austen-related tourism fits into the broader imaginations and itineraries of American visitors to Britain.

Visiting Jane’s World: From Literary Tourism to Contents Tourism

When Jane Austen died in 1817, she was relatively unknown. She had some ardent admirers in the mid-19th century, but ‘Janeitism’ did not emerge until the 1880s, after J.E. Austen-Leigh’s biography A Memoir of Jane Austen and the first collected edition of her works were published in 1870 and 1882, respectively (Johnson, 2011: 232). Her works were the subject of debate within literary circles in the early 20th century, but the popularized ‘Austenmania’ (Todd, 2015: Chapter 9) or ‘Jane AustenTM’ (Harman, 2009: Chapter 7) of today largely dates from the 1990s. The cause of this modern wave of popularization is screen adaptations. The first Austen film was the 1940 Pride and Prejudice starring Lawrence Olivier and Greer Garson. Thereafter, there were radio plays and television serials that were theatrical in nature and adhered closely to Austen’s original dialogue. However, in 1995, there were three major screen adaptations: the BBC’s Pride and Prejudice, Columbia’s Sense and Sensibility and a BBC telefilm of Persuasion (Sutherland, 2011: 218–219). Then, with two adaptations of Emma appearing in 1996, four of Austen’s six completed novels had been adapted for large and small screen and released within two years (Higson, 2011: 132–133). In particular, Pride and Prejudice – with its iconic scene of Elizabeth Bennet encountering a wet-shirted Darcy (Colin Firth) after a swim in the lake in the grounds of Pemberley – ignited Austenmania. The thesis of this chapter is that, mirroring the development of Austenmania as a whole, tourism relating to Austen underwent a fundamental transformation in 1995. Up until 1995, Austen-related travel was primarily literary tourism. However, after 1995, travel to a tourism imaginary we may call ‘Austen’s world’ has been inspired by screen adaptations and derivative works as well as the novels in a phenomenon better termed contents tourism.

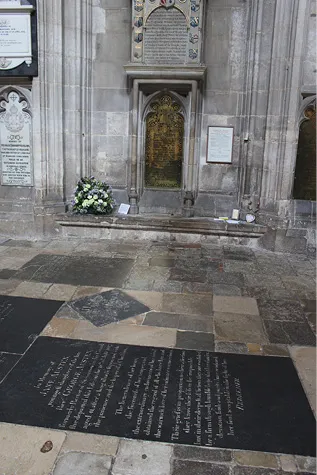

Austen-related tourism dates back to the 19th century. Literary tourism was a recognizable phenomenon during Austen’s lifetime and by a few decades after her death, Austen’s fans were already travelling to places connected to her life or depicted in her novels. ‘Appreciative readers in the 1850s began to search for their favourite author’s burial place in Winchester Cathedral, “the shrine of Jane Austen”, one woman called it’, writes Hazel Jones, who also describes a journey to sites where Austen lived undertaken by Constance and Ellen Hill in 1901 (Jones, 2014: 157). Readers also engaged in location hunting, for example, Alfred Lord Tennyson made a trip in 1867 to find the location in Lyme Regis made famous by a scene in Persuasion, in which Louisa Musgrove fell down some steps (Jones, 2014: 159). These trips were all taken long before any adaptations or the commercial touristification of Austen-related sites.

The touristification of Jane Austen began in 1949 with the opening of the Jane Austen’s House Museum in Chawton. Austen lived in this house from 1809 to just before her death in 1817, and it was where she wrote or revised for publication her major works. This is a key site of pilgrimage for Austen fans, along with her birthplace in Steventon (Figure 1.4) and her grave in Winchester Cathedral (Figure 1.1). The museum operates as a site of artefact preservation and scholarship as much as a tourist site, along with other sites holding collections of Austen manuscripts, letters and memorabilia, such as the Bodleian Library in Oxford and the Morgan Library in New York. Research by David Herbert in 1993 and 1994 indicated a strong element of literary tourism at Chawton: in a sample of 223 respondents, 60% of visitors interviewed had read three or more of Austen’s novels (Herbert, 2001: 322).

Figure 1.1 Jane Austen’s grave in Winchester Cathedral (September 2017). In the alcove at the back are messages to Austen left by fans. Author’s photo

More commercialized touristification aimed at the casual rather than scholarly consumer emerged during the mid-1990s. The trigger was the BBC’s adaptation of Pride and Prejudice. Visitor numbers at Jane Austen’s House Museum had stabilized at about 20,000 people per year by the early 1990s, but Pride and Prejudice ‘changed everything’ (Smith, 2016). Around 55,000 people visited in 1995, and the museum was so crowded that time tickets had to be introduced. After the boom, visitor numbers returned to 37,000–40,000 per year, but this was still almost double the pre-drama levels. The various 200th anniversaries between 2009 and 2017 (Austen moving to Chawton 1809, publication of Pride and Prejudice 1813, death in 1817) ensured that visitor numbers moved back towards 50,000 a year.

Jane Austen’s House Museum was not the only place seeing increases in visitor numbers. Lyme Park, a stately home in Cheshire, had no connection to Austen prior to the BBC’s adaptation, but its visitor numbers soared after the series. The external Pemberley scenes were shot there and Lyme Park became an important destination for Austen fans. Visitor numbers tripled in the year after the broadcast of the series from 32,852 pre-transmission to 91,437 post-transmission (Parry, 2008: 116). Lyme Park...