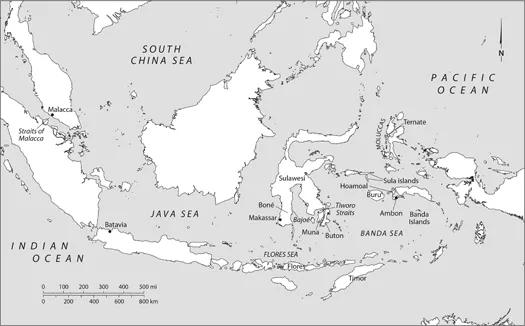

Chapter two looks at the northern east-west route across the archipelago, and at Makassar’s hinterseas, delving into the historical background of seventeenth century maritime networks. While subsequent chapters consider the significance of enduring dynamics in the archipelagic world, in this book I primarily approach maritime history via the strands of the networks that people made. The point is not just to see the networks’ connected elements, but also to understand what those connections were made of and how they worked. Intersecting maritime networks formed nodes, and tugging gently at them shows how networks fit together in archipelagic space, which was not two-dimensional. At once ecologically and historically made, it was also a social and political space. What can be discovered about this archipelagic past depends on the use of some mixed methodology, and, as with all history, on the point of view of the sources used and how the historian handles them. The key here is not to go to sea from the land, for if one does that one will always return to it. Instead one must launch, as people did, from the littoral itself.

CAPTURE, CONNECTION, AND FOLLOWINGS

When Lawi was taken in 1954 from her coastal village in the Straits of Tiworo, Indonesia was barely a nation. Although Lawi, too, was quite young, she had her eye on a man named Umar. She had been promised to him, and while no formal gift exchange—no deal-sealing—had yet taken place between their families, her relatives had already begun to gather the quantities of rice that would be needed for a wedding. Then the rebels came for her.1 Lawi was Sama, an ethnic group often referred to as “sea people,” usually called “Bajo” by others. She was “captured” (taken against her will) in order to be married to a regiment commander in the Darul Islam rebellion, which was then spreading throughout most of south and southeast Sulawesi.

Darul Islam, or “DI-TII,” the common acronym that includes its armed wing, the Indonesian Islamic Army (Tentara Islam Indonesia), was just one of many groups that struggled over the new nation’s future during the early post-independence period. The Bugis dominated the Sulawesi branch of DI-TII, which had two other main branches and smaller offshoots elsewhere in the country. Jufri Tambora, the regiment commander to whom Lawi was wed, was ethnically Bugis. Lawi’s capture and marriage to Jufri came as an unwelcome development in the predominantly Sama Tiworo Straits. After she was taken, two rebel men dared to visit her village once again, apparently to persuade relatives to join her at their base in the hills. They compounded the offense of her capture by attempting to extort money from her father, who had been away at the time she was taken, on a trading trip to Lombok with his youngest son, Buraéra. When the two rebels returned, recognition of them by Lawi’s relatives led to retaliation against them.

While Lawi’s kin were angered and distressed about her capture, it also put them in the difficult position of having to suppress knowledge of her whereabouts. When her captors permitted her a visit to her natal village, people even felt compelled to turn her away because they could not afford to have it appear, in the eyes of the TNI (Tentara Nasional Indonesia, Indonesian National Army), that they were siding with the rebels. Convincing the TNI of their allegiance to the nation was a matter of collective survival for Lawi’s neighbors and relatives, and among wider networks of Sama kin. The ramifications of her capture, therefore, played out both at the level of intergroup relations and in the wider struggle of post-colonial politics. At the same time, intergroup relations and their part in the broader maelstrom of the early post-colonial period unfolded between littorals. That is, they took place between land and sea, directly involving the maritime-oriented Sama people of Tiworo and the surrounding region.

Lawi’s spouse, Jufri, knew a great deal about how maritime trade worked. During the Second World War, before he became a Regiment Commander, he had been an informant for the occupying Japanese, filling them in on who was spying for the Dutch, the previous colonial overlords. The trust he gained as an informant earned him a position as harbormaster (syahbandar) for Binsen Ongkōkai, the Japanese Tramp Shipping Transport Company, in the town of Kolaka, on the Gulf of Boné’s east coast. He managed the paperwork for “tramp” freighters, cargo boats that had no fixed schedule. The paperwork included permits to sail, as well as bills of lading. Common in the world of shipping even today, bills of lading serve both as a receipt for goods delivered to carriers and as a description of the goods, as well as evidence of title to them. They show that a shipper is not carrying contraband. Jufri’s position as the enforcer of rules about shipping papers taught him many things. He not only learned who carried what cargo under which terms, but also came to understand that notions of legitimate trade were flexible under wartime interpretations of legality. One thing Jufri’s experience drove home was the importance of having the right papers, which seemed to confer legitimacy not only to shippers, but also to the governing body that recognized their documents. Later, during the Darul Islam years, this lesson came into play when his sister, Sitti Hami, ran a smuggling ring for DI-TII, issuing papers under its authority, even as smugglers also carried counterfeit passes in case they were stopped by the other side in the conflict. Jufri, in his administrative role over mariners at Kolaka’s harbor during the Japanese occupation, kept an eye out for paperwork that came up short. If and when it did, the potential for lucrative gain, or for brokering knowledge about smuggling opportunities, would have been obvious to him. In effect, the job as harbormaster under the Japanese gave him a deep understanding of how smuggling worked in practice. All he lacked were the nautical skills, the distant clandestine connections, and the savoir faire to pull it off. For these he would need real mariners with experience.2

He obtained the allegiance of his most trusted smuggler during the Darul Islam rebellion through his marital connection with the Sama. While most of Lawi’s relatives kept quiet about her link with the rebels, her brother, Buraéra, who had been captured by the rebels on a separate occasion, eventually managed to take advantage of his new kin connection as the regiment commander’s brother-in-law. In a bid to extricate himself from a combat position under Jufri’s nephew, Buraéra offered his services as a smuggler for the rebellion. A Sama man with a special set of nautical skills, he drew on the experience and knowledge he had gained as a young mariner on trading ventures across the archipelago with his father. Jufri derived benefits from Buraéra’s skills, knowledge, and networks. Buraéra, in turn, eventually became the regiment commander’s trusted adjutant.3

While discussing the clandestine maritime trade of the 1950s with me, Jufri, then in his dotage, raised the topic of his personal relation to Sama people, namely, his marriage to Lawi. He said he had married a Sama woman from the raja class, in other words, a woman from a high status lineage, and he noted that it had caused some fear. That he drew a link between clandestine trade or smuggling on the one hand, and his marriage to Lawi on the other, indicated that in his mind the two were related. His comment about fear in the same breath made me think that the manner in which their kinship connection was brought about also mattered. Fear of him and for Lawi, he implied, helped motivate the compliance of her Sama kin, even though there had been some retaliation. It was via kinship and fear that Jufri endeavored to create, and to some degree succeeded in creating, a path to gain followers with specialized nautical skills, from whose networks he could benefit. Without this kin connection, Jufri may have wound up commandeering their boats anyway, as he did on occasion, simply for a show of strength. However, had it not been for Jufri’s union with Lawi, it is unlikely that her brother Buraéra would have become a smuggler for the rebellion. Their marriage provided Buraéra a way to improve his circumstances, and concern for his sister’s well-being kept him from absconding. Jufri cemented Buraéra’s loyalty with the position of adjutant, and, to hear Buraéra tell it, with fear as well.4

These events during the 1950s provide rich material for exploring the politics that took shape around the need for seafaring skills, nautical manpower, and specialized social knowledge in the maritime world. When set alongside this book’s examination of the seventeenth-century archipelago, the 1950s material suggests the durability of a politics in which forging social connections with maritime people conferred nautical advantages. In this archipelagic environment, cultivating such connections opened up, or reinforced, access to the intangible yet invaluable assets of maritime people’s skills and networks. Since maritime people usually inhabited the littoral, often in places distant from land-based powers and in ecological zones that made it hard for others to reach them, they were able to maintain a measure of maneuverability independent of established polities on land. If powers based primarily on land wished to benefit from maritime skills and networks, it behooved them to form compelling links with maritime people.

For Lawi and Buraéra, whose stories I return to in chapter five, capture, kinship, fear, and conferral of rank were political tools that made and maintained their connections with Bugis leaders during the Darul Islam rebellion. Yet these methods of gaining nautical advantage were not a new part of intergroup dynamics in the archipelagic world. During the seventeenth century, as this work shows, the bestowal of rank, both by the Gowa court at Makassar, and subsequently by the Bugis realm of Boné, also cemented the loyalty of maritime-oriented people who possessed both nautical and martial skills. Rank was conferred on people viewed as having, or having the potential, to garner followings. Likewise, during the seventeenth century, capture had an impact on followings that was not simply about the acquisition of dependent labor. For instance, the capture of women led to new, subordinate kin connections, yet it also sundered existing ties of foes, thereby weakening the longstanding friendships and relations they maintained with maritime allies and their networks.

Tiworo’s ties with Makassar endured just this sort of blow. Closely allied with Makassar, the most powerful port polity in the central and eastern archipelago, Tiworo’s people suffered the capture of three hundred women and children, which sealed its military defeat in 1655. Although this large scale capture did not prevent Tiworo’s rejuvenation over the next decade, the redistribution of Tiworo’s women and children to Makassar’s enemies not only wrested them from where they lived, but also removed them from Makassar’s political orbit and made them, however reluctantly, into “followers” of its foes. Such capture and redistribution of victims among foes was a tool of politics and a means of domination.

Whether used to forge or to rupture connections, the capture of women, in particular, was never simply neutral. Its salience is evident in how Sama capture narratives got taken up and adapted to new contexts, in literary-historical texts from southern Sulawesi (Celebes) that euphemized capture and effectively erased it. To unders...