eBook - ePub

Tragedy of Lebanon

Christian Warlords, Israeli Adventurers, and American Bunglers

- 338 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

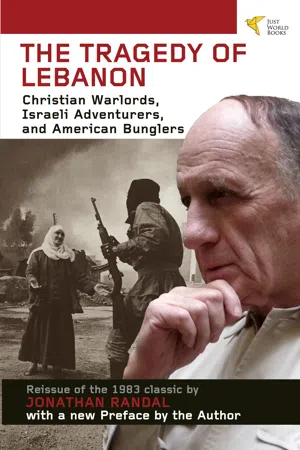

The Tragedy of Lebanon is a reissue of Jonathan Randal's acclaimed 1983 study of the rightwing Christian militias in Lebanon that in 1975 plunged the country into a decades-long cycle of war and civil conflict. For this 2012 reissue of the book, Randal added a piercing new Preface reflecting on the meaning of those events, both then and today. As the Senior Foreign Correspondent of The Washington Post, Randal covered Lebanon intensively from 1974 through 1983, having already reported from Vietnam and several other war zones. The Tragedy of Lebanon shows his powers of observation, astute analysis, and storytelling at their very best.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tragedy of Lebanon by Jonathan Randal in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Miracles and Hallucinations

When they finally dug him out of the rubble six hours later, what was left of Lebanese President-elect Bashir Gemayel had turned almost blue. The back of his large head was missing, as was most of the back and buttocks. “It’s Bashir,” said Karim Pakradouni, recognizing the prominent nose, the dimple in the chin, the hexagonal wedding ring, even before extracting a note from the breast pocket of the bloodstained safari jacket. This turned out to be from the nuns of La Croix psychiatric hospital, invoking the Virgin’s protection; Gemayel had lunched with them. That clinched the identification for Pakradouni. But one of the six doctors in the emergency room at the Hôtel-Dieu hospital in East Beirut argued with Gemayel’s close political adviser. The doctor knew perfectly well that clinically Bashir was dead. But he didn’t dare say so, didn’t dare have Pakradouni say so. For Pakradouni would have to tell the world the truth. The doctor would have preferred Pakradouni to remain silent, to freeze time. “No, Karim,” he said, “you have a grave responsibility.”

Pakradouni paid the doctor no mind, but he did discharge his responsibility as he saw fit. He drove his Range Rover, the supreme Lebanese status symbol, back to the windowless concrete bunker headquarters of Gemayel’s Lebanese Forces militia near the port. With Fady Frem, the freshly appointed commander of Gemayel’s private Christian army, Pakradouni issued orders banning guns on the street and restricting the Christian militiamen to barracks. That was a normal reflex after seven and a half years of violence.

Whoever killed Bashir Gemayel—and there was no dearth of candidates, given the young President-elect’s record of murdering his way to the top—would be hoping for an extra dividend in the form of mass reprisals. These regularly occurred in Lebanon after assassinations of political leaders. More than 300 pro-Gemayel Christians had died in retaliation for the 1978 assassination by Bashir’s men of Tony Franjieh, elder son of the former President of the Republic, Franjieh’s wife and daughter, and thirty-one of his partisans. In 1977 the Druze Moslems slaughtered more than 170 Christians in the Shuf Mountains, south of Beirut, after their leader, Kamal Jumblatt, had been assassinated by Syrian agents. The Lebanese Forces and the Syrians were then nominal allies, but the Syrians had nearly thirty thousand troops in Lebanon, ostensibly keeping peace, and they were too strong for the Druze. In Lebanon you slaughter those you can, not necessarily those you’d like to. Lebanon is not a country where even the most innocent and minor hurt or error is forgiven or forgotten.

But the last thing Pakradouni wanted in the Christian ghetto was militiamen running amok, seeking revenge. More than one hundred thousand Moslem Lebanese who had fled West Beirut during the long Israeli siege were still living in what the Lebanese Forces called their “liberated region”—in contrast with the 85 percent of Lebanon they did not control. Frem and Pakradouni were convinced the Lebanese Forces’ elementary precautions were all the more called for since collective hysteria might well follow the mass hallucination that had gripped so many Christian Lebanese that Tuesday, September 14, 1982. The distraught doctor at the Hôtel-Dieu was not the only one who preferred to deny Bashir Gemayel’s death. The prospect of Gemayel’s impending six years in office solved a variety of problems for a variety of interested parties, domestic and foreign.

Israel had carefully cultivated Bashir Gemayel for years, providing arms and training for his men and invaluable help abroad in his uphill struggle for international respectability. Israel had invaded Lebanon on June 6 for its own reasons, and without the Lebanese Forces’ political support and rear-base facilities it is doubtful whether Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Defense Minister Ariel Sharon would have dared launch the operation. But another important Israeli calculation was aimed at electing their protégé to the presidency of Lebanon and ensuring a friendly, Christian-dominated regime there.

The United States was a late convert to Bashir Gemayel’s cause. Indeed, the United States came to back him faute de mieux and not without second thoughts, as befitted a superpower wary of Gemayel’s methods (which included an attempt on the life of an American ambassador) and skeptical of the durability of a man intent on reasserting Christian domination over Lebanon’s Moslem majority.

The Lebanese Moslem leaders were resigned to Gemayel, if not volubly enthusiastic about him. Gemayel denounced Lebanon’s occupation by Palestinians and Syrians, but the Moslems, not the Christians, had to live with them and their protégés. Along with the now-departed Palestine Liberation Organization, they were the ostensible losers in Israel’s summer war of 1982. Their flock was willing to forget its past opposition to Gemayel if he made good on his promise to restore order and get rid of the dozens and dozens of parties, militias, and neighborhood gangs that had reduced life in West Beirut and much of Lebanon to anarchy.

The explosion, which took place at 4:08 p.m., Tuesday, September 14, sent a huge yellow-brown cloud of dust and smoke billowing above the three-story building that housed the main East Beirut branch of the Phalange, the political party founded by Bashir’s father, Pierre Gemayel, in 1936. Bits of arms, legs, shoulders, and heads were strewn among the collapsed pillars, concrete rubble, stone, and metal. The street was filled with cries of “Bashir! Bashir! Bashir is inside!” One militiaman pounded the street in frustration. Others took their fury out on the press, confiscating film, beating, even shooting at, photographers. Ambulances and medical teams stood by. Party officials and Bashir’s wife, Solange, arrived and waited.

A creature of habit, grown careless in the euphoria of his recent election, Gemayel had refused to call off—or vary the timing of—the meeting at the party headquarters where he had first broken into politics and which he regularly attended every Tuesday afternoon. Even as President he planned to return here often to speak and listen to the taxi drivers, shopgirls, housewives, and old-age pensioners seated on simple wooden chairs drawn up in rows in the ground-floor foyer; it was decorated with photographs chronicling his father’s long march to power, now symbolized by his own success. “This is the Levant,” he told me in that building, years ago, when I first got to know him. “You have to answer the telephone yourself—no secretary—listen to each conversation, and receive each visitor. That’s how you get people to trust you and find out what they are thinking.”

Watching the rescue workers, Pakradouni, increasingly worried, asked a doctor how long a man could be expected to live under the rubble. About two hours, he was told, a judgment that soon made the rounds. By six o’clock it was dark. The tension was unbearable. The young rescue workers labored faster and faster under arc lights. Suddenly, a man in a safari jacket was extracted from the wreckage and rushed into an ambulance, which was driven off at breakneck speed. The crowd cheered wildly, shouting, “Bashir! Bashir!” There seemed to be no doubt: the President-elect was safe. What baraka! What divinely inspired luck! Even as experienced a correspondent as Lucien George of Le Monde was convinced he had “seen” Bashir being helped into the ambulance. A helicopter flew overhead, but was driven off by the random shooting. Friends in the crowd reassured one another that the Israelis had sent the helicopter to take Gemayel to a hospital in Israel. The Voice of Free Lebanon, the pirate radio of the Lebanese Forces, commonly called Radio Bashir, quoted the President-elect as thanking the Good Lord for having spared his life, and reported that he had gone home to change clothes, since his only injury, a bruise on his left leg, did not require hospitalization.

Relieved, Solange and Pakradouni left, and drove down the steep hill to the Hôtel-Dieu. Bashir was not there, they were told. Still confident, they rushed to the Rizk Hospital, where they were greeted by Dr. Assaad Rizk. Bashir was not there, he said.

“Don’t play games with me,” Pakradouni barked.

“Are you crazy, Karim?” the doctor replied. “Do you think for a second I would dare joke about Bashir?”

It was almost 8:00 p.m. Only then did Solange and Pakradouni realize that Bashir was still under the rubble—and very likely dead. That was a calculation that various embassies had made hours earlier, when they sent staffers to look at the wreckage. Pakradouni returned to the party building. Rescue workers, still convinced Gemayel was safe and sound, slapped him on the back and joked with him. Pakradouni did not have the heart to tell them the truth. Gemayel’s stocky body was one of the last to be removed, just after 10:00 p.m., and finally taken by ambulance to the Hôtel-Dieu.

Prime Minister Shafik Wazzan announced the President-elect’s death at midnight. But hours earlier the public had surmised the truth. The evening television news was dispatched in barely three minutes. For the first time since the killing started in Lebanon on April 13, 1975, Beirut Radio interrupted its usual pop fare to play classical music. None of the previous seventy-five thousand victims had warranted such a mark of respect. It broadcast classical music for a week.

The somber music, meant for Gemayel alone, might have been dedicated to others as well. His assassination ushered in a week surpassing everything Lebanon had managed to provide by way of violence, horror, and mindlessness; it further undermined American credibility in the Middle East, sullied Israeli honor, and added yet another unwanted chapter to the liturgy of Palestinian martyrdom.

The music also interrupted many Lebanese Christians’ collective hallucination. This temporary suspension of disbelief corresponded to a genuine reluctance to accept Bashir Gemayel’s death. By their own peculiar lights who could blame them? Not in their wildest dreams could they have imagined things going so smoothly. Now, logically, they joined the Palestinians and the Lebanese Moslems in the losers’ circle they so steadfastly had fought to avoid over the years. For with Gemayel’s death they had lost their best chance of reimposing their hegemony on Lebanon’s Moslem majority, their undeclared goal during more than seven years of fighting and scheming.

Impenitent gamblers that they are, the militant Christians of Lebanon, especially the many Maronites who form their core, had played and lost time and again, then doubled the stakes; never listening for long to moderate counsel, supping with dangerous foreign allies they privately derided as little better than devils, they never, never abandoned hope. They were the despair of the other Lebanese, including their less extremist co-religionists. The militant Christians had signed the 1969 Cairo accords legitimizing the Palestine Liberation Organization’s pretensions to being a state-within-a-state. Then they had moved heaven and earth to bring in the Syrian Army to save them from the Palestinians in 1976. And they had concluded a de facto alliance with Israel—long before Egyptian President Anwar Sadat embarked on his fatal adventure with the Jewish state. King Abdullah of Transjordan in 1951, Sadat in 1981, and now Bashir Gemayel—all the Arab leaders who dared to deal openly with Israel ended up assassinated.

Yet all during the summer of 1982, from the narrow confines of their ghetto outlook, the militant Christians witnessed not just one miracle but a series of miracles.

First Israel unleashed its terrible swift sword at long last, smiting the dreaded Syrians and the hated Palestinians rather than just playing them off against each other and preserving the despised status quo. Lebanon for the Lebanese, the Christian leaders had said all along, and now that it was happening they intended to make sure it would be a Christian-run Lebanon. The best part was that it was not even the Christian militia’s war: Israel was doing the fighting, but the Christians stood to share the fruits of victory whether or not they took an active part. The Israelis were openly resentful of their “chocolate soldier” allies for failing to honor their word and join the fighting. But Bashir Gemayel repeatedly denied he had made any such undertaking. Israel, he hinted, should be content with the rear-base facilities it had in the Christian ghetto of Beirut and the alliance with the Lebanese Forces that had served as the intellectual foundation justifying the invasion.

It was the Lebanese Forces’ decision not to fight alongside the Israelis that helped win over a suspicious United States government to Gemayel’s presidential ambitions. The Americans feared that any Christian militia’s participation in the fighting would split Lebanon, perhaps for good, and make reconciliation with the country’s Moslem majority all but impossible. Despite the massive Israeli destruction visited upon the mostly Moslem sectors of West Beirut, which left most Christians unmoved and ensured the opposition of the mainstream Moslem leadership to Bashir Gemayel, he won the presidency, traditionally reserved for one of his sect. His was a campaign combining muscle, money, and persuasion so convincingly that no other Maronite Christian dared run against him for the land’s highest office.

More miraculous yet, the United States government did nothing to stop the Israelis, either in the first two days of the invasion in south Lebanon, or once the invaders swept north and encircled half a million West Beirutis along with the PLO leadership. For Gemayel the American forbearance marked an extraordinary change of heart. Both during the 1978 Israeli invasion of south Lebanon and again in 1981, during the battle of Zahle and the ensuing missile crisis in the Beqaa valley, the United States had moved forcefully to stop the Israelis. Now, under Secretary of State Alexander M. Haig, Jr., the Reagan administration gave every indication of letting events—Israeli-dictated events—take their course. The Lebanese Christians had doubted this briefly, in late June, when Haig resigned—in part because of the controversy that his Lebanese policy caused. But then the United States dispatched Marines abroad in battle formation to supervise the departure of the PLO leadership. By late August, Marines were in Beirut. Whatever the consequences for the other participants in the conflict, the Lebanese Forces convinced themselves that the Americans had finally come around to their way of seeing things. In the past, the United States had allowed Lebanon to remain a sideshow of the Middle East, a killing ground where all the regional powers vented their aggressions. Now the United States, they kept persuading themselves, was willing to find a separate solution to Lebanon’s travail, rather than subordinating its fate to an overall Middle East settlement

Estranged for years from successive American administrations, all of which had mistrusted the muscular Christians’ scheming to involve the United States against its will in major policy changes in the Middle East, Gemayel was not that unhappy with the frictions between Washington and Jerusalem provoked by the summer war of 1982. For him, Israel had always been second best, an ersatz Western power and only an alternative when the Christians’ traditional Western friends refused to follow them down their path of death and destruction. The world’s number-one nation was a more attractive ally than the Middle East’s superpower. The United States was immeasurably more acceptable to the Arab world and conveniently separated from it by thousands of miles of ocean. It was not a dangerously meddlesome neighbor. If Israel now opted for a weak Lebanon, partitioned between itself and Syria, in preference to its publicly stated support for a strong central government in Lebanon, then the United States could be counted on to fight the battle for the Christians. Or so the muscular Christians argued, jubilant at what they considered their windfall backing from the United States. They were convinced they could play the Americans off against the Israelis for their own greater glory. Some Gemayel lieutenants even talked of turning their overarmed country into a neutral state, the Switzerland of the Middle East that the tourist brochures had so inaccurately touted before things fell apart in 1975.

But these two miracles paled in comparison with the third.

Only weeks after his election, and nine days before he was due to take office for a six-year term, Gemayel was well on his way to winning over a largely suspicious nation, especially its Moslems. In part this success was due to a newfound willingness to say the politic thing: reunification, reconciliation, turning the page, homage to his old enemies’ dead, guaranteeing press freedom—promises dictated not only by common sense but by his insistent American protectors. The tough, ruthless, impulsive warlord, so often depicted as a bloodthirsty, mono-maniacal defender of muscular Christianity, the bogeyman with whom many a Moslem mother threatened her disobedient child, was now transmogrified into President of all the Lebanese. And what a task that was—uniting three million members of sixteen officially recognized sects living in a country the size of Connecticut, at times held together only in their paranoid fear and loathing of each other. If the civil servants were any yardstick, he’ might just succeed. For years either absent or surly, always corrupt and unhelpful, now suddenly they were at their offices all day long, protesting feigned shock at the bribes preferred by the populace as the routine price of doing business. “Sheikh Bashir would hang me by my thumbs,” said a frightened repairman when I pulled out money to speed the repair of my telephone, which in the past regularly went on the blink to round out his wages.

Completing Gemayel’s new, post-election image was a suggestion of his nascent independence from the Israelis to whom he owed so much. As far as can be ascertained, he did nothing more to shed his quisling clothes than discourage Israel’s insistent demands for an immediate peace treaty with Lebanon. A treaty was sure to create even greater Christian-Moslem tensions inside Lebanon and to threaten it with a humbling Arab economic boycott. The endless violence had destroyed so much of Lebanon’s economic infrastructure—and discouraged so many Lebanese—that hundreds of thousands had sought security and employment in the conservative oil nations of the Persian Gulf; their remittances kept the Lebanese economy afloat. And Arab oil money could rebuild the damage sustained in the war, much of it caused by the Israeli invaders.

Nonetheless, Menachem Begin adamantly insisted on the treaty, which he saw as a companion accomplishment to the one he had signed with Egypt. For years, he had regularly accompanied often unprovoked Israeli air or land raids against Lebanon by pious proposals that he meet with President Elias Sarkis to sign such a treaty, repeatedly deemed the sovereign cure for bilateral Israeli-Lebanese problems. In the past such gestures had been dismissed in Lebanon as further manifestations of Begin’s inability or unwillingness to understand the country’s suffering, an Israeli joke in the worst possible taste. Gemayel came to realize the dangers of a peace treaty with Israel—at least before an overall Middle East settlement was achieved—despite that old saw of some thirty years’ standing that insisted that Lebanon would be the second Arab state to do so. During the summer of 1982, even the state-owned Israeli Radio acknowledged that Begin was faced with a straight choice: a strong Lebanese central government friendly to Israel or a peace treaty; he could not have both. Gemayel’s hesitation to agree to Begin’s demands pleased many wary Christians and Moslems in Lebanon. Coming from a man widely suspected of abject fealty to Israel, any show of independence was seized upon as evidence that he was coming to understand the constraints of national office. It bespoke common sense—and Western, especially American, influence, which was judged more evenhanded and disinterested than Israel’s.

In any event, Gemayel was caught in the emerging test of wills between the United States and Israel, which flattered his sense of self-importance. He had felt at home enough with the Israelis to have bought three hundred sixty military trucks from Automotiv Industries of Israel, which began delivery just before the war. He dined openly with Ariel Sharon during the Israeli Defense Minister’s Beirut visits. And American senators and other officials now started popping up regularly. But on September 1 President Reagan gave a speech advocating a freeze of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza Strip pending a solution for those Israeli-occupied territories, and the tensions between Washington and Jerusalem immediately increased. Two days later, Israeli troops conspicuously violated their undertakings to the United States and advanced 600 yards into West Beirut to positions overlooking the P...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface to the 2012 Edition

- Preface to the 1983 Edition

- 1. Miracles and Hallucinations

- 2. Does the Rooster Know?

- 3. Things Fall Apart

- 4. The Irresistible Ascension of Bashir Gemayel

- 5. The Offhand Americans

- 6. The Israeli Connection

- 7. All Fall down

- 8. November 1983