![]()

1

Soft Power in Transboundary Water Governance

The management of international rivers has become increasingly problematic due to the state of freshwater water today – the only scarce natural resource for which there is no substitute (Wolf, 1998), and one which fluctuates in both time and space (Giordano and Wolf, 2003). As a result, ‘water’ and ‘war’ are two topics that have been assessed together at great lengths. Water disputes have indeed been labelled as one of the ‘New Wars’ in Africa, comparing it to the likes of other ‘resource wars’ such as those over oil and diamonds (Jacobs, 2006). Thus, there is a great fascination with the notion of a ‘water war’, and while there is evidence to the contrary and the debate over ‘water wars’ won in favour of cooperation (Jacobs, 2006; Turton, 2000a, 2000b) this argument still rears its head time and again.

Norms and trends in the water conflict discourse

The perception of water as a source of international warfare is pervasive not only in the public mind but also in political circles. In 1985, former Secretary General of the UN, Dr Boutros Ghali, uttered the now (in)famous words: ‘The next war in the Middle East will be fought over water, not politics.’ Academic literature on water resources as well as popular press are filled with similar sentiments, particularly as a result of the real or perceived impact that increased scarcity may have on socio-economic development and the lives of people all over the world. Furthermore, the scarcity of water in an arid and semi-arid environment may lead to intense political pressures, or to what Falkenmark (1989) refers to as ‘water stress’. The Middle East is considered to be the ideal example of this, where armies have been mobilized and water has been cited as the primary motivator for military strategy and territorial conquest. However, this territorial argument, based on a state’s desire to obtain water beyond its borders, is limited when one considers the nature of water-sharing agreements, particularly over the use of the Jordan River between Israel and its neighbours. As part of the 1994 Treaty of Peace, Jordan is able to store water in an Israeli lake while Israel leases Jordanian land and wells (Giordano and Wolf, 2002). This example reflects the ability of states to cooperate without the desire to conquer territory, particularly in a politically contentious region.

Since the allocation of water has often been closely linked with conflict situations, there has been a tendency to rely on history (by reinterpreting history in a way which justifies a conflict potential) as proof of water’s ability to cause interstate war (Church, 2000). Arguments such as these, however, isolate specific cases in which water becomes embedded in sociopolitical, economic, cultural or religious tensions, and are therefore used as (falsely) justifiable reasons for going to war. For example, Church refers to the early 1950’s dispute between Syria and Israel, where sporadic fire was exchanged due to the Israeli water development in the Huleh Basin (ibid.). But the author questions the degree to which this dispute can be classified as a water war, since the causal relationship between water and war is greatly obstructed by ethnic, cultural and religious tensions that existed between these states (ibid.). This leads one to ask the question, what really was the cause of the war? The unsuccessful military expedition by Egypt into disputed territory between itself and Sudan in the late 1950s is another (mis)-cited example, and again, begs the question, what really was the cause of the conflict – water or a disputed territorial boundary? According to Church, this suggests that history does not provide the clear-cut lesson upon which contemporary literature relies (ibid.).

Some scholars have also argued that the problems of water management are compounded in the international arena by the fact that the international law regime that governs it is poorly developed, contradictory and unenforceable (Giordano and Wolf, 2002). Analyses based on this argumentation, however, ignore the fact that there are more water agreements in the world than there are, or have been, water-related conflicts (ibid.).1 Despite the obstacles riparian states face in the management of shared water resources, these very states have demonstrated a remarkable ability to cooperate over their shared water supplies.2 However, analyses cautiously point out that despite the lack of interstate warfare, water has acted as both an irritant and a unifier. As an irritant, water can make good relations bad, but is also able to unify riparians with relatively strong institutions (Ashton, 2000a, 2000b; Wolf, 2005).

Water’s ability to increase interstate tensions is most prevalent in the debate between sovereignty and equitable distribution of shared water resources. Underlying this is the contradiction between the compartmentalization of states who claim sovereignty rights over resources in their territory versus the indivisible and uninterrupted continuum of water (Westcoat, 1992). The question here is simple: can a country use its water as it pleases? This results in a clash of two global norms, that is sovereign ownership and exclusive rights over one’s resources versus the principle of shared ownership and equitable utilization of an international river. Depending on which side of the debate states sit, either the securitization of water as an issue of high politics and national security is prioritized, or the desecuritization of water as an issue to be debated in the public domain wins out.

In current debates, there are those who focus on the regional (and global) conflict potential of accelerating environmental problems such as drought and sea-level rise. Here, the Malthusian discourse is noteworthy. It hypothesizes a linear relationship between population growth and scarcity. Malin Falkenmark is instrumental in this regard, for developing the ‘water scarcity indicators’, based on the central notion of a ‘water barrier’ (Falkenmark, 1989: 112). Her thesis postulates that as populations increase, so too does water scarcity, which leads to competition and potential conflict. This type of theorization then led other authors to conclude that the inherent linkages between water scarcity and violent conflict predicted the inevitable occurrence of water wars in the twenty-first century.

Homer-Dixon, the most prominent author on the subject of scarcity and conflict, outlines three major sources of environmental scarcity and their interaction (Homer-Dixon, 1994). First, supply-side scarcity describes how the depletion and pollution of resources reduce the total available volume. Secondly, demand-side scarcity explains how changes in consumptive behaviour and a rapidly growing population can cause demand to exceed supply. And thirdly, structural scarcity occurs when some groups receive disproportionably large slices of the resource pie, leaving others with progressively smaller slices (Turton, 2000a). Homer-Dixon does, however, acknowledge that environmental scarcity is never a conflict determining factor on its own, and is usually found in conjunction with other more detrimental causes (Homer-Dixon, 1994). As such, environmental scarcity can aggravate existing conflict and make it acute. In southern Africa, this plays out when marginalized communities are forced to migrate and settle on contested land, thereby bringing these incoming communities into conflict with people who are already struggling to survive. Migrations away from the Kalahari towards the panhandle of the Okavango Delta, and urban migration towards Windhoek in Namibia, are two such examples.

Then, there are those who see environmental degradation as an opportunity for social ingenuity, conflict prevention and management. Leif Ohlsson argues that as water scarcity increases, so too does the need for social adaptation to the consequences of this scarcity (ibid.). With increased desertification or the greater frequency of droughts, lifestyles have been forced to adapt and social patterns have been forced to shift. Ohlsson also distinguishes between first-order resources, and social or second-order resources. Adaptive capacity is therefore determined by the degree to which some states that are confronted by an increasing level of first-order resource scarcity (scarcity regarding the resource, that is water) can adapt to these conditions provided that a high level of second-order resources (social adaptive capacity or what Homer-Dixon refers to as ‘ingenuity’) are available.

Still, other scholars oppose any causal linkages between scarcity and war (as opposed to conflict). Anthony Turton defines a water war simply as a war caused by the desire for access to water. ‘In this case, water scarcity is both a necessary and sufficient condition for going to war’ (ibid.: 36). Turton therefore identifies ‘pseudo’ wars as those conflict events that take place when hydraulic installations such as dams and water treatment plants become targets of war. A war in this category is thus caused by something quite unrelated to water scarcity, and is therefore, not considered to be a true water war, but rather a conventional war, with water as a tactical component.

Furthermore, when rivers form part of contested international boundaries, they may also be the focal point of war as water issues become politicized. In this case again, water scarcity is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for going to war (ibid.). One example is that of the military confrontation that broke out between Botswana and Namibia over the control of an island (important for grazing) situated in the contested boundary area of the Chobe River (Breytenbach, 2003). As such, water as the cause of war is a very narrowly defined condition, with limited empirical evidence of its existence over time. Most authors, arguing for the increasing threat of water wars, are often misled when labelling conventional wars as water wars, or exaggerating the threat of a dispute escalating into military aggression.

Norms and trends in the water cooperation discourse

Norms and trends in water therefore originated largely in an attempt to eradicate or minimize real, perceived or predicted conflicts (Jacobs, 2010a). The global norm set of transboundary cooperation is arguably the most prominent, comprising of principles such as equitable and reasonable utilization, the no harm doctrine, information exchange, consultation with other riparian states and ecosystem protection. This norm set has evolved over time into its current form because of the need to reconcile the tension between shared river protection and the rights of states to utilize their water resources as they see fit.

Criteria for normatively assessing ‘good’ and ‘bad’ practice in transboundary water management

Global fatigue

It can certainly be argued that the need to accommodate the multiplicity of demands on water, has led to an ‘institutionalized’ way of knowing and dealing with water (Lach et al., 2005) that is considered to be normatively ‘good’, driven largely by influential state and non-state actors of the North. Research conducted on the degree to which global norms have diffused to lower levels of scale raise the question of the appropriateness of these global norms to different contexts, which are often accepted rather uncritically as a goal for which to strive. Described by Acharya (2004) as the first wave of normative change, these analyses tend to give causal primacy to ‘international prescriptions’ and in so doing, often undermine the important agential role of ‘norms that are deeply rooted in other types of social entities – regional, national, and sub-national groups’ (Legro, 1997: 32). As Checkel observes, this focus on the global scale, creates an implicit dichotomy between what is considered to be ‘good’ global norms, seen as more desirable and ‘bad’ regional or local norms (Acharya, 2004; Checkel, 1999; Finnemore, 1996; Finnemore and Sikkink, 1998). Analyses that take this stance often perpetuate a biased moral superiority of the ‘global’, by regarding global norm diffusion as a process of ‘teaching by transnational agents’, which downplays the agency role of local actors (Acharya, 2004).

If the global norm set was in fact the most appropriate standard to be emulated in water agreements at lower levels of scale, and applicable to all contexts, then there would be evidence of easy and exact diffusion of the entire norm set at regional, basin, sub-basin and national levels. The fact that several norms found in the global norm set of transboundary cooperation are at times inappropriate or inapplicable to particular (and specifically developing country) contexts is reflected in the ineffectiveness of many international environmental agreements, as a result of powerful actors who impose foreign norms onto local contexts, for instance, as lip service rhetoric to external donors or other international institutions. At best, these norms are manipulated and transformed into a context-specific code of conduct, but may also become institutionalised in their globally relevant but locally inapplicable form. In essence, “bad” (or inapplicable) norms become institutionalized too. Similarly, that which is considered to be best practice is in most cases, context specific. There is therefore, not one set of criteria for normatively assessing ‘good’ and ‘bad’ practice in transboundary water governance.

Cooperation versus environmental multilateralism

It is also important to emphasize that cooperation and environmental multilateralism are not one and the same. Additionally, they are often regarded as the ideal despite producing sub-optimal outcomes that is vacuous institutions. Indeed, policymakers have used these terms interchangeably as if referring to one concept. It should be emphasized at the onset that multilateral institutions have increased in the past three decades (Meyer et al., 1997) but this has not necessarily led to ideal cooperation between states or effective regimes that are intended to provide governance (Dimitrov, 2005). Riparian cooperation is celebrated for its potential to produce benefits to the river, from the river, because of the river and beyond the river (Sadoff and Grey, 2002, 2005). However, the extent to which riparian interactions actually produce such benefits has been widely overlooked by the international water community. The persistence of such oversights contributes to a growing stream of well-intentioned but misinformed policy. Moreover, norms, institutions and governance are not conterminous despite being treated as such in existing scholarship (Dimitrov, 2005). This neo-institutionalist assumption stems from the premise that institutions are instruments for providing governance, and norms serve as the basis for both (ibid.).

The conflict-cooperation problematique

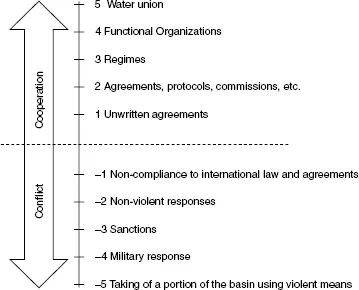

Research and evidence has proven that while there is an unlikely probability of interstate water wars (conventional warfare) erupting in the future, the lack of cooperation does carry security implications and sub-optimal water management strategies. Yet even this focus is misleading, for there is a danger in interpreting it to imply a normative appropriateness towards unprecedented cooperation and the sharing of international freshwater supplies. Framing the debate in this way places the concepts of cooperation and conflict on a continuum, as an all-or-nothing outcome, with cooperation existing as an extreme in direct opposition to war as depicted in Figure 1.1 (Sadoff and Grey, 2005).

Figure 1.1 The conventional cooperation-conflict continuum of cater (adapted from Meissner, 2000a)

Although not explicitly indicated in most analyses, most literary contributions to the hydropolitical discourse subscribe to the neo-realist notion of an anarchical or ‘governless’ international system, in which state behaviour is not only the product of state attributes themselves, but also of the structure of the international system within which these interactions take place (Du Plessis, 2000). But it is also believed, under a neo-liberal institutionalist perspective, that cooperation and collaboration are possible (and necessary or even inevitable) under conditions of anarchy through the establishment of formal cooperative regimes/institutions. This problematique between peace, stability and progress is a fragile and very important one, because the emphasis is on the potential for ‘water wars’ based on the threat water-related contingencies pose to security (Du Plessis, 2000). These approaches prioritize the inevitability of either water conflict or water cooperation (in the form of ideal multilateral collaborations).

As such, a linear continuum between conflict and cooperation is often conceptualized and the formation of institutions and regimes ranging from informal to formal are the rungs by which to measure success, that is cooperation (see Figure 1.1). Similarly, a linear transition from ‘water wars’ to ‘water peace’ is implied in several scholarly works (Allan, 2001; Ohlsson and Turton, 1999). In this regard, scholars have argued that Africa’s transboundary rivers could become either drivers of peace and economic integration or sources of endemic conflict (Turton, 2003a). Cooperative management of shared watercourses has therefore been trumpeted as the ideal, since it can optimize regional benefits, mitigate water-related disasters and minimize tensions.

But as Warner (2012) argues, the water wars thesis painted too gloomy a picture, but in parallel, the water cooperation thesis was overly optimistic to resonate with context-specific realities. In practice, cooperation and conflict coexist. Or as Brouma (2003) explains, water issues are highly politicized and securitized, but also simultaneously constitute an element of cooperation. Indeed, the logic argued here is that the conflict-cooperation problematique is one in which degrees of conflict and cooperation regarding transboundary waters can occur simultaneously. The type of cooperative strategy negotiated should therefore be unique to a particular context.

Best practice from the North?

Additionally, current studies focus on the need to develop appropriate scientific/economic methodologies that can explain and predict future patterns of conflict and cooperation (Turton, 2003a, 2003b, 2003c, 2003d). Technocratic templates from Europe and North America, such as the concept of integrated water resources management (IWRM),3 have also been suggested as best practice. However, not enough attention has been placed on factoring in local configurations, domestic policy, political identities and social and cultural institutions, particularly in the African context.

Developing a community of interest

What is lacking in hydropolitics literature is how we get to this state of cooperative management (the practicalities thereof), and which types of cooperative strategies are best for each region and river basin. Indeed, transboundary river basins and the management thereof occur within coexisting conflictive and cooperative dimensions, with actors cooperating on a particular aspect (e.g. information exchange for instance) and not cooperating or ‘fighting’ over another (e.g. the volumetric allocation of water).

The normative frameworks within which regions and transboundary river basin management exist are therefore critical to understanding the conflict-cooperation problematique. A central question in this regard relates to the convergence and/or resistance of norms and values around issues of governance, and particularly cooperative management in these shared ecosystems (Conca, 2006). Recently too, cooperation has begun to be viewed more broadly than just an outcome of the sharing of volumetric allocations of water. Policymakers have now begun to see transboundary cooperation as the way to jointly identify development options and socioeconomic benefits that can be achieved in a transboundary and multilateral context.

This benefit-sharing4 paradigm instigated by cooperative management strategies has implications for normative frameworks and vice versa. Can norms on water-sharing5 evolve into a benefit-sharing normative framework6 where actors begin to believe that the benefits of cooperating transcend merely sharing volumetric allocation of water but include benefits of regional integration, such as economic development and sociopolitical benefits? To what degree does norm resistance affect this dynamic? One w...