eBook - ePub

Dangerous Love

Transforming Fear and Conflict at Home, at Work, and in the World

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

'ÄúChad Ford reminds us that humanity lies within all of us, and although conflict is everywhere in today's world, we have the tools we need to overcome obstacles and to thrive. This is a fantastic, timely book that I highly recommend."

-Steve Kerr, Head Coach, Golden State Warriors

Knowing how to transform conflict is critical in both our personal and professional lives. Yet, by and large, we are terrible at it. The reason, says longtime mediator Chad Ford, is fear. When conflict comes, our instincts are to run or fight.

To transform conflict, Ford says we need to turn toward the people we are in conflict with, put down our physical and emotional weapons, and really love them with the kind of love that leads us to treat others as fellow human beings, not as objects in our way. We have to open ourselves up with no guarantee that anyone on the other side will do the same. While this can feel even more dangerous than conflict itself, it allows us to see the humanity of others so clearly that their needs and desires matter to us as much as our own.

Ford shows dangerous love in action through examples ranging from his work in the Middle East to a deeply moving story about reconciling with his father. He explains why we disconnect from people at the very time we need to be most connected and the predictable patterns of justification and escalation that ensue. Most importantly, he gives us a path to practice dangerous love in the conflicts that matter most to us.

-Steve Kerr, Head Coach, Golden State Warriors

Knowing how to transform conflict is critical in both our personal and professional lives. Yet, by and large, we are terrible at it. The reason, says longtime mediator Chad Ford, is fear. When conflict comes, our instincts are to run or fight.

To transform conflict, Ford says we need to turn toward the people we are in conflict with, put down our physical and emotional weapons, and really love them with the kind of love that leads us to treat others as fellow human beings, not as objects in our way. We have to open ourselves up with no guarantee that anyone on the other side will do the same. While this can feel even more dangerous than conflict itself, it allows us to see the humanity of others so clearly that their needs and desires matter to us as much as our own.

Ford shows dangerous love in action through examples ranging from his work in the Middle East to a deeply moving story about reconciling with his father. He explains why we disconnect from people at the very time we need to be most connected and the predictable patterns of justification and escalation that ensue. Most importantly, he gives us a path to practice dangerous love in the conflicts that matter most to us.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dangerous Love by Chad Ford in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Berrett-Koehler PublishersYear

2020eBook ISBN

9781523089796Subtopic

Conflict ResolutionCHAPTER 1

DANGEROUS LOVE IN THE DESERT

The glue that holds all of our relationships together is the mutual recognition of the desire to be seen, heard, listened to, and treated fairly: to be recognized, understood, and to feel safe in the world. When out identity is accepted and we feel included, we are granted a sense of freedom and independence and a life filled with hope and possibility.

—DONNA HICKS

“But what if he’s a bad man?” Miriam, a Middle Eastern woman in her early twenties, asked me the second day into our conflict transformation training. “I understand all of this ‘dangerous love’ talk. But what if the person that is single-handedly keeping our organization from being successful is evil? Are we just supposed to sit back and let him win?”

Miriam and a small group of young women had recently started a small nonprofit that was struggling to gain traction in the community. Their stated goal was to get young Muslim women interested in sports as a way to create identity and self-worth. But they kept running into a huge obstacle. The nonprofit didn’t have enough money to build their own sports facilities. The owner of the only gym in the community, Mahmoud, refused to allow women to play there.

Miriam had gone to Mahmoud several times asking for an exception. Each time she was rebuffed. Without the gym, the group had no permanent place to operate from. People in the community were struggling to take them seriously.

As Miriam spoke about Mahmoud, her frustration was evident. She had tried to be nice to him and to understand what his motivations were. She had offered to pay him in exchange for the use of the gym. When her offer failed, she tried to picket his gym in protest. No matter what she did, he kept refusing, and the more he refused, the more Miriam became convinced that he was their biggest problem—another sexist, old, stuck-in-his-traditional-ways male refusing women their equal rights.

Miriam and the others in the room were wrestling with the basic ideas taught by the Arbinger Institute. At the heart of Arbinger’s work is the idea that we can see people in one of two ways—as people or as objects.1 See people as objects and we have an inward mindset. See people as people and we have an outward mindset.2

However, seeing people as people is extremely challenging when we are in the midst of a destructive conflict. The women were finding it hard to apply the concepts of dangerous love to themselves.

How do you practice dangerous love when the person you are in conflict with embodies the very evil you are trying to fight? That doesn’t feel dangerous. It feels like suicide.

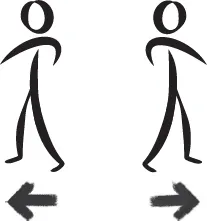

Imagine two people standing back-to-back, elbowing each other, as illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1. The conflict figure.

They can feel each other, but they can’t see each other. Each person blames the other person for not seeing him or her.

The more the two get elbowed, the more convinced they are that they actually see the very people they aren’t seeing. They magically know their thoughts, motivations, and character—and the verdict isn’t good.

Both people wait, hopelessly, for the other person to turn and see them. They both decide that if the other person turns, then they will turn too. Unfortunately, they also don’t believe the other person will ever actually turn. The longer they wait in vain for the other person to turn, the more frustration, helplessness, and fear they feel.

In these sorts of conflicts, people get stuck in a rut of

- Self-absorption: seeing only their own pain

- Weakness: feeling helpless to do anything about it

Miriam is experiencing both. She has a nonprofit to run. She needs help. The only person in town with the facilities to help her won’t help. No matter what she does, he keeps saying no. All she can think about is how Mahmoud is making her life difficult.

When we get stuck in conflict, we have a hard time seeing other people as people. Our mindset turns inward.3 We start seeing the situation only through the lens of how others affect us. Once that happens, we start exacerbating the very conflict we say we want to end.4 When we try all the ideas that we think should work from that inward, self-absorbed, weak position and they fail, conflict feels intractable.

Intractable is scary. In the face of fear, whether that be toward a teenager, coworker, or community member, we rarely are our best selves.

We run if we can. If we can’t, we retaliate. We fight. The situation gets worse. We say we want the conflict to end but only on our terms. And our terms typically require the person we are in conflict with to turn and see us as people first. That will not happen with Mahmoud as long as Miriam is picketing his gym.

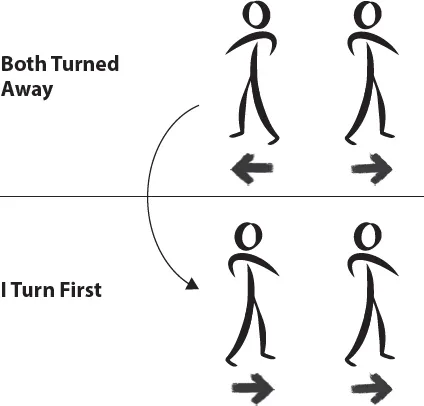

The other option is obvious. It’s also dangerous. We find the strength to love—to be the first to turn and see the people we are in conflict with as people. This act of turning toward others—first, and without expectation or demand that they turn as well—is what Arbinger calls “the most important move” (figure 2).5

Figure 2. The most important move.

Ask people why they don’t turn first, and safety and vulnerability always come up. Being the first person to turn feels dangerous. “They started it! What if they don’t turn back? What if they take advantage of me or take my turning as a sign of weakness?”

That’s where Miriam and Mahmoud were stuck. I suspected there was more going on with Mahmoud than Miriam believed, but each time I pressed her, she resisted.

“You don’t know him,” she said. “No one, not even the men in the village, likes him. He will never change.”

I asked Miriam what she really wanted.

“The gym!” she replied.

I asked her why.

“Because our organization can’t work without it!”

Then I asked her why the program was so important to her.

She talked about the struggles she and other women and girls in the village faced. She talked about how she felt her culture and the people in her village saw her as less important and her dreams less real than those of men.

After several more “why” questions, she got there: “I don’t ever want other young girls to feel the way I felt. It’s too late for me. But it isn’t too late for them.”

Then I asked her whether the path that she was taking to get to her “why” adhered to the same values of seeing everyone as important and everyone’s dreams as equally real.

She said she didn’t know.

I asked Miriam a number of questions about Mahmoud, and it turned out she knew very little about his background—why he owned the gym or even why he was refusing to let the group use it. That was the first clue that maybe she wasn’t seeing Mahmoud the same way she wanted him to see her.

However, one interesting tidbit did emerge. Since Mahmoud had the only gym in the village, everyone was constantly asking him to use it for free. There wasn’t much money in the village, and most of the villagers could not afford to pay the gym fees.

I asked Miriam to imagine how it must feel to be constantly approached by people asking for help—even when giving that help compromised Mahmoud’s ability to run a successful business.

Miriam paused and huddled with the others in her nonprofit. They hadn’t thought about the problem that way before. They were the ones with problems, not Mahmoud. Once they saw a potential problem that Mahmoud might be facing, the question they began to ponder was this—“What could we do to be helpful to Mahmoud?” By the end of the weekend, they had a plan.

Miriam said that when they got back home, they were going to offer to clean the gym for Mahmoud every night after it closed. They would do it for free. Their hope was that he would see that the girls were both kind and serious and would eventually grant them access to the gym.

Miriam and her colleagues left the workshop encouraged that there might be a way out of the conflict that they hadn’t thought of and promised to send updates.

A few weeks later I heard from Miriam.

“Good news,” she wrote in her email. “Mahmoud has allowed us to clean the gym. We have been working for several weeks and he seems happy. Each night he brings us tea and thanks us. We want to ask him if we can use the gym now. What do you think?”

Miriam already thought she’d done enough to begin asking Mahmoud to change.

I wrote back, “That is great. Are you seeing him as a person yet?”

She replied, “I don’t know.”

Gandhi taught that the means are the ends in the making.6 If the group cleaned the gym to truly help Mahmoud, they couldn’t fail—even if he wouldn’t let them use the gym. If they did it to try to persuade or manipulate him to let them use the gym, it would likely be a disaster. How Miriam saw Mahmoud would ultimately decide their relationship, not what she did.

Miriam thought the way out of the conflict was by helping him see her as a person. Why? Because helping or forcing someone to see you as a person feels much less dangerous than seeing someone as a person regardless of how he or she sees you.

While the move feels authentic, it is still, primarily about me. And if it fails, if she had asked to use the gym and Mahmoud had said no, do you think she would keep seeing him as a person?

Dangerous love can’t be contingent on the people we are in conflict with loving us back. If we have to wait for an assurance that others will reciprocate, we could be waiting forever.

I wrote to Miriam, “Are you cleaning the gym because you care about Mahmoud and want to be helpful to him? Or are you doing it because you want him to change? Only you really know whether you are seeing him as a person or not.” The answers to those questions would help Miriam decide whether she was practicing dangerous love yet.

“I think we need to wait,” was her short retort.

A few weeks later, Miriam wrote again: “We are still cleaning the gym. Mahmoud keeps spending more and more time each night talking to us. We have even been invited to his home for dinner. Can we ask him now? Maybe at dinner?”

“Are you cleaning his gym for the right reasons yet?” I replied. “What have you learned about Mahmoud? Do you understand why Mahmoud is turning you away? Do you know what his goals and challenges are? Until you understand what he’s trying to achieve, you won’t know whether it’s even right to ask.”

Several days later, another email came through.

“You are not going to believe what happened at dinner. We met Mahmoud’s wife. She was especially warm to us. She kept telling us how surprised and delighted she was that her husband had invited us over.”

For privacy’s sake, I can’t get into the details of what...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction: What Is Dangerous Love?

- Chapter 1. Dangerous Love in the Desert

- Chapter 2. Practicing Dangerous Love

- Chapter 3. Seeing Conflict as Smog

- Chapter 4. Overcoming Our Fear of Conflict

- Chapter 5. How a Smog Thinker Fights Conflict

- Chapter 6. How a Cocoon Thinker Transforms Conflict

- Chapter 7. The Chasm of Separation and Self-Deception

- Chapter 8. Bridging the Gap between Fear and Love

- Chapter 9. Mistakes Were Made

- Chapter 10. But Not by Me

- Chapter 11. Escalating Conflict

- Chapter 12. What War Is Good For

- Chapter 13. Waiting for Them to Turn

- Chapter 14. Turning First

- Chapter 15. The Kumbaya Fallacy

- Chapter 16. Inviting Them to Turn

- Chapter 17. Truth, Mercy, and Justice

- Chapter 18. Keeping the Peace

- Chapter 19. The Long-Short Way

- Chapter 20. Small and Simple Things

- Chapter 21. Troubleshooting Dangerous Love

- Chapter 22. Choosing Love over Fear

- Notes

- List of Stories

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- Additional Resources

- About the Author