![]()

1

Occupational hazards and sporting catastrophes

It’s a bit funny but we are a dying breed paying homage to the already dead. Well we are, there are none of us to follow...People of Swinton and Pendlebury, please tell your children about us, tell them about those who have gone before, of the blood, sweat and tears they shed in order to make this a better place, take them on the heritage trail so thoughtfully provided by your council. The mining families of the past fought, suffered and died for the rights we now enjoy, please don’t let them down.

Brian, father of Adam Stott (336), the last miner to die at Agecroft Colliery, Swinton. 29 May 2016

At 9.20am on Thursday 18 June 1885, for some, time stood still. A huge explosion occurred at Clifton Hall Colliery, near Swinton, Salford that could be felt at a distance of half a mile (0.8 km). In total, 178 men and boys were killed through injuries, burns, drowning or by the effects of ‘afterdamp’ (carbon monoxide poisoning). The bodies of the miners were buried at numerous churchyards and burial grounds in the locality, including the Jane Lane burial ground, which was subject to commercial development in 2013, some 130 years later. The human remains in the burial ground pre-dating 1900 were not cleared away but instead were exhumed and recorded by archaeologists prior to reburial in Swinton cemetery, forming one of our study groups for this project. Through this process the remains of some of the victims of the Clifton Hall Colliery disaster were identified and its history once more brought to light. Unfortunately, incidents like these were all too common during this period, a time of industrial accidents on an industrial scale. Construction projects were implemented at a furious rate during the Victorian period and were notoriously dangerous. It has been calculated, for example, that three labourers died for every mile of rail track laid in the UK. Mortality rates were even higher for the railway tunnellers. Thirty-two labourers were killed and at least 140 seriously injured while working on the Woodhead Tunnel between Manchester and Sheffield, which runs for 3 miles (4.8 km). That’s one death plus 4–5 serious injuries for every 495 ft or 150 m.

Accidents, of course, were not just restricted to the work-place. Cities like London were energetic places of hustle and bustle, people constantly on the go, with no time to waste and ever in haste. The lack of regular maintenance checks and health and safety regulations meant that the potential for danger lurked on every corner and not only in the towns; roads everywhere were a source of constant threat, especially with the use of horse-drawn carts on pot-holed tracks. Road safety was not a concept and nor was there any lawful responsibility on the part of the builders of temporary constructions, machines or contraptions, which many people used in the home or as part of recreation on a daily basis. Some injuries, of course, were also sustained through acts of violence resulting from wars, domestic abuse, or ‘Peaky Blinders’ style rival gang brutality. Others were caused by common sporting activities such as horse riding, boxing or shooting. The recording of traumatic injuries in skeletal remains by archaeologists, supplemented by historic accounts of events happening at the time, gives us a very stark reminder of the scale of unfortunate misdemeanours and human disasters that occurred in the past and how this compares with our heavily safety-regulated living environments today.

London is nowadays associated with high levels of accidents and violence on account of the high population density and sheer volume of vehicular traffic in the City. Was this also the case in the past? Was life in the City really more hazardous compared to more rural settings? How did accidents and trauma impact upon our bodies in the past and was this different according to where we lived?

Pre-industrial lifestyles and trauma risk

Trauma is predominantly influenced by the environment in which we live and work, and the medieval period in Britain was no exception. During this time the country was predominantly agricultural and jobs were labour intensive. For many, food production, brewing and farming were day-in, day-out tasks of hard, manual labour. This would have extended to the maintenance and repairs of their own houses, barns or other property. Occupational hazards, then, were surprisingly common, even within rural settings.

Some of the more risky environments would have been experienced by the raft of tradesmen specialising in jobs that were more industrial in nature, such as carpentry, candle making, milling, brick and tile production, quarrying, mining, cloth making, smelting and blacksmithing (Fig. 24). As the population grew throughout the medieval period not only did the agricultural economy intensify, with more and more land cleared for crop growing, but also technologies involving the production of foods, materials and transport advanced. The 6500 turnable mills already in existence in England in 1086, as documented in Domesday Book, were quickly superseded by vertical windmills, the earliest of which in Europe is thought to date to 1185, located in the former village of Weedley in Yorkshire, overlooking the Humber Estuary. The wide-ranging major technological advances and inventions in medieval Europe from the 12th century led to the mechanisation of many production processes, although these industries were still in their infancies compared to the vast scale of mass production experienced from 1750 onwards in England.

Figure 24 Recreating medieval blacksmithing.

(Hans Splinter, cc-by-nd/2.0, https://www.flickr.com/photos/archeon/10493442664)

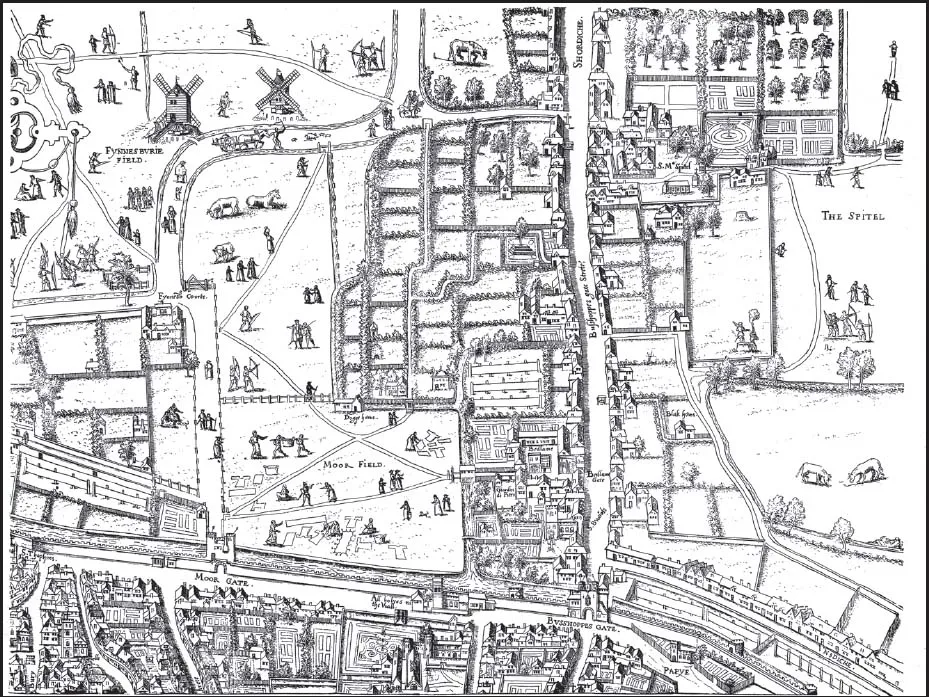

Figure 25 Copperplate map 1559, Frans Franken, section showing Moorfields and The Spital

(© Museum of London)

Figure 26 Cheese merchant at market and textile dyer

(Paul K. cc-by/2.0, https://www.flickr.com/photos/bibliodyssey/albums/72157610727752183)

Towns, and even cities such as London, were much smaller and less densely populated than today. Many areas in the City during the medieval period, such as Nine Elms, Bow, Hackney, Bethnal Green, Chelsea and Spitalfields, were small hamlets, villages or bases for religious houses, surrounded by open greenfields used for market gardening, agriculture and meadowland (Fig. 25).

Over time, as trade between settlements grew and more goods were transported by land and by river, the market economy developed (Fig. 26). Markets in towns flourished, and those in the City such as Billingsgate, where originally many goods such as corn, coal, iron, salt pottery and fish could be purchased, eventually specialised; Billingsgate for example became the world famous fish market.

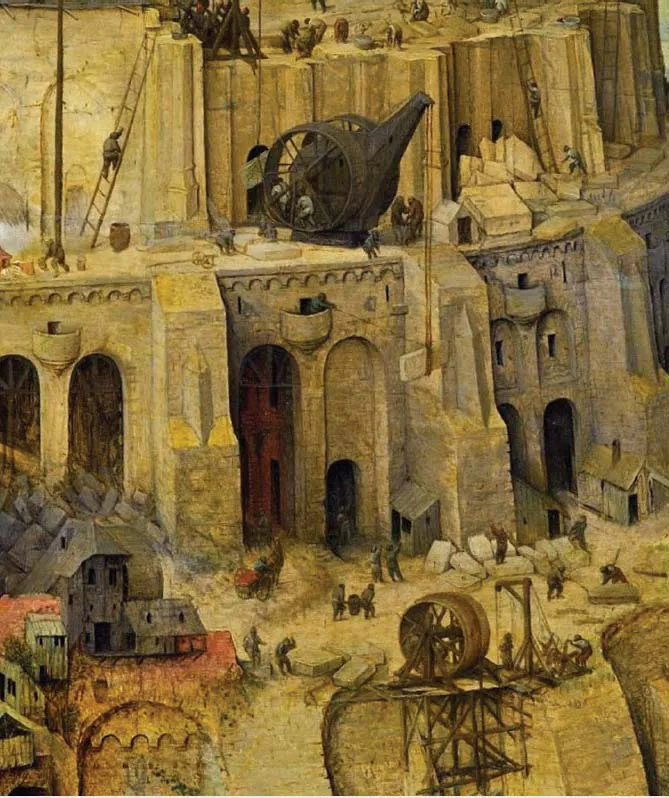

The market wealth generated led to the construction of an increasing number of prestigious large stone buildings, in particular, strongholds and cathedrals, as well as bridges. The building of Westminster Abbey, completed in 1066, and West Minster Hall, started in 1097, not only consolidated the position of William the Conqueror as the King of England but also London’s status as the political and mercantile centre of the country. The City’s higher status and clerical role led to the creation of many bureaucratic and professional occupations. The construction trade, in contrast, was very hazardous, with little to protect workers from substantial falls and injuries (Fig. 27).

Figure 27 Bruegel’s Tower of Babel, detailing stone construction and use of the treadmill crane

(rpi virtuell, cc-by/2.0, https://www.flickr.com/photos/84132860@n03/7702914260)

Written accounts at St Paul’s Cathedral, dating to the time of Sir Christopher Wren’s construction from 1675, record compensation payments to the widows of builders who died from falls at the site. Additionally, analysis of the medieval human remains from Hereford Cathedral, carried out by the University of Bradford, revealed a high number of fractures, including multiple injuries and crush fractures among males, likely related to the contemporary building works in the city of the Cathedral and the castle, although these were healed fractures, indicating that the injuries sustained were not fatal.

Also present at Hereford Cathedral, as found elsewhere such as at Barton-upon-Humber, Wharram P...