![]()

1

The I/eye of capital: Classical theoretical perspectives on the spectral economies of late capitalism1

Thomas M. Kemple

Social theory today is itself an instance and integral part of contemporary capitalism. As advertising executives learn to use semiotics and industry teaches academia lessons about cultural studies, even the most abstract forms of thought become subject to capitalization and capital finds new ways of absorbing critical modes of thinking. In a recent book, Knowing Capitalism, Nigel Thrift makes this point by offering what he calls “a history and geography of the near present” which avoids simply summarizing academic critiques or theoretical analyses of the current state of capitalism, since he finds them to be impotent or unconvincing in view of the system’s ability to exploit and co-opt them. Instead, he shows how businesses—including universities and research institutes around the globe—are in the business of selling ideas, marketing innovative knowledges, and promoting novel ways of thinking: “Management theory relies, more than other forms of virtual knowledge, on a conglomeration of performed and book knowledge, and the two are not exclusive but form a part of a chain of production and communication” (Thrift 2005, 91). Managerial ideas and lucrative thought-styles increasingly originate and circulate beyond academic institutions, in the course of which they are communicated not just through formal and traditional media, such as books, tapes, videos, and magazines, but also in informal and less conventional settings, such as email discussion groups, online forums, workshops, retreats, television shows, and speaking tours. As new ways of knowing and doing capitalism emerge through triangulated exchanges between business schools, management consultants, and entrepreneurial gurus, aspiring traders in ideas, information, and other intellectual goods from within and outside the university draw their inspiration from anti-capitalist critics, oppositional social movements, and enterprising academics (Gibson-Graham 2006). In the process, subcultural and intellectual counter-currents become integrated into the cultural and cognitive circuits of capital, and the ‘portfolios’ of individuals and organizations increasingly include not just material wealth and financial capital but also “stocks” of commercial acumen which incorporate the speculative competence of reflexive institutional and personal knowledge.2

Arguably, the classic social theorists of Western capitalism writing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries might be said to have anticipated or even welcomed these developments. They found ways of accommodating themselves to rapidly developing changes in the capitalist world system while also trying to insulate themselves from its most pernicious and damaging effects. When Karl Marx was living in poverty with his wife, daughters, and mistress–maidservant in London’s Soho while studying the latest government-issued factory reports and economic texts for his magnum opus Capital, he was also drawing a modest income from Engels’ family-owned textile industries in Manchester, from local pawn shops, and from his occasional editorials for the New York Daily Tribune. A generation later, Georg Simmel struggled to make ends meet in Berlin from his low salary as an adjunct university professor, for the most part by lecturing and writing on a wide variety of cultural and social phenomena emerging out of the rise of the money-economy, the subject of his masterpiece The Philosophy of Money. In the same years, Emile Durkheim fought for educational reforms from his academic chair at the Sorbonne in Paris, reforms which he saw as necessary for morally and institutionally regulating the anomic effects of the industrial crisis which he diagnosed in The Division of Labour in Society. Finally, around the same time, Max Weber was studying the historical origins of the entrepreneurial ethos in his Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, making recommendations about German national economic policy in rural areas and in urban stock exchanges, while also drawing on his wife’s inheritance from her family’s weaving manufactories. Far from merely formulating canonical concepts for analyzing the capitalist system from outside it, as one might surmise from Anthony Giddens’ 1971 textbook Capitalism and Modern Social Theory (for years a staple of courses in classical social theory), these early thinkers were deeply implicated in the mechanisms and movements of capitalism. Each acknowledged that social theories of the contemporary financial and industrial order cannot simply project an external view of its form; they must also take up a perspective from within its very substance—conceived as “exchange-value” in the case of Marx, as “social interaction” for Simmel, as “symbolic institution” in Durkheim’s work, and as “rational action” for Weber.

Rather than merely reviewing these founding theories of early capitalism, I want to consider them as starting points for critically rethinking certain features of what I shall call the spectral economies of late capitalism, that is, the tendency we are experiencing today toward the financialization, electrification, and virtualization of capital in all its forms. In other words, the basic unit of contemporary capitalism seems to have morphed from the circulation of the commodity, defined by its exchange-value (as expressed through price fluctuations, for example), to the communication of cultural style, perceived in terms of the differentiation of sign-values (as in can be seen in the competition between brands). Likewise, economic activity now turns as much on the fixed assets and guaranteed securities of privately owned businesses as on high-risk and mobile investments made by institutional shareholders. The very real “spillovers” of economic transactions (or “externalities” in neoliberal jargon) therefore do not just entail environmental damage, poor health, and income inequality. They also include the virtual side effects of financial crises and speculative meltdowns of markets in stocks, bonds, loans, and funds (Lash 2010, 116–25). In what follows, I argue that the acceleration, extension, and intensification of capitalism that we see today does not require us to throw out the baby of classical social theory (Theory 1.0) with the bathwater of corporate thinking (Theory 2.0). Canonical concepts such as commodity-fetishism, rationalization, discipline, and (de)individualization, for example, still afford us some critical perspective on the potential within contemporary capitalism for political transformation and civic regeneration (O’Neill 2004).

Exploiting distraction: Beyond Marx and Simmel

In Marx’s draft for a chapter he planned to write on “The Results of the Immediate Process of Production,” which he ultimately abandoned but which is often included as an appendix in posthumously published editions of the first volume of Capital (Capital I), he elaborates on the key theoretical distinction around which most of the main text is organized: between “absolute surplus value” on the one hand—the value added to capital by the extension of the working day or the expansion of markets and manufactories—and “relative surplus value” on the other, which accrues through the acceleration of the work process or by increasing output through technological innovations. In the draft notes, Marx generalizes this argument by contrasting what he calls “the formal subsumption of labour under capital,” in which the activity and outcome of the work process remains unaltered as it is appropriated, circulated, and consumed capitalistically (for instance, when traditional handicrafts are sold on the world market), with “the real subsumption of labour under capital,” in which the production process itself is fundamentally transformed and reconstituted (such as when subsistence agricultural work is replaced by capitalist industrial labor; see Marx 1977, 1019–38). The historical shift that Marx was already able to identify as a tendency inherent in the dynamics of early capitalism—from absolute to relative surplus value, and from formal to real subsumption—is accelerated and intensified in late capitalism. For example, the proliferation of new design technologies and high-tech marketing campaigns aim at enhancing (relative) surplus value, while expanded outsourcing and lending practices, mergers and acquisitions, tend to foster (real) subsumption. Generally speaking, capital does not just subsume the laboring body by appropriating its intellectual and material capacities (the possessive individual), but also the living body (the possessed individual) whose needs, desires, and thoughts are seized upon and developed by the process of capital itself (Kroker 1992). As Marx expresses this point in the Grundrisse, the prosthetic and parasitical potential of capital to absorb the laboring body enhances its human potential while forging new technical and social dependencies, a process which entails “the production of capital fixe [fixed capital], this capital fixe being man himself” (Kemple 1995, 24–7; Marx 1973, 712). Today this tendency has been intensified insofar as life itself—in its social, human, intellectual, and biological dimensions—is technologically reconstituted and marketed not simply as a fixed and firm product of capital but also as a circulating and mobile medium of its flux and flow.

In general terms, capital does not increase solely by enhancing instrumental efficiency and extending quantitative homogeneity within the circulation and distribution process, but also by exploiting distraction through cultural consumption, above all by promoting qualitative differentiation through the processes of design, production, and marketing. Consider, for example, the corporate brand campaigns of Gap or Nike, or the predatory intellectual property tactics of Google and Microsoft. In each case, trademarking, patenting, and copyrighting entail not just the classic industrial marketing of commodities for commercial profit, but also the postmodern promotion of lifestyle images and the proliferation of bits of cultural information through various media. At the same time as a financial profit is acquired and invested, a symbolic premium is productively consumed to achieve a comparative advantage at the level of “sign-value,” or “difference-value,” in spite (or even because) of occasional outrage over sweatshop labor or copyright infringement at the design and production stage (Klein 2000). At stake in the escalation of these competitive struggles is not just the circulation of goods and money but also the communication of meanings and values, just as the object of capitalist desire is no longer simply the commodity-fetish, which draws on a fantasy of abundance, but also the technology-fetish, which projects a fantasy of participation (Dean 2005). In other words, the production and distribution of material and cultural wealth increasingly comes to rely on the interpellation of information and the call of communication by transforming (apparently autonomous) individuals into (actually dependent) subjects in the process (Althusser 1971, 182). This capitalist culture of distraction is driven in turn by the imperative of mobility and the compulsion of accelerated adaptability: “Thus there appear to be innumerable relations of exploitation based on mobility differentials: financial markets versus countries; financial markets versus firms; multinationals versus countries; large principal versus small subcontractor; world expert versus firm; firm versus casual workforce; consumer versus firm” (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005, 371; italics added). Within the new networks of global capitalism, flows of wealth, power, and information are conveyed through channels which are both local and remote, instantaneous as well as mediated, and which produce simultaneously short-term and far-reaching effects. Simply put, the emerging “knowledge economy” is not just a catchword for the “soft, virtual, and fast capitalism” of the information, communication, and technology (ICT) sectors (Agger 2004; Thrift 2005), but above all a fundamental mutation in the investment, production, accumulation, and consumption processes of capital itself.

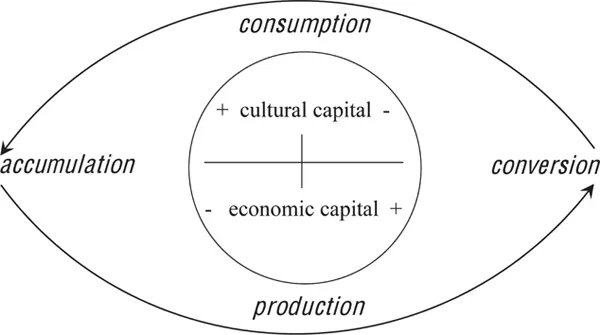

With this argument in mind, we need to download and update Marx’s “general formula for capital” and his “law of capitalist accumulation” to account for how the processes of production and consumption, accumulation and conversion, are integrated into the socio-technical circuitry of the new media and the flows of speculative finance (see Haiven, chapter 3; Sully, chapter 6). Figure 1 (below) depicts how the reflexive and reticulated circuits of money (M) and commodities (C) are networked into the ordinary time-space of lived experience and everyday communication in the modern world. As Marx argues in Capital I (Marx 1977, 247–80, 762–802), in theory the surplus value of any commodified good may be productively consumed, preserved, destroyed, or accrued at any point along the chain of capital formation, from the points of entry to exit and between the levels of substructure and superstructure (the vertical axis of Figure 1). A surplus (marked here as M-prime and C-prime) is only realized (or valorized in Marx’s terms) at the point of sale (for example, when the commodity is converted into cash at the top or end of the cycle, or when some thing or idea is bought and successfully marketed); or surplus value may be preserved and accumulated insofar as it is stored or reinvested at the bottom or beginning of the cycle (such as when raw materials, labor power, or technologies are acquired, purchased, and productively consumed). By depicting Marx’s classic formula in this way, I mean to draw attention to our commonsense understanding of how capital operates by mobilizing “the little things” (Thrift 2000): namely, by integrating mundane objects, activities, texts, images, and words into simple everyday transactions which facilitate the relations of ruling of capital and mediate complex chains of commodification and communication (Smith 1999). In the course of these exchanges, the depths of our ‘technological unconscious’ tend to become more vast as their material and economic foundations recede from view. As a result, “we may … be witness to a kind of evolution of the commodity which, in turn, is dependent on the evolution of everyday spaces which will endow them with an interactive awareness” (Thrift 2005, 193). As the separation of business enterprise from household activity, which Weber considered to be a defining historical precondition of industrial capitalism, becomes increasingly strained and blurred, the divisions between the private self and its public display seem to erode or collapse altogether.

FIGURE 1 Capital I

(cf. Marx 1977, 247–80, 762–802)In a literal sense, then, we might imagine this “Capital I” to trace not just the “dream-work” and “design-ingenuity” to which the macro-processes of capital-innovation are increasingly subject; it also represents the micro-dynamics of self-formation through social networking which are the fate of individuals “linked in” to the ubiquitous interfaces of the new social media. Here it is useful to recall Simmel’s insights into how the money economy breaks open relatively smaller, more insular, and uniform circles of traditional society both by facilitating social expansion and by intensifying individualization:

Stimulations of the feelings on which the larger group is dependent for the subjective consciousness of the “I” occur precisely where the very differentiated individual stands amidst other very differentiated individuals, and then comparisons, frictions, specialized relationships precipitate a plethora of reactions that remain latent in the narrower undifferentiated group, but here provoke the feeling of the “I” as what is quintessentially ‘proper’ to the self through precisely its fullness and diversity. (Simmel 2009, 664; 1992, 848; translation modified)

As Simmel notes specifically with reference to life in the modern city, the escalation of intensified interactions and continuous communications forces the individual to cultivate a kind of “protective organ,” in the form of mental discipline or intellectual concentration, for example, or perhaps today with the help of some technological prosthesis such as the automobile or iPhone. Such techniques of distraction and distinction filter the stream of stimuli and control the overload of signifiers while extending the physical and virtual boundaries between the self and its surroundings. “A person,” Simmel writes,

does not end with the limits of his physical body or with the area to which his physical activity is immediately confined but embraces, rather, the totality of meaningful effects which emanates from him temporally and spatially. In the same way the city exists only in the totality of the effects which transcend their immediate sphere (Simmel 1971, 335)

As the modern metropolis morphs into mass media, individual identity becomes subject to the perpetual play of sensation and imagination, and the reality of distance is concealed behind the appearance of immediacy. Ruled by this iconographic logic of speculation, surplus value takes on the form of tele-value (TV), at least insofar as culture-at-a-distance is capitalized, with commerce merging with aesthetics and finance being transformed into fantasy (Kemple 1995, 163–4).

With these points in mind, we need to revise Marx’s notion of the fetish-character of the commodity (Marx 1977, 163–77) to account for how images and things seduce us into closing the ideological gap between the visible and invisible society: “The commodity fetish is a talking, seeing, feeling god inviting us into the liturgy of consumption to dispel the sorrows of production” (O’Neill 2002, 172). As John O’Neill suggests, capital has learned to operate by de-institutionalizing the self and re-assembling its identities, if not by coercive restraints then through the softer stimulations of remote-control, so that the individual comes know itself through the mirror of the media: televideo ergo sum. Insofar as the classic disciplinary institutions of modernity—the school, the factory, the hospital, and the factory—no longer function effectively to confine bodies and mold minds into responsible and motivated individuals, technologies of the self must step in to induce desires, inspire ideas, and inform imaginations which can then be packaged and distributed through exploitable networks: “Individuals become ‘dividuals’ and masses become samples, data, markets, or ‘banks’” (Deleuze 1995, 180). As if to extend points made by Marx and Si...